|

History of the Old

Almanach de Gotha Original Royal Genealogical Reference Handbook

Genuine Editions - 1763-1944

The Almanach de Gotha book would enter the language

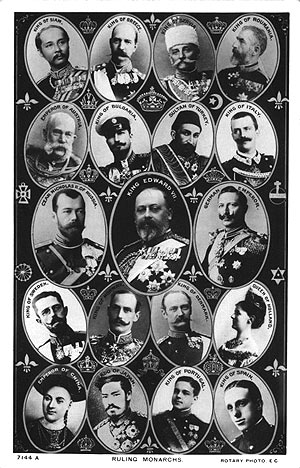

in its own right with the words 'all the Gotha was there'. Historically the Gotha has listed the Ruling Imperial, Royal

and Princely Families of Europe, finally coming to an end with the Soviet occupation of the former Saxon Duchy of Saxe-Coburg und Gotha in the Year 1944 after nearly 181 years of European Royal Genealogical

Reference.  The Almanach provided detailed facts and statistics

on nations of the world, including their reigning and formerly reigning houses, those of Europe being more complete than those

of other continents. It also named the highest incumbent officers of state, members of the diplomatic corps, and Europe's

upper nobility with their families. Although at its most extensive the Almanach de Gotha numbered more than 1200 pages, fewer

than half of which were dedicated to monarchical or aristocratic data, it acquired a reputation for the breadth and precision

of its information on royalty and nobility compared to other Almanach's. It was Emmanuel Christoph Klupfel (1712-76) being chaplain

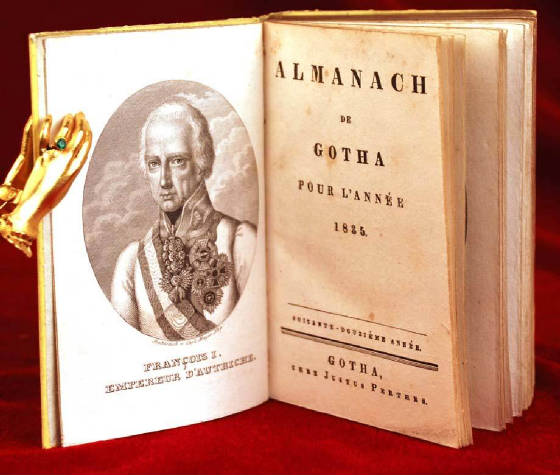

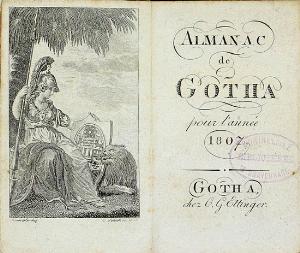

and later tutor to the young hereditary Prince of Saxe-Coburg, who was the founder of the Almanach de Gotha. The Almanach de Gotha published by Justus Perthes made its debut

in the German Duchy of Saxe-Coburg und Gotha in 1763, the Court which during the 1760's under Duke

Friedrich III and later under Duke Ernest II attracted Voltaire and which in the mid 1800's produced Prince Albert as consort

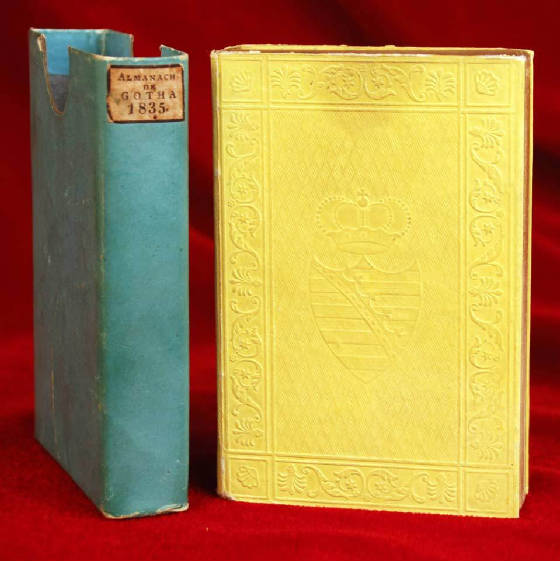

for Queen Victoria. The Gotha's own familiar crown was stamped on the cover of what was to become the ultimate power register

of the ruling classes.  The Almanach de Gotha was unmoved by government

decrees or bribes, those not included in its pages found themselves thwarted, Pretenders claims left in ruins, by the publisher

who would not compromise itself for either inclusion or exclusion. Napoleon's reaction was typical. On 20 October 1807 the

Emperor wrote to his Foreign Minister, de Champagny: 'Monsieur de Champagny, this year's Almanach de Gotha is badly done.

I protest. There should be more of the French Nobility I have created and less of the German Princes who are no longer sovereign.

Furthermore, the Imperial Family of Bonaparte should appear before all other royal dynasties, and let it be clear that we

and not the Bourbons are the House of France. Summon the Minister of the Interior of Gotha at once so that I personally may

order these changes'.

The

Almanach de Gotha simply produced two editions the following year, the first the extremely rare "Edition for France -

at His Imperial Majesty's Request" and the other "The Gotha - Correct in All Detail" Historically the Gotha

was the determining instrument when it came to matters of protocol. Not only were orders of precedence easily checked, but

marriages between parties not listed in the same Gotha section were often considered unequal at some courts, participants

thereby loosing dynastic privileges and sometimes title and rank. The term morganatic applied to the marriage; it derived

from the High German morgangeba, a gift by a groom to his bride on the morning following their wedding. It indicated that

this was the full and only entitlement that the wife could expect from her new husband. Morganatic marriages were often called

'left hand marriages' due to the fact that inequality in rank required the groom to use his left hand instead or the right

during the wedding ceremony.  Concerning listing within the Gotha, the Ducal House of Saxe-Coburg

was listed first therein well into the 19th century, usually followed by kindred sovereigns of the House of Wettin and then,

in alphabetical order, other families of princely rank, ruling and non-ruling. Although always published in French, other

almanacs in French and English were more widely sold internationally. The almanac's structure changed and its scope expanded

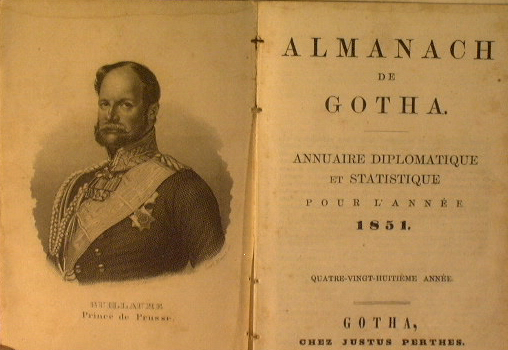

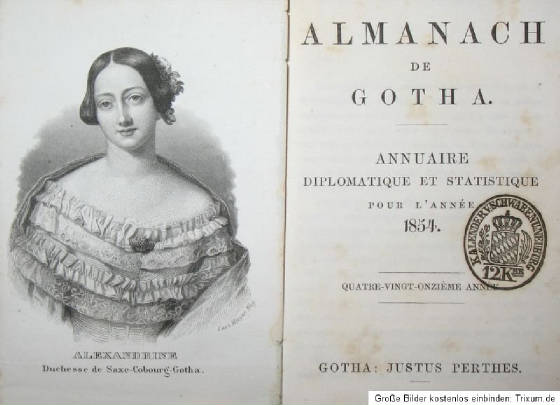

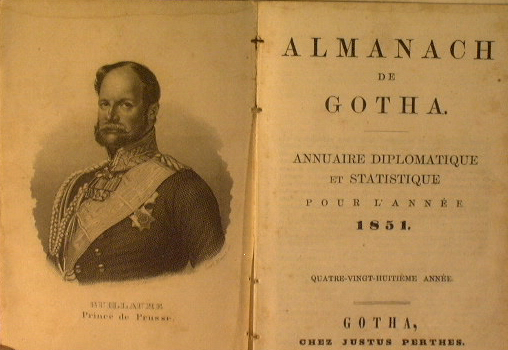

over the years. The second portion, called the Annuaire diplomatique et statistique ("Diplomatic and Statistical Yearbook"),

provided demographic and governmental information by nation, similar to other Almanach's. Its first portion, called the Annuaire

Genealogique ("Genealogical Yearbook"), came to consist essentially of three sections: reigning and formerly reigning

families, mediatized families and non-sovereign families at least one of whose members bore the title of prince or duke.  The first section always listed Europe's sovereign houses,

whether they ruled as emperor, king, grand duke, duke, prince (or some other title, e.g., prince elector, margrave, landgrave,

count palatine or pope). Until 1810 these sovereign houses were listed alongside such families and entities as Barbiano-Belgiojoso,

Clary, Colloredo, Furstenberg, the Emperor, Genoa, Gonzaga, Hatzfeld, Jablonowski, Kinsky, Ligne, the Order of Malta, Paar,

Radziwill, Starhemberg, Thurn and Taxis, Turkey, Venice and the Order of Malta and the Teutonic Knights. In 1812, these entries

began to be listed in groups. First, were German sovereigns who held the rank of grand duke or prince elector and above (the

Duke of Saxe-Gotha was, however, listed here along with, but before, France.  Listed next were Germany's reigning ducal and princely dynasties

under the heading "College of Princes", e.g., Hohenzollern, Isenburg, Leyen, Liechtenstein and the other Saxon duchies.

They were followed by heads of non-German monarchies, i.e. Austria, Brazil, Great Britain, etc. Fourthly were listed non-reigning

dukes and princes, whether mediatized or not, including Arenberg, Croy, Furstenberg alongside Batthyany, Jablonowski, Sulkowski,

Porcia, and Benevento. In 1841 a third group was added

to those of the sovereign dynasties and the non-reigning princely and ducal families. It was comprised exclusively of the

mediatized families of countly rank recognized as belonging, since 1825, to the same historical category and sharing some

of the same privileges as reigning dynasties by the various states of the German Confederation; these families were German

with a few exceptions (e.g. Bentinck, Rechteren-Limpurg). The 1815 treaty of the Congress of Vienna had authorized and Article

14 of the German Confederation's Bundesakt (charter) recognized retention from the German Imperial regime of equality of birth

for marital purposes of mediatized families (called Standesherren) to reigning dynasties. The Almanach added a third section

consisting exclusively of mediatized famiies of countly rank.  In 1877, the mediatized countly families of the Holy Roman

Empire were moved from section III to section II A, where

they joined the princely mediatized families of Europe. For the first time in the century of its existence, the largely non-German,

un-mediatized princely and ducal families of the Almanach de Gotha were removed from the same section as other non-reigning

families bearing princely titles. While non-mediatized German and Austrian families (e.g. Lichnowsky, Wrede), were likewise

relocated from the almanac's second to its third section, the second section's new preponderance of German families, princely

and countly, which were henceforth recognized as possessing the exclusive privilege of inter-marriage with reigning dynasties

was salient. Excluded were members of such historically notable Princely and Ducal families as the Rohans, Orsinis, Ursels,

Norfolks, Czartoryskis, Galitzines, La Rochefoucaulds, Kinskys, Radziwills, Merodes, Dohnas and Albas.   Although theoretically mediatized families were distinguished

from Europe's other nobility by the former status of their territories as Reichsstand and their exercise within the Holy Roman

Empire of "semi-sovereignty" or imperial immediacy (Reichsunmittelbarkeit), many Standesherr families, especially

those bearing the comital title, had not been fully recognized as legally possessing immediate status within the Empire prior

to its collapse in 1806. No other families whose highest title was count were admitted to any section of the Gotha Almanach.  Some dynastic house laws in existence today continue to exclude members who marry a spouse from outside

the Gotha Part One or Part Two families. Dynasts loose all rights and refrain from the adoption of ancestral titles. In some

German families this can still mean forfeiture of estates and property. However in a number of recent cases, marriages have

been contracted which clearly fall well beyond the scope of what could be described as equal, but the head of the family at

the time has been able to rely on obscure sub-clauses of family law which allows discretionary permission for such marriages

to take place within the set family house law concerned.  Listings

are now in genealogical order and the issue of morganatic marriages and the marriages themselves are now listed in the main

body of the family entry from which they derive. There are sensible reasons for this. Previously when many more families were

reigning new titles were created and a listing under a new line, in Part Three, placed the new generation according to rank.

It was decided, however, after careful deliberation, that the Gotha should now retain family entries intact where they continue

using the same name. However where an individual has renounced his rights or becomes a non-dynast as a result, we have marked

this fact against the entry where it is the wish of the head of the family that we do so. In this way dynastic breaches are

still clearly distinguished. Historically there has been a divergence of opinion on the question of morganatic marriages.

Whilst some families believed the matter to be an issue of sacred proportions, others, such as Queen Victoria regarded it

as ridiculous. Only on one occasion in Britain did the question arise, uniquely the letters patent issued

on the creation of the Dukedom of Windsor provided for the rank and style of Royal Highness for the Duke alone and not his

wife or any subsequent issue. But that itself followed the earlier constitutional ruling by Prime Minister Baldwin, on the

advice of lawyers, who were clear that the wife of a King was the Queen. Whereas It is understandable why, previously a sustained

and concerted effort has been made by a caste to preserve and enhance its own status by means of a highly complex an obscure

set of rules. This did of course occasionally lead to confusion.

The

late Princess Alice of Albany, Countess of Athlone once recounted that at formal receptions at the Imperial German Court

in Berlin, that Royal Highnesses were shepherded by the Court Chamberlains into a room by themselves and were presented to

the Kaiser and Kaiserin of Germany before the other European Royals. Princess Alice recalled that her cousin Princess Pauline of Wurttemberg, was so furious

at being separated from her beloved husband the Prince of Wied that she never returned to the Imperial Court of Germany, whereas

Princess Alice by contrast, the daughter of one of Queen Victoria's sons Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany, but married

to HSH Prince Alexander of Teck who was the fourth child and third son of Prince Francis, Duke of Teck, and Princess Mary,

Duchess of Teck, found the situation quite hilarious.  World

War Two finally ended in 1945, the Soviets went on to occupy the old Duchy of Gotha they immediately stormed the factory where

the presses were housed and within five short days, in a public display of protest, destroyed, by burning, most of the Imperial

and Royal genealogical and heraldic archives, since the books contained detailed references to many Royal Houses of

Europe which included the Romanov Dynasty former Imperial House of Russia, the attempt to obliterate history was made against

these milestones, the fate of the entire archive still remains somewhat of a mystery, what was to the Soviets a classic symbol

of a degenerate bourgeois European society, was in any case a substantial archive of Genealogy on European Royalty and Nobility,

over 100,000 maps and 80,000 books survived and the remaining assets in Gotha were returned after reunification of Germany,

whereas the genuine 'Gotha' has not been re-published or re-issued since 1944 being the date of its last genuine edition as

stated by the family of Justus Perthes.

New London publication - 1998 In 1989 the family of Justus Perthes re-established its right to the use of the name Almanach

de Gotha, the family then sold these rights to a new company called Almanach de Gotha Limited which was formed in London.

Justus Perthes considers this a new work and not a continuation of the series last published by the family in 1944 with the

181st and last genuine edition. The new publishers launched with their 1st edition on 16th of March 1998 at Claridge's Hotel

in London, it was written in English instead of French as the Editor felt that English was now the language of diplomacy.

A review in the Economist magazine criticised the London based

edition for its low editorial standards and attacked Volume II for a purported lack of genealogical accuracy, the full artical

can be viewed below for reference. Whereas it should be noted that the London based Almanach de Gotha Limited has no connection

to Justus Perthes other than the purchase of rights to use the Almanach de Gotha name under licence and as such their publication

can not and should not be considered either a continuation of the Old Gotha or in fact a Original copy of the legendary Almanach

de Gotha of the same name. An

interesting artical concerning the present status of the company Almanach de Gotha Ltd and their website's being: www.gotha1763.com

and www.almanachdegotha.com, can be viewed on the website: Real Titles and Orders, which have written an artical on the present

status of the Original Almanach

de Gotha, please see the following weblink named: The Almanach de Gotha Ltd and their website www.gotha1763.com are not the original Almanach de Gotha

Gothic Horror New London Almanach

de Gotha - Volume II Dated:

Jan 24th 2002 FROM

1763 until the Russians stopped the presses when they swept into eastern Germany towards the end of the second world war,

the Almanach de Gotha published elaborate lists and potted genealogies of Europe's royal, semi-royal and leading ducal families.

It was relaunched in 1998-a cause for music-hall jollity, if not historical excitement. Once again snobs and sneerers alike

could work out where the Kotchoubeys de Beauharnais, the Barbianos di Belgiojoso d'Este and the Batthyany Strattmanns now

live, whom they have married, what they do, and even-reading between the blood lines-whether they still, ahem, count. The sine qua non of any reference book, however

frivolous, is accuracy. Unfortunately, the latest instalment of the Almanach, which purports to document those families that

aren't quite royal but are still pretty grand, is perhaps the most laughably sloppy product of its kind ever to have been

published. It used, in the old days, to be in French. Now it is in English, albeit the English of someone apparently in desperate

need of both a dictionary and a spell-check function on his PC. The book's very first page, addressing the Hamiltons of Abercorn,

Ulster's only ducal family, contains no fewer than six howlers, starting on the third line, where a lymphad (a Viking ship

common in west-coast Scottish coats of arms) becomes a "hymphad". Bloopers and typos abound: "moddel", "marshall", "sollicitor",

"baronett", "the Scotts Guards", "the Royal Human Society". Translations are quirky: try "annulated"

for annulled, or "secret camerist" for chamberlain. Place-names are particularly wayward: witness "Marocco",

"Varsaw", "Turquey" and "Tchechoslovaquia". The editor even manages to place the principality

of Liechtenstein (misspelt, of course, without its first "e") in Germany. If the Almanach's genealogical accuracy is of a similar standard,

the matchmaking dowagers perusing its pages had better watch out. Their eyebrows might in any event twitch if they were to

read on the Almanach's website that its editor, John Kennedy, was "a former member of the [British] royal household"

who is "separated from his partner, Princess Lavinia of Yugoslavia". Eh? Mr Kennedy, formerly Jovan Gvozdenovic,

is a sometime Conservative candidate for parliament who lobbied for Radovan Karadzic and once worked for Prince Michael of

Kent. Presumably he dated the lovely Lav, herself born out of wedlock to a Karageorgevic. Gosh! But if you go by the number of families still carrying royal-sounding

prefixes, it is the Germans, of course, who provide Europe, and the Almanach, with its princely ballast, thanks mostly to

the Holy Roman Empire. Some 16 German families, excluding the Habsburgs and the Liechtensteins, are deemed top-flight royalty

by virtue of being more or less sovereign at some relatively recent historical moment, and are therefore included in the first

volume. Among them is the family of Reuss, all of whose males are, confusingly enough, called Heinrich, 35 of whom were born

in the last century. The

second part of volume one catalogues "mediatised princely families": those which at some early point became subordinate

to a greater royal house. There are 47 such families, whose members all call themselves princes and princesses. They have,

it seems, survived quite well. They still overwhelmingly marry within caste; many still live in the ancestral schloss; they

still have some cash; but few play much part in public life or politics. It is in the second and newest volume that one enters a realm of fully-fledged absurdity.

The choice of families is largely arbitrary. Only seven of Britain's 24 non-royal dukedoms are chronicled, and those very

patchily; most of the others are merely mentioned in the contents pages, while three of the grandest, Norfolk, Beaufort and

Northumberland, are ignored altogether. Of Europe's 274 non-royal but princely or ducal families considered worthy of entry,

about a hundred listed in the contents pages are then bizarrely revealed to be extinct or documented only in previous, pre-1944

editions. It is an almanac with a most random kind of calendar. How grand is a prince? In terms of commonness, Italian princeliness is the most devalued.

Some 84 Italian families pop into the book, about a sixth of them Sicilian. (This represents a considerable drop from earlier,

more vainglorious times: in 1800 Sicily alone boasted more than 100 princely and ducal families.) The French come next, with

about 40 families chosen, a quarter of which flaunt dukedoms of mostly martial Bonapartist creation (Berthier, Davout, Junot,

MacMahon, Murat and Ney among them); roughly half of the rest are post-Revolutionary creations. The Germans are still doing

well, with another 29 third-division princely families listed, to add to the 63 in the first volume. A good many Russian and

Polish families are given princely documentation, though once again with some glaring omissions. To put it kindly, there are princes and princes. At a guess, there

are probably more than 2,000 German ones-three times the number of hereditary British peers. Britain's royal house has fewer

than a score of living princes and princesses. To the unwary Almanach-reader, they would appear to be outshone by the family

of Beguin Billecocq Durazzo, who have a full score of members bearing a seemingly royal prefix. No matter that their title

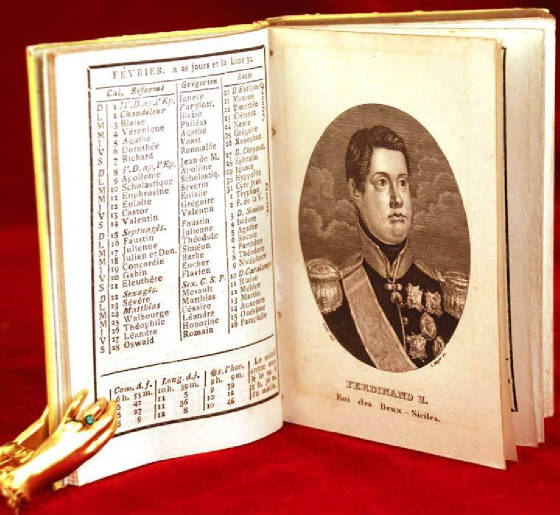

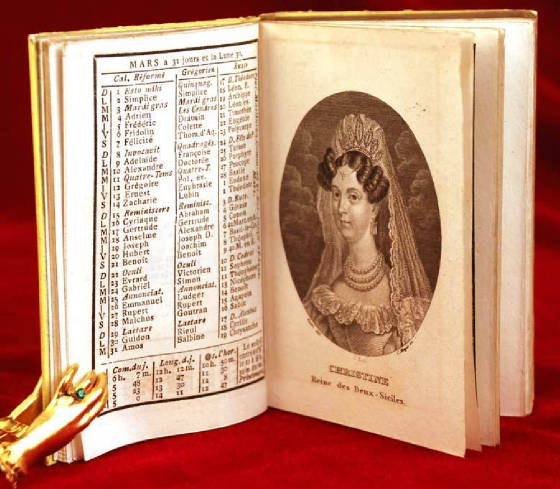

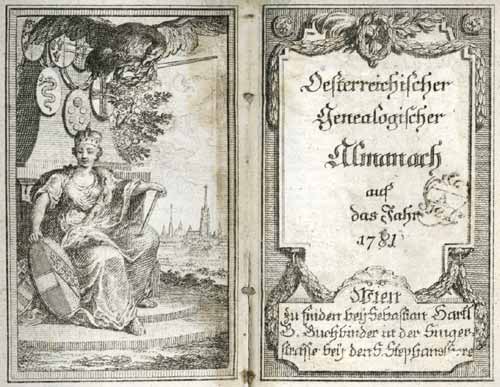

was acquired in 1929 from Albania's King Zog when grandpa was an insignificant French ambassador.  Old Almanach

de Gotha Bookplates

Gallery of Bookplates

|