|

The Emperor of China (Chinese: 皇帝;

pinyin: Huángdì, pronounced [xu̯ɑ̌ŋ tɨ̂]) refers to any sovereign of Imperial

China reigning between the founding of Qin Dynasty of China, united by the King of Qin in 221 BCE, and the fall of Yuan Shikai's

Empire of China in 1916. When referred to as the Son of Heaven (Chinese: 天子; pinyin: tiānzǐ, pronounced

[ti̯ɛ́n tsɨ̀]), a title that predates the Qin unification, the Emperor was recognized as the ruler

of "All under heaven" (i.e., the world). In practice not every Emperor held supreme power, though this was most

often the case.  Emperors from the same family are generally classified in

historical periods known as Dynasties. Most of China's imperial rulers have commonly been considered members of the Han ethnicity,

although recent scholarship tends to be wary of applying current ethnic categories to historical situations. During the Yuan

and Qing dynasties China was ruled by ethnic Mongols and Manchus respectively after being conquered by them. The orthodox

historical view over the years sees these as non-native dynasties that were sinicized over time, though some more recent scholars

argue that the interaction between politics and ethnicity was far more complex. Nevertheless, in both cases these rulers had

claimed the Mandate of Heaven to assume the role of traditional emperors in order to rule over China proper. Origin and History of the Chinese Emperor Chinese feudal rulers with

power over their particular fiefdoms were called Wang (王), roughly translated as King, but in fact somewhat amorphous

and also readily maps to "duke" in English. In 221 BCE, after the then King of Qin completed the conquest of the

various kingdoms/duchies of the Warring States Period, he adopted a new title to reflect his prestige as a ruler greater than

the rulers before him. He created the new title Huangdi or "Emperor", and styled himself Shi Huangdi, the First

Emperor. Before this, Huang (皇) and Di (帝) were given as titles of a number of rulers from the era known as

the "sage kings" period, supposedly predating written history, but probably coinciding with or following the invention

and early stages of evolution for the Chinese writing system. Huang (皇) was the title generally used for divine entities

and legendary/deified rulers, and Di (帝) was used for feudal rulers of vassals who were themselves rulers of their

own principalities.

Though

these words came to be used synonymously and interchangeably, at the time of Ying Zheng's rule, they were not used together,

and would have carried the connotation of "The Holy Emperor" because Huang (皇) was previously associated

with divine or deified entities. Furthermore, it is generally agreed upon that the founding of the dominant Chinese race,

the Han 漢 race, was the result of the "Yellow Emperor" Huangdi 黃帝, who unified a federation

of tribes to drive the other tribes out of central China as it was known then (today's northwestern China), and several imperial

dynasties existed since the time of Huang Di and before the time of Ying Zheng, the last of which integral dynasties, the

Zhou 周 dynasty, disintegrated and formed the "Warring Nations" which were principalities of various sizes

roughly based on the feudal kingdoms and duchies as ascribed under the Zhou dynasty political system.[citation needed] Ying

Zheng, therefore, should really be called the re-unifier of the Chinese empire after the fall of the Zhou Dynasty, and his

title should more correctly be rendered as "The First Holy Emperor" as opposed to the much less nuanced (and in

fact much less accurate) "First Emperor." This is further evidenced by the fact that Chinese emperors since Ying

Zheng also typically took on the title 帝 rather than 皇帝, e.g. Han Wu Di 漢武帝 "Emperor

Wu of Han [Dynasty]", and it was not until much later that the term Huang Di 皇帝 came to be used interchangeably

with the shorter Di 帝.

There

is one minor exception to this interpretation in that, where the father of he who has ascended to the throne as emperor of

China is still alive, this progenitor of the present emperor would be given the title Tai shang huang 太上皇,

literally the "The Grand/Over-Emperor" or the "Grand Imperial Sire" or in the context of "Holy Emperor",

the "Holy Imperial Sire." It is said that this practice was initiated by Liu Bang 劉邦, the founder

of the Han Dynasty, in emulation of Ying Zheng (who granted his own father the title posthumously once he took on the new

title of Huangdi 皇帝 for himself), because Liu Bang would not be bowed to by his own father, who was still technically

a commoner. Chinese political theory does not totally discourage or prevent the rule of non-royals or foreigners holding the

title of "Emperor of China". Historically, China has been divided, numerous times, into smaller kingdoms under separate

rulers or warlords. The Emperor in most cases was the ruler of a united China, or must at least have claimed legitimate rule

over all of China if he did not have de facto control. There have been a number of instances where there has been more than

one "Emperor of All China" simultaneously in Chinese history. For example, various Ming Dynasty princes continued

to claim the title after the founding of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), and Wu Sangui claimed the title during the Kangxi Emperor's

reign. In dynasties founded by foreign conquering tribes that eventually became immersed in Chinese culture, politics, and

society, the rulers would adopt the title of Emperor of China in addition to whatever titles they may have had from their

original homeland. Thus, Kublai Khan was simultaneously Khagan of the Mongols and Emperor of China  Number of Emperors of China From the Qin Dynasty to the

Qing Dynasty, there were 557 Emperors (including rules of minor states). Some, such as Li Zicheng and Yuan Shu, declared themselves

emperors and founded their own empires as a rival government to challenge the legitimacy of the existing emperor. Among the

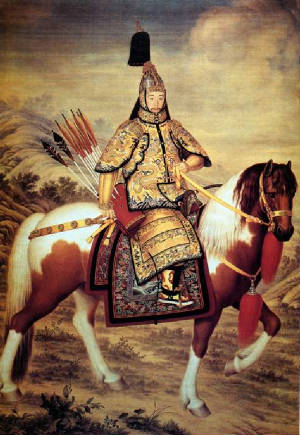

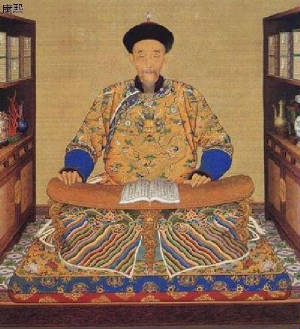

most famous Emperors are Qin Shi Huang of the Qin Dynasty, Emperors Gaozu and Wu of the Han Dynasty, Emperor Taizong of the

Tang Dynasty, Kublai Khan of the Yuan Dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming Dynasty and the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing Dynasty. The emperor's words were

considered sacred edicts (聖旨), and his written proclamations "directives from above" (上諭).

In theory, the emperor's orders were to be obeyed immediately. He was elevated above all commoners, nobility and members of

the imperial family. Addresses to the emperor were always to be formal and self-deprecatory, even by the closest of family

members.

In practice, however, the power of the emperor varied between different emperors and different dynasties.

Generally, in the Chinese dynastic cycle, Emperors founding a dynasty usually consolidated the empire through absolute rule,

examples including Shi Huang of the Qin Dynasty, Taizong of the Tang Dynasty, Kublai Khan of the Yuan Dynasty, and Kangxi

of the Qing Dynasty. These emperors ruled as absolute monarchs throughout their reign, maintaining a centralized grip on the

country. During the Song Dynasty, the Emperor's power was significantly overshadowed by the power of the chancellor.

The Emperor's

position, unless deposed in a rebellion, was always hereditary, usually by agnatic primogeniture. As a result, many Emperors

ascended the throne while still children. During these minorities, the Empress Dowager (i.e., the Emperor's mother) would

possess significant power. In fact, the vast majority of female rulers throughout Chinese Imperial history came to power by

ruling as regents on behalf of their sons; prominent examples include the Empress Lü of the Han Dynasty, as well as Empress

Dowager Cixi and Empress Dowager Ci'an of the Qing Dynasty, who for a time ruled jointly as co-regents. Where Empresses Dowager

were too weak to assume power, court officials often seized control. Court eunuchs had a significant role in the power structure,

as Emperors often relied on a few of them as confidants, which gave them access to many court documents. In a few places,

eunuchs wielded vast power; one of the most powerful eunuchs in Chinese history was Wei Zhongxian during the Ming Dynasty.

Occasionally, other nobles seized power as regents. The actual area ruled by the Emperor of China varied from dynasty to dynasty.

In some cases, such as during the Southern Song dynasty, political power in East Asia was effectively split among several

governments; nonetheless, the political fiction that there was but one ruler was maintained.  Imperial Succession of Emperor The title of emperor was hereditary, traditionally passed on from father to son in each

dynasty. There are also instances where the throne is assumed by a younger brother, should the deceased Emperor have no male

offspring. By convention in most dynasties, the eldest son born to the Empress (嫡長子) succeeded to the

throne. In some cases when the empress did not bear any children, the emperor would have a child with another of his many

wives (all children of the emperor were said also to be the children of the empress, regardless of birth mother). In some

dynasties the succession of the empress' eldest son was disputed, and because many emperors had large numbers of progeny,

there were wars of succession between rival sons. In an attempt to resolve after-death disputes, the emperor, while still

living, often designated a Crown Prince (太子). Even such a clear designation, however, was often thwarted by

jealousy and distrust, whether it was the crown prince plotting against the emperor, or brothers plotting against each other.

Some emperors, like the Kangxi Emperor, after abolishing the position of Crown Prince, placed the succession papers in a sealed

box, only to be opened and announced after his death.  Unlike, for example, the Japanese monarchy, Chinese political

theory allowed for a change in the ruling house. This was based on the concept of the "Mandate of Heaven". The theory

behind this was that the Chinese emperor acted as the "Son of Heaven" and held a mandate to rule over everyone else

in the world; but only as long as he served the people well. If the quality of rule became questionable because of repeated

natural disasters such as flood or famine, or for other reasons, then rebellion was justified. This important concept legitimized

the dynastic cycle or the change of dynasties. This principle made it possible

even for peasants to found new dynasties, as happened with the Han and Ming dynasties, and for the establishment of conquest

dynasties such as the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty and Manchu-led Qing Dynasty. It was moral integrity and benevolent leadership

that determined the holder of the "Mandate of Heaven". There has been only one lawful reigning Empress in China,

Empress Wu of the Tang dynasty or the Wu-Zhou (Wu-Chou) dynasty founded by her. Many females, however, did become de facto

leaders, usually as Empress Dowager. Prominent examples include Empress Dowager Cixi, mother of the Tongzhi Emperor (1861-1874),

and aunt and adoptive mother of the Guangxu Emperor (1874-1908), who ruled China for 47 years (1861-1908), Empress Wu Zetian

(who ultimately declared herself Empress, and was subsequently overthrown) and the Empress Dowager Lü of the Han Dynasty. Titles, Styles, and Appellations of the Emperor As the emperor

had, by law, an absolute position not to be challenged by anyone else, his subjects were to show the utmost respect in his

presence, whether in direct conversation or otherwise. When approaching the Imperial throne, one was expected to kowtow before

the Emperor. In a conversation with the emperor, it was considered a crime to compare oneself to the emperor in any way. It

was taboo to refer to the emperor by his given name, even if it came from his own mother, who instead was to use Huangdi (Emperor),

or simply Er ("son"). The emperor was never to be addressed as you. Anyone who spoke to the emperor was to address

him as Bixia (陛下), corresponding to "Your Imperial Majesty", Huang Shang (皇上, lit. Emperor

Above or Emperor Highness), Tian zi (天子, lit. the Son of Heaven ), or Sheng Shang (聖上, lit. the

Divine Above or the Holy Highness). The emperor

could also be alluded to indirectly through reference to the imperial dragon symbology. Servants often addressed the emperor

as Wan Sui Ye (萬歲爺, lit. Lord of Ten thousand years). The emperor referred to himself as Zhen (朕),

translated into the royal "We", in front of his subjects, a practice reserved solely for the emperor.In

contrast to the Western convention of referring to a sovereign using a regnal name (e.g. George V) or by a personal name (e.g.

Queen Victoria), a governing emperor was to be referred to simply as Huangdi Bixia (皇帝陛下, His

Majesty the Emperor) or Dangjin Huangshang (當今皇上, The Imperial Highness of the Present Time) when

spoken about in the third person. He was usually styled His Imperial Majesty the Emperor of the Great [X] Dynasty, Son of

Heaven, Lord of Ten Thousand Years. Forms of address varied considerably during the Yuan and Qing Dynasties. Generally, emperors also

ruled with an era name (年號). Since the adoption of era name by Emperor Wu of Han and up until the Ming Dynasty,

the sovereign conventionally changed the era name on a semi-regular basis during his reign. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties,

emperors simply chose one era name for their entire reign, and people often referred to past emperors with that title. In

earlier dynasties, the emperors were known with a temple name (廟號) given after their death. All emperors were

also given a posthumous name (謚號), which was sometimes combined with the temple name (e.g. Emperor Shengzuren

聖祖仁皇帝 for Kangxi). The passing of an emperor was referred to as jiabeng (駕崩,

lit. "collapse of the [imperial] chariot") and an emperor that had just died was referred to as Daxing Huangdi (大行皇帝),

literally "the Emperor of the Great Journey."

The

Imperial Family The imperial family was made up of the emperor and the empress (皇后) as the primary consort

and Mother of the Nation (國母). In addition, the emperor would typically have several other consorts and concubines

(妃嬪), ranked by importance into a harem, in which the empress was supreme. Every dynasty had its set of rules

regarding the numerical composition of the harem. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), for example, imperial convention dictated

that at any given time there should be one Empress, one Huang Guifei, two Guifei, four fei and six pin, plus an unlimited

number of other consorts and concubines. Although the emperor had the highest status by law, by tradition and precedent the

mother of the emperor, i.e., the Empress Dowager (皇太后), usually received the greatest respect in the

palace and was the decision maker in most family affairs. At times, especially when a young emperor was on the throne, she

was the de facto ruler. The emperor's children, the princes (皇子) and princesses (公主), were often

referred to by their order of birth, e.g., Eldest Prince, Third Princess, etc. The princes were often given titles of peerage

once they reached adulthood. The emperor's brothers and uncles served in court by law, and held equal status with other court

officials (子). The emperor was always elevated above all others despite any chronological or generational superiority.

List

of Chinese Emperors and Dynasties BCQin

Dynasty - 246 Shihuang

[Zheng Wang]

- 209 Ershihuang

- 207 Sanshihuang

Han Dynasty- 206 Gaozu [Liu Bang]

- 194 Hui

- 187 Shao I

- 183 Shao II

- 179

Wen

- 156 Jing

- 140 Wu

- 86 Zhao

- 73 Xuan

- 48

Yuan

- 32 Cheng

- 6 Ai

- 1 Ping

ADUprising

(Rulers don't use personal names)- 6

Liu Ying

- 9 Wang Mang

- 23 Liu Xuan

Han Dynasty Restored- 25 Guangwu [Liu Xiu]

- 58 Ming

- 76

Zhang

- 89 He

- 106 Shang

- 107 An

- 126 Shun

- 145

Chong

- 146 Zhi

- 147 Huan

- 168 Ling

- 190 Xian

221

Three KingdomsJin Dynasty- 265 Wu [Sima Yan]

- 291 Hui

- 307 Huai

- 312

Min

- 317 Northern and

Southern Dynasties

MEDIEVAL EMPIRESui Dynasty- 580 Wen [Yang Jian]

- 605 Yang

- 617 Gong

Tang

Dynasty- 618 Gaozu [Li Yuan]

- 627 Taizong [Li Shimin]

- 650 Gaozong

- 684 Zhongzong

- 710 Ruizong

- 713 Xuanzong I

- 756

Suzong

- 763 Daizong

- 780 Dezong

- 805 Shunzong

- 806 Xianzong

- 821 Muzong

- 825

Jingzong

- 827 Wenzong

- 841 Wuzong

- 847 Xuanzong II

- 860 Yizong

- 874 Xizong

- 889

Zhaozong

- 904 Aizong

- 907 Five Dynasties

Song Dynasty- 960 Taizu [Zhao Kuangyin]

- 976 Taizong

- 998 Zhenzong

- 1023 Renzong

- 1064

Yingzong

- 1068 Shenzong

- 1086 Zhezong

- 1101 Huizong

- 1126 Qinzong

- 1127 Partition of China

MODERN EMPIREYuan

Dynasty- 1276 Kublai

- 1295 Temur

- 1308 Khaissan

- 1312 Ayurbadrabal

- 1321 Shoodbal

- 1324

Yesuntemur

- 1328 Asugbal

- 1329 Hooshal

- 1330 Tugtemur

- 1332 Renqinbar

- 1333 Togontemur

Ming

Dynasty- 1368 Hongwu [Zhu Yuanzhong]

- 1399 Jianwen

- 1403 Yongle

- 1425 Hongxi

- 1426 Xuande

- 1436

Zhengdong [later restored as Tianshun]

- 1450 Jingtai

- 1457

Tianshun [formerly Zhengdong]

- 1465 Chenghua

- 1488

Hongzhi

- 1506 Zhengde

- 1522 Jiajing

- 1567 Longqing

- 1573 Wanli

- 1620 Taichang

- 1621

Tianqi

- 1628 Zhongzhen

Qing Dynasty- 1645 Shunzhi [Aisingioro Fulin]

- 1662 Kangxi

- 1723 Yongzheng

- 1736 Qianlong

- 1796

Jiaqing

- 1821 Daoguang

- 1851 Xianfeng

- 1862 Tongzhi

- 1875 Guangxu

- 1909 Xuantong [Aisingioro Puyi]

The Qing Dynasty The Qing Dynasty was the last dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive

restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming Dynasty and followed by the Republic of China. The dynasty was founded by the Jurchen Aisin Gioro clan in contemporary Northeastern China.

The Aisin Gioro leader, Nurhachi, who was originally a vassal of the Ming emperors, began unifying the Jurchen clans in the

late sixteenth century. By 1635, Nurhachi's son Hong Taiji could claim they constituted a single and united Manchu people

and began forcing the Ming out of Liaoning in southern Manchuria.  In 1644, the Ming capital Beijing was sacked by a peasant

revolt led by Li Zicheng, a former minor Ming official who became the leader of the peasant revolt, who then proclaimed the

Shun dynasty. The last Ming ruler, the Chongzhen Emperor, committed suicide when the city fell. When Li Zicheng moved against

Ming general Wu Sangui, the latter made an alliance with the Manchus and opened the Shanhai Pass to the Manchurian army. Under

Prince Dorgon, they seized control of Beijing and overthrew Li Zicheng's short-lived Shun Dynasty. Complete pacification of

China was accomplished around 1683 under the Kangxi Emperor.  Over the course of its reign, the Qing became highly integrated

with Chinese culture. The imperial examinations continued and Han civil servants administered the empire alongside Manchu

ones. The Qing reached its height under the Qianlong Emperor in the eighteenth century, expanding beyond China's prior and

later boundaries. Imperial corruption exemplified by the minister Heshen and a series of rebellions, natural disasters, and

defeats in wars against European powers gravely weakened the Qing during the nineteenth century. "Unequal Treaties"

provided for extraterritoriality and removed large areas of treaty ports from Chinese sovereignty. The government attempts

to modernize during the Self-Strengthening Movement in the late 19th century yielded little lasting results. Losing the First

Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 was a watershed for the Qing government and the result demonstrated that reform had modernized

Japan significantly since the Meiji Restoration in 1867, especially as compared with the Self-Strengthening Movement in China.

The 1911 Wuchang Uprising of the New Army ended with the overthrow

of the Empress Dowager Longyu and the infant Puyi on February 12, 1912. Despite the declaration of the Republic of China,

the generals would continue to fight amongst themselves for the next several decades during the Warlord Era. Puyi was briefly

restored to power in Beijing by Zhang Xun in July 1917, and in Manchukuo by the Japanese between 1932 - 1945. The Imperial Chinese Titles and Styles In Chinese history there

are generally 3 levels of supreme and fully independent sovereignty or high, significantly autonomous sovereignty above the

next lower category of ranks, the aristocracy who usually recognized the overlordship of a higher sovereign or ruled

a semi-independent, tributary, or independent realm of self-recognized insufficient importance in size, power, or influence

to claim a sovereign title, such as a Duchy which in Western terms would be called a Duchy, Principality, or some

level of Chiefdom. Family members of individual sovereigns were also born to titles or granted specific titles by the sovereign,

largely according to family tree proximity, including blood relatives and in-laws and adoptees of predecessors and older generations

of the sovereign. Frequently, the parents of a new dynasty-founding sovereign would become elevated with sovereign or ruling

family ranks, even if this was already a posthumous act at the time of the dynasty-founding sovereign's accession. Titles translated in English

as "prince" and "princess" were generally immediate or recent descendants of sovereigns, with increasing

distance at birth from an ancestral sovereign in succeeding generations resulting in degradations of the particular grade

of prince or princess and finally degradation of posterity's ranks as a whole below that of prince and princess. Sovereigns

of smaller states are typically styled with lesser titles of aristocracy such as Duke of a Duchy or Marquis rather than as

hereditary sovereign Princes who do not ascend to kingship as in the European case of the Principality of Monaco, and

dynasties which gained or lost significant territory might change the titles of successive rulers from sovereign to aristocratic

titles or vice versa, either by self-designation of the ruler or through imposed entitlement from a conquering state. For

example, when Shu (state)'s kings were conquered by Qin (state), its Kaiming rulers became Marquises such as Marquis

Hui of Shu who attempted a rebellion against Qin overlords in BCE 301. Emperor of ChinaAlthough formally Tianzi, "The Son of Heaven,"

the power of the Chinese emperor varied between different emperors and different dynasties, with some emperors being absolute

rulers and others being figureheads with actual power in the hands of court factions, eunuchs, the bureaucracy or noble

families. - In the earliest,

semi-mythical age, the sovereign was titled either huang (Chinese: 皇 huáng) or di(Chinese:

帝 dì). Together, these rulers were called the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors. For the lists of the

earliest, mythological rulers, both titles are conventionally translated in English as "Sovereigns" though individual

rulers entitled either huang or di from this period are translated in English with the title "Emperor" as these

early mythological histories aim to feature the sovereigns of the evolving polity of the Chinese state, tracking those states

which can best be claimed in a roughly continuous chain of imperial primacy interspersed with several periods of disunity

such as the Spring and Autumn Period, the Warring States Period, the Three Kingdoms Period,

the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period, the republican Chinese Civil War and so on.

- The sovereigns during the Xia Dynasty and Shang

Dynasty called themselves Di (Chinese: 帝 dì); rulers of these dynasties are conventionally translated with

the title "king" and sometimes "emperor" in English even though the same term used in the mythologically

previous dynasties is conventionally translated with the title "emperor" in English.

- The sovereign during the Zhou Dynasty called themselves

Wang (Chinese: 王 or 國王; wáng), before the Qin Dynasty innovated the new term huangdi

which would become the new standard term for "emperor." The title "Wang" should not be confused with the

common surname, which, at least by middle and later Chinese historical usage, has no definite royal implications. Rulers of

these dynasties are conventionally translated with the title "king" and sometimes "emperor" in English.

- Emperor or Huangdi (皇帝, pinyin: huáng

dì) was the title of the Chinese head of state of China from the Qin Dynasty in 221 BC until the

fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. The first emperor of Qin (Qin Shi Huang) combined the two characters huang (皇

"august, magnificent") and di (帝 "God, Royal Ancestor") from the mythological

tradition and the Xia and Shang dynasties to form the new, grander title "Huangdi". Since the Han dynasty, Huangdi began

to be abbreviated to huang or di.

The title of emperor was usually transmitted from father to

son. Most often, the first-born son of theempress inherited the office, failing which the post was taken up by the first-born

son of a concubineor consort of lower rank, but this rule was not universal and disputed succession was the cause of

a number of civil wars. Unlike the case of the Japan, the emperor's regime in traditional Chinese political theory allowed

for a change in dynasty, and an emperor could be replaced by a rebel leader. This was because a successful rebel leader was

believed to enjoy the Mandate of Heaven, while the deposed or defeated emperor had lost favour with the gods, and his

mandate was over, a fact made apparent to all by his defeat. Empress - Consort - Concubine and Imperial SpousesIt was generally not accepted for a female to succeed to the throne as a sovereign regnant

in her own right, rather than playing the role of a sovereign's consort or regent for a sovereign who was still a minor in

age, so that in history of China there has only been one reigning empress, the Empress Wu, whose reign punctuated the Tang

Dynasty. However, there have been numerous cases in Chinese history where a woman was the actual power behind the imperial

throne. Hou, Empress, actually Empress Consort in English terms, was a title granted to an official primary spouse of the polygamous male Chinese Emperor, and for the mother of the

Emperor, typically elevated to this rank of Empress Dowager, bearing a senior title such as Tai Hou, Grand Empress, regardless

of which spousal ranking she bore prior to the emperor's accession. In practice, many Chinese Empress Dowagers, either as

official regent for a sovereign who was still a minor in age or from the influence of position within family social ranks,

wielded great power or is historically considered to have been the effective wielder of supreme power in China, as in the

case of Empress Dowager Cixi, Regent of China considered de facto sovereign of China for 47 years during CE 1861-1908. Imperial Madams, ranking

below Empress, aren't often distinguished in English from imperialConcubines, the next lower rank, but these were also titles

of significance within the imperial household, and Imperial Madams might be translated as Consorts with the intention

of distinguishing them from Empresses though all Empresses except the sole case of one Empress Regnant in Chinese history

are technically Empress Consorts in English terms, primacy spouses of the Emperor Regnant who is actually invested with governmental

rule. Zhou li, the Rites

of Zhou, states that Emperors are entitled to the following simultaneous spouses: - 1 Empress (皇后)

- 3 Madames or Consorts (夫人)

- 9 Imperial Concubines (嬪)

- 27 Shifus (世婦)

- 81 Imperial Wives (御妻)

Further information: Ranks of Imperial Consorts in China through

historical periods, mainly regarding ranks of imperial spouses below Empress.Hegemony - Hegemons and Ennobled FamilySovereigns styled Ba Wang, hegemon,

asserted official overlordship of several subordinate kings while refraining from claiming the title of emperor within the

imperium of the Chinese subcontinent, such as its borders were considered from era to era, as in the case of Xiang Yu who

styled himself Xīchǔ Bàwáng, Western Chu Hegemon, appointing subordinate generals from his

campaigns of conquest, including defeated ones, as Wang, kings of states within his hegemony. Royalty - Kings and Ennobled FamilyAs noted above in the section

discussing Emperors, the sovereigns during the Xia Dynasty and Shang Dynasty who called themselves Di

(Chinese: 帝 dì)and during the Zhou Dynasty who called themselves Wang (Chinese: 王 or 國王;

wáng), was the title of the Chinese head of state until the Qin Dynasty. The title "Wang" should not

be confused with the common surname, which, at least by middle and later Chinese historical usage, has no definite royal implications.

Rulers of these dynasties are conventionally translated with the title "king" and sometimes "emperor"

in English. Qin

and Han DynastyPrior to the Qin dynasty, Wang (sovereign) was the title for the ruler of whole China. Under

him were the vassals or Zhuhou ( 诸侯/諸侯 ), who held territories granted

by a succession of Zhou Dynasty kings. They had the duty to support the Zhou king during an emergency and were ranked

according to the Five Orders of Nobility. In the Spring and Autumn Period, the Zhou kings had lost most of their

powers, and the most powerful vassals became the de facto ruler of China. Finally, in the Warring States Period,

most vassals declared themselves Wang or kings, and regarded themselves as equal to the Zhou king. After

Zheng, king of the state of Qin, later known as Qin Shi Huang, defeated all the other vassals and unified China, he adopted

the new title of Huangdi (emperor). Qin Shi Huang eliminated noble titles, as he sponsoredlegalism which

believed in merit, not birth. He forced all nobles to the capital, seized their lands and turned them into administrative

districts with the officials ruling them selected on merit. After the demise of Qin Er Shi, the last Qin ruler to used

the title Huangdi (his successorZiying used the title King of Qin rather than Emperor), Xiang

Yu styled himself Hegemon King of Western Chu (Xichu Bàwáng 西楚霸王) rather than

Emperor. Xiang Yu gave King Huai of Chu II the title of Emperor of Chu (楚義帝)

or The Righteous Emperor of Southern Chu (南楚義帝) and awarded the rest of his

allies, including Liu Bang, titles and a place to administer. Xiang Yu gave Liu Bang the Principality of Han, and he

would soon replace him as the ruler of China. The founder of the Han Dynasty, Liu Bang, continued to use the title Huangdi.

In order to appease his wartime allies, he gave each of them a piece of land as their own "kingdom" (Wangguo) along

with a title of Wang. He eventually killed all of them and replaced them with members of his family. These kingdoms

remained effectively independent until the Rebellion of the Seven States. Since then, Wang became

merely the highest hereditary title, which roughly corresponded to the title of prince, and, as such, was commonly given to

relatives of the emperor. The title Gong also reverted purely to a peerage title, ranking below Wang.

Those who bore such titles were entirely under the auspices of the emperor, and had no ruling power of their own. The two

characters combined to form the rank, Wanggong, grew to become synonymous with all higher court officials. Tang Dynasty and AfterDuring the Tang Dynasty,

nobles lost most of their power to the mandarins when imperial examination replaced the nine-rank

system. Subsequent dynasties expanded the hereditary

titles further. Not all titles of peerage are hereditary, and the right to continue the heredity passage of a very high title

was seen as a very high honour; at the end of the Qing Dynasty, there were five grades of princes, amongst a myriad of

other titles. For details, see Qing Dynasty nobility. A few Chinese families enjoyed hereditary titles in the full sense, the chief among them

being the Holy Duke of Yen (the descendant ofConfucius); others, such as the lineal descendants of Wen Tianxiang,

ennobled the Duke of Xingguo, not choosing to use their hereditary title. The Imperial Clansmen consisted of those who trace

their descent direct from the founder of the Qing Dynasty, and were distinguished by the privilege of wearing a yellow

girdle; collateral relatives of the imperial house wore a red girdle. Twelve degrees of nobility (in a descending scale as

one generation succeeds another) were conferred on the descendants of every emperor; in the thirteenth generation the descendants

of emperors were merged in the general population, save that they retain the yellow girdle. The heads of eight houses, the

Iron-capped (or helmeted) princes, maintained their titles in perpetuity by rule of primogeniture in virtue of having

helped the Manchu conquest of China. All titles of nobility were officially abolished when China became a republic in

1912. They were briefly revived under Yuan Shikai's empire and after Zhang Xun's coup. The last emperor was

allowed to keep his title but was treated as a foreign monarch until the 1924 coup. Manchukuoalso had titles of nobility. The Kings and Emperors of China

|