|

Nobility of the World Volume VIII - Hungary  The front page of the Tripartitum, the

law-book summarizing the privileges of the nobility in the Kingdom of Hungary, i.e., the temporal upper stratum of the medieval

society whose special privileges were granted by law, developed gradually during the 11-14 centuries. The origin of the nobility

in the Kingdom of Hungary can be traced back to the "men distinguished by birth and dignity" (maiores natu et dignitate)

mentioned in the charters of the first kings. They descended partly from the leaders of the Magyar tribesclans and partly

from the immigrant (mainly German, Italian and French) knights who settled in the kingdom in the course of the 10-12th centuries.

By the 13th century, the royal servants (servientes regis), who mainly descended from the wealthier freemen (liberi), managed

to ensure their liberties and their privileges were confirmed in the Golden Bull issued by King Andrew II of Hungary in 1222.

Several families of the soldiers of the royal fortresses (iobagio castri) could also strengthen their liberties and they received

the status of the "true nobles of the realm" (veri nobiles regni) by the end of the 13th century, although most

of them lost their liberties and became subordinate to private castle-holders. Many leaders of the mainly Slavic, German and

Romanian colonists who immigrated to the kingdom during the 11-15th centuries also merged into the nobility. Moreover, the

kings had the authority to reward commoners with nobility and thenceforward, they enjoyed all the liberties of other nobles. From the 14th century, the idea of "one and

the same liberty" (una eademque libertas) appeared in the public law of the kingdom; the idea suggested that all the

nobles enjoyed the same privileges independently of their offices, birth or wealth. In reality, even the legislation made

a distinction partly between the members of the upper nobility (i.e., the nobles who held the highest offices in the Royal

Households and in the royal administration or, from the 15th century, who used distinctive noble titles granted by the kings)

and other nobles, and partly between nobles possessing lands and those without land possession. Moreover, public law also

recognized the existence of some groups of the "conditional nobility" (conditionarius) whose privileges were limited;

e.g., the "nobles of the Church" (nobilis ecclesiæ) were burdened with defined services to be provided to

certain prelates. In some cases, not individuals but a group of people was granted a legal status similar to that of the nobility;

e.g., the Hajdú people enjoyed the privileges of the nobility not as individuals but as a community. Similarly to other countries in Central Europe,

the proportion of the nobility in the population of the Kingdom of Hungary was significantly higher than in the western countries:

by the 18th century, about 5% of its population qualified a member of the nobility. The "cardinal liberties" of the nobility were clearly summarized

in the Tripartitum (a law book collecting the body of common laws of the Kingdom of Hungary) in 1514. According to the Tripartitum,

the nobles enjoyed personal freedom, they were submitted exclusively to the authority of the king and they were exempted of

taxation; moreover, until 1681, they were also entitled to resist any actions of the monarchs that would jeopardize their

liberties. The core privileges of the nobility were abolished or expanded to other citizens by the "April laws"

in 1848, but the members of the upper nobility could reserve their special political rights (they were hereditary members

of the Upper House of the Parliament) and the usage of names of the nobles also distinguished them from the commoners. All

the distinctive features of nobility were abolished in 1946 following the declaration of the Republic of Hungary. Prelude - before the establishment of the kingdom In the 9th century, the nomadic Magyar society

was composed mostly of freemen who were engaged in regular raids against the neighboring (mainly Slavic) peoples. Muslim geographers

mentioned that the Magyars, exercise dominion over all of the Saqlab /the Slavic people/ who are adjacent to them, and

they put upon them heavy burdens, and they are in their hands in the position of captives. -Ahmad ibn Rustah The freemen

were organized into seven (later, after the Kabars had joined their tribal federation, eight) tribes (Hungarian: törzs,

Greek: phyle), and each tribe was made of clans (Hungarian: nemzetség, Greek: genea). Although, the Magyars lived in

a stratified society, but the legal position of the freemen was still equal. Around 896, the Magyars invaded the Carpathian Basin and occupied its whole territory by

902. The occupied territory had been inhabited by mainly Slavs, Avars and Germans who became subject to the dominion of the

Magyars; on the other hand, the name of Slavic origin of certain leaders of the Magyar armies suggest that some notabilities

of the local population may have integrated themselves into the nomadic society. In the 13th century, Simon of Kéza

described in his chronicle that It came about that when the Magyars took possession of Pannonia they took prisoners of war, both Christian and non-Christian.

Some of these were put to death when they continued to offer resistance, according to the custom of nations; the more warlike

of the remainder they took with them to fight on the battlefield, and gave them a portion of the spoils; others in turn became

their property and were kept around their tents to perform various servile duties. -Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum. Following

the conquest, the Magyars made several raids to the territories of present-day Italy, Germany, France and Spain and also to

the lands of the Byzantine Empire. On one hand, the regular raids contributed to the differentiation of their society because

the leaders of the military actions were entitled to reserve a higher share of the booty for themselves, but on the other

hand, these actions could also ensure that their commoner participants kept their independent status. These military actions

also contributed to the formation of the retinues of the heads of the tribes and the clans. The regular military actions continued

westwards until the Battle of Augsburg in 955; while the raids against the Byzantine Empire finished only in 970. After (or

even before) the close of the period of the military raids, the Magyar society underwent a gradual transformation, and several

freemen was obliged to give up their nomadic lifestyle and settle down, because the Carpathian Basin did not provide vast

pastures that could have sustained a numerous nomadic population. The christianization of the Magyars commenced during the

reign of Géza, Grand Prince of the Magyars (before 972-997) who also invited western knights to settle down in his

court and granted estates to them. The formation of the Nobility - 11-12th centuries During the reign of Géza's son, King Stephen I (1000/1001-1038), who established

the Kingdom of Hungary, the Hungarian society was legally divided into two major groups. The freemen (Hungarian: szabadok, Latin: liberi) or "people of the realm" (Hungarian:

az ország népe, Latin: gens monarchiæ) still enjoyed their "golden liberties" (Hungarian: aranyszabadság,

Latin: aurea libertas); i.e., they could move within the kingdom without restrictions and they were involved into the arrangement

of public affairs. The

serfs (Hungarian: szolgák, Latin: servus) were treated as property of others. During the regin of King Stephen I., several foreign knights

immigrated to the kingdom and they received estates from the king; families of the leaders of the Magyar tribes and clans

could also reserve a part of their former possessions, provided that they accepted the king's supremacy. We inclined towards the unanimous request of the

Council that everybody should be the owner both of their properties and of the king's donations during their lifetime with

the exception those belonging to a bishopric or a county. Moreover, following their death, their sons should hold their inheritance

under similar conditions. -Section 35 of the 2nd Decree of King Stephen I.

The immigrant knights contributed to the development of the Hungarian

army, because most of them were horse-mounted men-at-arms, while during the previous centuries the Magyar troops had exclusively

been made of horse archers; only the wealthiest members of the Hungarian tribal aristocracy could follow their example, because

the maintenance of their equipment required considerable financial resources. On the other hand, light cavalry still took

a prominent part in the Hungarian military strategy and therefore other "freemen" could also reserve their independent

status provided that earned sufficient revenues from their possessions. The legal differentiation of certain groups of the "freemen" commenced during

King Stephens rule and his decrees contained different rules applicable to the "heads of counties", the "warriors"

and the "common freemen"; on the other hand, the size of the weregild payable by their murderer was still the same

according to his decrees which suggests that in theory, the "freemens" legal status was still equal. The "heads of counties" (Hungarian: ispán,

Latin: comes) lead the administration of the basic administrative units (Hungarian: vármegye, Latin: comitatus) of

the kingdom; they were appointed and dismissed by the king and thus their office was not hereditary - in contrast to the practise

the western countries had already been following by that time. The "warriors" (Hungarian: vitéz, Latin: miles) owned lands and they provided

military service to the kings or to the "counts" and King Stephen's decrees expressively urged them to join to the

ispáns' retinue. The foreign knights who were not appointed to higher offices also increased their number. The size

of the weregeld payable by them suggest that the "warriors'" financial conditions must have been close to that of

the "common freemen". The "common freemen" (Hungarian: közrendű, Latin:

vulgaris) still enjoyed their liberties (e.g., the right to free movement) and they were invited to occasional assemblies

convoked by the kings, but the number of "common freemen" who were obliged to settle down on the estates of wealthier

landowners was increasing during the period. The Notabilities, commoners and fighting serfs By the second half of the 11th century, the equal

legal status of the "freemen" had already loosened and the decrees of King Ladislaus I (1077-1095) often referred

to them as thieves or vagabonds who were to be punished with serfdom. The decisions of the Synod of Szabolcs (1092) prove

that by that time, many of the "freemen" had gone into the service of the prelates and the "counts", although

the synod also prescribed that their superiors should respect their personal freedom. Nevertheless, several "warriors"

could reserve their own possessions and independent status and they became exempted from taxation according to the decrees

of King Coloman (1095-1116). The

decrees of King Ladislaus I distinguished two groups of the freemen: The "notabilities" (Hungarian: előkelők, Latin: optimates) or "nobles"

(Hungarian: nemesek, Latin: nobilis) held the highest offices in the Royal Households and the royal administration. Their

financial conditions ensured that they could set up monasteries and grant possessions to them. The "non-nobles" (Hungarian:

nemtelenek, Latin: ignobilis) were composed of the "warriors" and the "common freemen". A new group of soldiers also appeared in the royal

documents; they were the "royal castle's serfs" (Hungarian: várjobbágyok, Latin: iobagio castri) who

did not enjoy all the liberties of the "freemen" and were personally bound to a royal castle, but they had a share

in both the royal estates attached to the castle and the tax paid by the people who were obliged to provide services to the

royal fortress. Before 1104,

King Coloman introduced a new principle when regulating the inheritance of real estates and he differentiated the lands granted

by King Stephen I on one hand, and the possessions granted by his successors on the other hand: the former were inherited

by all the male descendants of the person who received the grant, while the latter could only be inherited by the owner's

sons or (in the lack of sons) by his brothers or their sons. If a possession was granted by King Saint Stephen, it shall be inherited by all the descendants

following the order of succession. Other kings' grants shall pass from father to son, and if there is no son, the brother

shall come next; but after his death, his sons shall not be excluded from the inheritance. However, in the lack of such brothers,

the possession shall pass to the king. -Section 20 of the 1st Decree of King Coloman The Development in

the 12th century In

the course of the 12th century, the "freemen" who owned real estate and thus earned enough revenue to serve in the

kings' army strengthened their position; even their number started to increase when the kings began to grant freedom to "royal

castle's serfs" and serfs. The first example of this practise was documented by a grant made by King Géza II (1141-1162)

to a serf named Botus who had been serving in a prelate's household before, but who became absolved from his former duties

and received a smaller portion of land from the monarch. During the period, the "notabilities" who descended from

the same ancestor usually owned jointly their inherited possessions, but several examples could already be found when the

members of the family divided their inheritance among themselves. King Béla III (1172-1196) was the first monarch who alienated a whole "county"

(Modrus in Croatia) when transferred the ownership of all the royal estates in the "county" to Bartolomej who became

the ancestor of the Frankopan (Hungarian: Frangepán) family. King Andrew II (1205-1235) radically changed the internal policy his predecessors had been

following and he started to grant enormous domains to his partisans. When he expressed the substance of his "new arrangements"

(Hungarian: új berendezkedés, Latin: novæ institutiones) in one of his charters, he mentioned that Nothing can set bounds to the generosity of the

Royal Majesty; and for a monarch, the best measure of grants is immeasurableness. -King Andrew's charter (1208) From

1216, the royal charters began to mention the dignitaries of the royal administration and the Royal Households as the "barons

of the realm" (Hungarian: országbáró, Latin: baron regni) which prove that they wanted to distinguish

themselves from other nobles. They, however, could not form a hereditary aristocracy. The king's novæ institutiones endangered the liberties of the

"freemen" who owned estates in the "counties" the king had granted to his partisans, because up that time,

they had been obliged to render military services only to the kings, but the new lords of the former royal estates in the

"counties" endeavored to expand their supremacy over them. Thus, freemen serving in the kings' army commenced to

call themselves "royal servants" (Hungarian: királyi szerviensek, Latin: serviens regis) in order to express

that they were linked only to the monarch. The Golden Bull of 1222 In 1222, the "royal servants" led by former "barons of the realm" who had been dismissed by King

Andrew II enforced the king to issue the Golden Bull in order to confirm their liberties.Although, the Golden Bull still make

a distinction between the "nobles" and the "royal servants", but it also summarized the latter's liberties

in writing. According to

the Golden Bull, "royal servants" could not be arrested without a verdict and they were exempt from several taxes

payable by other freemen; moreover, the Golden Bull also declared that they were exempt from the jurisdiction of the heads

of the "counties". The privileges of the "royal servants" summarized in the royal decree established the

basis upon which the "cardinal liberties" of the nobility could be developing during the next centuries. The last

provision of the Golden Bull introduced the "right to resist" (Hungarian: ellenállási jog, Latin:

ius resistendi) based on which the prelates and the "nobles" were authorized to resist any royal measures that could

endanger their liberties confirmed by the Golden Bull. In 1231, King Andrew II issued a new charter confirming not only the

provisions of the Golden Bull, but also the liberties of the "royal castle's serfs" whose position had also been

endangered by the emerging power of the new owners of the former royal estates. The development of the lesser Nobility A deed issued, in 1232, by the "royal servants" living in Zala county indicated

a new step towards the formation of institutes of their self-government: in the deed, they passed a judgment in a case, which

proved that the "counties", that had been the basic units of the royal administration, commenced to turn into an

administrative unit governed by the developing nobility. From the 1230s, the terminology used in the royal charters when they referred to "royal servants"

began to change and finally, the Decree of 1267 issued by King Béla IV (1235-1270) identified them with the nobles.

Thenceforward, the former "royal servants" could enjoy all the privileges of the nobles and if the kings wanted

to advance commoners they rewarded them with noble status in a charter issued for this specific purpose. In the second half of the 13th century, the kings

ennobled several "royal castle's serfs" and thus they got rid of the burden to provide services to the castle holders."Royal

castle's serfs" whose estate was not charged by specific services to be provided to the castle-holders could reach the

status of nobility even without royal grant, provided that the nobles of the "county" where their estates were situated

received them into their community. The emerging power of the Barons Following the Mongol invasion of the kingdom in 1241-42, King Béla

IV endeavoured the landowners to build strongholds in their domains and therefore, he often granted lands to his partisans

with the obligation that they should build a fortress there. The wealthier members of the landed nobility endeavored to strengthen

their position and they often rebelled against the kings. They began to employ the members of the lesser nobility in their

households and thus the latter (mentioned as familiaris in the deeds) became subordinate to them. On the other hand, a familiaris

kept the ownership of his former estates and in this regard, he still reserved his liberties and fell under the jurisdiction

of the royal courts of justice. The last member of the Árpád dynasty, King Andrew III (1290-1301) tried to restore the royal

power and thus he strengthened the position of the lesser nobility against the "barons of the realm": he prescribed

the involvement of "noble judges" (Hungarian: szolgabíró, Latin: iudex nobilium) in judicial proceedings

in assize courts (Hungarian: vármegyei törvényszék, Latin: sedes iudiciaria) and he also encouraged

the nobles to take part in the law-making process by convoking assemblies for this purpose. (...) the heads of the counties shall not dare to decide the verdict

or pass a judgement without the four elected nobles." (...) once in each year, all the barons and nobles of our kingdom

shall come to the assembly in Székesfehérvár in order to discuss the state of affairs in the kingdom

and examine the barons' actions (...) -Articles 5 and 25 of the Decree of 1291 King Andrew III, however, could not hinder the strengthening

of the most powerful barons who commenced to govern their domains de facto independently of the monarch and they usurped the

royal prerogatives on their territories. Following the king's death, the largest part of the kingdom became subject to the

de facto rule of oligarchs like Máté Csák, Amade Aba and Ladislaus Kán. The Age of Chivalry - 14th century King Charles

I Robert (1308-1342), who was a matrilineal descendant of the Árpád dynasty, could strengthen his position on

the throne only following a long period of internal struggles (1301-1323) against his opponents and the most powerful oligarchs.

Based on the estates he had acquired by force from the rebellious oligarchs, the king introduced a new system in the royal

administration: when he appointed his followers to an office, he also granted them the possession of one or more royal castles

and the royal domains attached to them, but he reserved the ownership of the castle and its belongings for himself and thus

his dignitaries could only enjoy the revenues of their possessions while they held the office. King Charles I endeavoured

the implementation of the ideas of chivalry; in 1318, he established the Order of Saint George. He also set up the body of

"knights-at-the-court" (Hungarian: udvari lovag, Latin: aule regiæ miles) who acted as his personal delegates

on an ad hoc basis. King Charles I was the first king of Hungary who granted crests to his followers. In 1324, in order to

reward the nobles of Transylvania for their aid in suppressing the Saxons' rebellion, King Charles abolished the tax they

had been obliged to pay, which contributed to the unification of the nobility of the whole realm. On the other hand, during

his reign, the holders of the 20 highest offices in the public administration and the Royal Households obtained the honorific

magnificus vir that distinguished them from other nobles. In 1332, King Charles I declared in one of his charters issued to Margaret de genere Nádasd,

whose male relatives had been murdered in 1316 during the internal struggles, that she was entitled to inherit her father's

possessions. Although this privilege contradicted the customs of the kingdom that prescribed that daughters can only inherit

one-fourth of their father's estates, it set a precedent for future cases and thenceforward "putting her into a son's

place" (Hungarian: fiusítás, Latin: præfectio) became a royal prerogative and both King Charles I

and his successors exercised it occasionally in spite of the sharp opposition of the nobility. The Act of 1351 Following the

unsuccessful campaigns against the Kingdom of Naples (1347-1350) and the ravages of the Black Death (1347-1349) in the kingdom,

King Louis I (1342-1382) convoked the assembly of the "barons, notabilities and nobles" in 1351 and at their request,

he reissued the Golden Bull of 1222 with one modification. The Act also declared the principle of "one and the same liberty"

of the nobility when prescribed that (...) all the true nobles who live within the borders

of our realm, even including those who live in the duke's provinces within the borders of our realm, shall enjoy the same

liberties. -Article 11 of the Act of 1351, The modification of the Golden Bull introduced the entail system

(Hungarian: ősiség, Latin: aviticitas) when regulating the inheritance of the nobles' estates; according to the

new system, the nobles' real property could not be devised by will, but it passed by operation of law to the owner's heirs

upon his death. The Act of 1351 introduced a new tax called "ninth" (Hungarian: kilenced, Latin: nona) that was

payable by all the villeins to their lords; and the Act also prescribed, in order to prevent the wealthier land-owners from

enticing the villeins working on the smaller nobles' estate, that all the land-owners were obliged to assess the nex tax otherwise

it was payable to the king. On the other hand, King Louis I abolished the taxes the nobles living in Slavonia had been obliged

to pay thus ensuring that thenceforward they enjoyed all the liberties of the nobility of the kingdom. The Groups of "conditional Nobility" Although the Act of 1351 declared the principle

of a uniform nobility, but in reality, the legal status of some other groups of people in the kingdom was close to that of

the "real nobles of the realm", but they were burdened with defined services linked to their estates and thus their

liberties were limited. The

"nobles of the Church" (Hungarian: egyházi nemesek, prediális nemesek; Latin: nobilis ecclesiæ,

prædiales) possessed estates on some wealthier prelates' domains and served as horsemen in their lord's retinue. In

contrast to the "real nobles of the realm", they fell under the jurisdiction of the prelates, but they also set

up their own organization of self-government called "seat" (Hungarian: szék; Latin: sedes). The special legal

status of the "nobles of the Church" disappeared only in 1853. The "nobles with ten lances" (Hungarian:

tízlándzsások; Latin: nobiles sub decem lanceis constituti) lived in Szepes county (today Spiš

in Slovakia). They were exempted from the jurisdiction of the head of the county and they were organized into an autonomous

"seat".At the beginning, each of them were liable to military service, but from 1243, they had to arm only ten lance-bearers

for the kings' army. The "nobles with ten lances" could reserve their autonomy until 1804 when their "seat"

was merged into Szepes county. The "noble cnezes and voivodes"

(Hungarian: nemes kenéz, nemes vajda; Latin: nobilis kenezius, nobilis voivoda) were the leaders of the Romanians and

Ruthenians who immigrated into the kingdom and settled down there in the course of the 13-15th centuries. The kings rewarded

some voivodes and cnezes for their military service with noble status, but, initially, that status was circumscribed: they

remained obligated to pay taxes in kind for their estates, and to provide precisely-defined military services. In the 14th

century, judicial affairs in the Hátszeg (today Haţeg in Romania) district were dealt by the cnez "seats",

chaired by the Hátszeg castellan. The bishops of Várad (today Oradea in Romania) and Transylvania rewarded Romanian

voivodes who served in their military escorts with the "nobility of the Church". The bishops' semi-noble voivodes

remained in this state of dependence until the early modern period, when the Reformation did away with church estates. In

contrast, the crown's semi-noble voivodes and cnezes soon rose to the ranks of "true nobles of the realm". After

the cnezes were ennobled, their "seat" in the Hátszeg district merged with the nobiliary court of Hunyad

(today Hunedoara in Romania) county. The Rule of the Barons' leagues Following the death of King Louis I, his daughter Queen Mary I (1382-1385,

1386-1395) acceded to the throne, but the majority of the nobles opposed her rule. In 1385, the young queen had to abdicate

in favor of his distant cousin, King Charles II Ladislaus of Naples rose up in open rebellion and captured her; thus the realm

stayed without a monarch. In 1386, when the young Queen Mary I (1382-1385, 1386-1395) had been captured by rebellious nobles,

the prelates and the "barons of the realm" set up a council and they commenced to issue decrees in the name of the

"prelates, barons, notabilities and all nobles of the realm". Shortly afterwards, the members of the council entered

into a contract with Queen Mary's fiancé and elected him king; in the contract, King Sigismund (1387-1437) accepted

that his (1385-1386), but her partisans murdered the new king soon and thus she could ascend the throne again. However, the

followers of her murdered opponent's son, King, counsillors shall be the prelates, the barons, their offsprings and heirs,

of those who used to be the counsillors of the kings of Hungary The contract also recorded that the king and his counsillors would

form a league and the king could not dismiss his counsillors without the consent of the other members of the Royal Council.

In 1401, King Sigismund who had been imprisoned by the discontent members of the Royal Council, concluded a new agreement

with some members of the upper nobility who set him free. The public law of the kingdom also started to differentiate the

descendants of the "barons of the realm", even if they did not held any higher offices, from other nobles: the Act

of 1397 referred to them as the "barons' sons" (Hungarian: bárófi, Latin: filii baronum) while later

documents called them "magnates" (Hungarian: mágnás, Latin: magnates). The emerging power of the Estates - 15-16th centuries Reconstruction of the insignia of

the Order of the Dragon During his reign, King Sigismund granted several royal castles and the royal domains attached to them to the members

of the barons' leagues.The king, however, wanted to strengthen his position and for this purpose, in 1408, he founded the

Order of the Dragon. In contrast to the promises he had made, King Sigismund involved foreigners and members of the lesser

nobility in the royal administration who were mentioned as his "special counsillors" (Hungarian: különös

tanácsos, Latin: consiliarius specialis) in his documents. The king expanded the jurisdiction of the assize courts

when abolished the exemptions he or his predecessors had granted to several bodies corporate and individuals. He tried to

exempt the poorest nobles from the obligation to serve personally in his armies, but the Estates of the realm refused his

proposal, probably because exactly those who were concerned thought that this releaf could lead to the abolishment of their

personal tax-exemption. And the other nobles who do not have villains (with

the exception of those whose exemption seems reasonable because of being advanced in age, widowed or orphaned or being in

a similar state of helplessness) shall join the armies themselves alone; namely, those who have a lord and fight under his

name and at his expense, shall join together with their lord; while those without a lord, shall join together with the head

of their county at their own expense (financed from their estate or house), but also properly armed and supplied in accordance

with their capacity. -Article 3 of the Act I of 1435 The Groups within Hungarian Nobility Following the death of King Louis I (1382), the distribution of landed

property underwent a significant change in the kingdom: in parallel with a radical decrease of the size of the royal domains,

the importance of private estates increased considerably. In 1382, less than 50% of the territory of the country was owned

by nobles, but by 1437, about 65% of its territory had already been owned by them. The unequal distribution of the landed

property enabled the formation of several major groups within the nobility. The Castle of Vajdahunyad (today Castelul Huniazilor in Romania) - built in the 15th century and became the

centre of the Hunyadi domains The size of the domains

of the "magnates" (about 40 families) exceeded the 60,000 hectares (600 km2), but some of them owned landed properties

whose territory exceeded even the 300,000 hectares (3,000 km2).Their lands were cultivated by about 1,000-3,500 villeins and

they organized their domains into smaller units centered around their castles. The "magnates" employed "lesser

nobles" in their households; thus their seats turned into social and political centers in the countryside. The "wealthier nobles" (about 200-300 families)

employed 200-1,000 families of landed villeins on their estates whose size ranged from 5,000 to 60,000 hectares (from 50 to

600 km2). Most of them descended from the members of the wealthier clans of the 13th century who did not hold higher offices.

They were rich enough not to enter into the service of the magnates; therefore, they preferred to retire to their manors. The "nobles of the counties"

(about 3,000-5,000 families) owned about 20-200 villein's parcels; the size of their estates ranged from 500 to 5,000 hectares

(from 5 to 50 km2 respectively) They were employed by the "magnates" and held the highest offices in their households.

Several of them held offices in the "counties'" administration and thus became the leaders of the local "lesser

nobility". The "nobles with one parcel"

(about 12,000-16,000 families) formed the most numerous group within the nobility; the size of their estate typically did

not exceed the 3 hectares (0,3 km2) and their parcels were often cultivated by themselves without the assistance of villeins.

They were often employed as mercenaries but they also preferred the legal career; however, plenty of them worked as tailor,

blacksmith, butcher or carried out similar profession. In fact, they were peasants or craftsmen who enjoyed all the liberties

of the nobility. The majority of the "nobles with one parcel" lived in separate "noble villages", although

some of them lived together with villeins in the same settlements. According to the customary law, brothers each were entitled

to an equal share in their father's inheritance; therefore, the number of the "nobles with one parcel" were increasing

during the period because even larger estates may have been divided among their owner's descendants from generation to generation. The "nobles' in-laws" (Hungarian: agilis, nőnemes;

Latin: agilis) formed also a specific group within the nobility; they were commoners who married a noble woman or descended

from the marriage of a noble woman and a commoner. According to the customary law, the daughters of nobles inherited one-quarter

of their father's estates but their inheritance was to be delivered in cash; however, a noble's daughter was entitled to receive

her inheritance in-kind, if she married to a commoner. In this case, she and her husband became the owners of one or more

noble estates and under the customary law, her husband and their children were regarded nobles. From the 16th century, a noble

woman's commoner husband was not counted among the nobles and only their children could reach the status of nobility provided

that they inherited landed property from their mother. The Triumph of the Estates When King Albert I (1437-1439) was proclaimed king, he had to take a solemn oath that he

would exercise his prerogative powers only with the consent of the Royal Council. The Diet convoked in 1439 enacted that even

the nobles who did not have villeins be exempted from the payment of the tithe. (...) as their ancient liberties have required, nobles do not have to pay tithe whether they have villeins

or not. -Article 28 of the Act of 1439 Following King Albert's

death, a civil war broke out between the followers of his posthumous son, King Ladislaus V (1440-1457) and the partisans of

his opponent, King Vladislaus I (1440-1444). Although the infant king was crowned by the Holy Crown, but the assembly of the

Estates declared his coronation void and the Diet formulated the principle that (...) the monarchs' coronation always depends

on the will of the people of the realm, and the efficacy and the powers of the crown originate from their consent.  Between 1440 and 1458, the Diet was convoked in each year (with the exception of 1443 and

1449), and its functions changed radically: previously, the assemblies of the Estates functioned mainly as a consultative

body and the monarch passed his decrees in the Royal Council, but thenceforward, the Diet was involved in the legislative

process of law-making and the bills were to be passed by the Diet before receiving the Royal Assent. The monarch (or the regent)

sent a personal invitation to the prelates, "barons of the realm" and "magnates" when he convoked a Diet

and they attended in person at the assembly; other nobles were represented by their deputies elected at their assemblies held

in each county. Occasionally (e.g., in 1441, 1446, 1456), all the

nobles were invited to attend in person at the Diet. The constitution of the Diets ensured the predominance of the nobility,

because the "magnates" and the "counties'" deputies had an overwhelming majority over the prelates and

the towns' representatives. In 1446, the assembly of the Estates proclaimed John Hunyadi to Regent and he was to govern the

realm in cooperation with the Estates until 1453 when King Ladislaus V returned to the kingdom. John Hunyadi was the first

"magnate" who received a hereditary title from a king of Hungary  King Matthias I the Just (1458-1490) King Matthias I (1443-1490) rewarded his partisans with hereditary titles and appointed them hereditary heads of

"counties" and he also entitled them to use the red sealing wax. During his reign, all the members of the wealthier

families descending from the "barons of the realm" received the honorific magnificus which was a next step towards

their separation from other nobles. In 1487, a new expression appeared in a deed of armistice signed by King Matthias: 18

families were mentioned as "natural barons of Hungary" (Hungarian: Magyarország természetes bárói,

Latin: barones natureles in Hungaria) in contrast to the "barons of the realm" who were still the holders of the

highest offices in the public administration and the Royal Households.  King Vladislaus II the "Dobže" (1490-1516) During the reign of King Vladislaus II (1490-1516), the Diet unambiguosly expressed that certain noble families were

in a distinguished position and mentioned them as barons irrespectively of the office they held which prove that by that time,

public law had acknowledged their special legal status and their privilege to use distinctive titles. The Conflicts within the nobility and the Great Peasants' War of 1514 The period following the death of King Matthias (1490) was characterized by conflicts among

the several "parties" of the nobility, although the independence of the kingdom became more and more jeopardized

by the emerging power of the Ottoman Empire. One of the two major political groupings (the "national party") was

led by duke John Corvin (the illegitimate son of King Matthias I) and later, by count John Szapolyai and it was followed by

the majority of the "lesser nobles"; they wanted to establish a "national kingdom", i.e., they wanted

to proclaim one of the barons to king. The "court party" was composed mainly of the barons and their familiaris

and it preferred a close alliance with the Habsburgs. On the other hand, the conflict between the "upper nobility"

(the "magnates") and the "lesser nobility" also existed, because the former endeavoured to develop their

special privileges, while the latter wanted to reserve the ideology of "one and the same liberty". In 1514, the great rebellion of the peasants led

by György Dózsa broke out, and their troops occupied and burgled several manors, murdered many landowners and

raped noble women. The peasants' troops were defeated by the combined forces of the nobility led by count John Szapolyai.

The acts of revenge against the peasants were enacted by the legislation of 1514: according to the new legal provisions, thenceforward,

villeins had to work one day of each week on their lords' demesne without remuneration and their right to free movement became

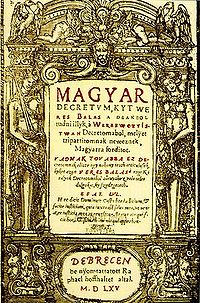

abolished. The "cardinal liberties" of the nobility - The Tripartitum  The first Hungarian translation of the Tripartitum (printed in 1565) At the Diet of 1514, István Werbőczy, who had been a member of the Royal Court,

presented his work collecting the costumary law of the realm to the Estates. Although the Diet passed a decision confirming

Werbőczy's work and his work also received the Royal Assent, but it was never promulgated, probably because it was obviously

biased towards the intresests of the "lesser nobility". Nevertheless, István Werbőczy published his work under

the title The customary law of the renowned Kingdom of Hungary: a work in three parts (Hungarian: Tekintetes Magyarország

szokásjogának hármaskönyve, Latin: Tripartitum opus iuris consuetudinarii Inclyti Regni Hungariæ)

and his book would be followed by the courts of justice in the Kingdom of Hungary during the next centuries The Tripartitum,

in contrast to the development of the public law during the 15th century, declared the principle of "one and the same

liberty" of the nobility, although it also referred to some distinctive privileges of the barons (e.g., the size of their

weregeld was higher). The

Tripartitum's Primæ Nonus (i.e., the Ninth Title of its First Part) summarized the "cardinal liberties" of

the nobility: a noble could

not be arrested without having been summonsed to appear before a court of justize and judged guilty; a noble was subordinate only

to the power of the monarch legally crowned; a noble was exempt from any taxes and obligatory services with the exemption

of military service in case of an attack on the realm; nobles were entitled to resist any act of the monarchs that could jeopardize their liberties. The Ottoman Conquest

The Battle of Mohács - August 29, 1526 On 29 August 1526, the military forces of the Kingdom of Hungary led

by King Louis II (1516-1526) suffered a catastrophic defeat from the Ottoman armies led by the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent

(1520-1566) at the Battle of Mohács. When the young king left the battlefield, he was thrown from his horse in a river

and died, weighed down by his armor. Following their victory, the Ottoman troops entered Buda and pillaged the castle and

the surroundings, but they retreated soon afterwards. The "national party" of the nobility proclaimed its leader to king, but his opponents did not

accept his rule, and shortly afterwards, they elected the Habsburg claimant to king; thus a civil war broke out among the

followers of King John I (1526-1540) and King Ferdinand I (1526-1564). When King John I died, his followers proclaimed his

infant son to king, but in 1541, the Sultan Suleiman invaded the kingdom and occupied its central parts. However, by the Sultan's

grace, the infant King John II Sigismund (1540-1570) could reserve the government in the eastern parts of the kingdom which

led to the formation of a semi-independent polity on those territories. The Kingdom of Hungary divided into three parts (in 1683) Thenceforward, the medieval Kingdom of Hungary

became divided into three parts: the western and northern

territories of the kingdom were ruled by kings from the Habsburg dynasty (Royal Hungary); the central territories of the kingdom became parts of the Ottoman Empire (Ottoman Hungary); Transylvania and other eastern territories of the kingdom turned into a semi-independent

principality under Ottoman suzerainty (Principality of Transylvania). The New Groups within the Nobility The Ottoman conquest of the central territories

of the kingdom enforced several nobles to leave their estates and they had to move to the territories that had not become

subject to the Ottoman rule. Several of them received a parcel on the domains of the "magnates", but their parcels

did not turn into noble estates and therefore, they had to pay remuneration for the use of their parcels which loosened the

principle of the personal tax-exemption of the nobility. The lack of landed property that the kings could have granted led to the practise that the monarchs commenced

to enoble communers without granting them estates; consequently, the "nobles with only letters patent" (Hungarian:

armális nemesek, armalisták; Latin: nobiles armales, armalistæ) could not serve personally in the kings'

army in the lack of proper revenues. Similarly to them, the "nobles with one parcel" neither could finance the expenses

of their personal military service. However, the permanent state of war on the borders of the Royal Hungary required the maintenance of permanent military

forces; therefore, the Estates accepted the idea that the nobles who did not owne estates cultivated by villeins (who were

obliged to pay taxes) should contribute to the expenses of the wars and in 1595, they ordered that the "nobles with only

letters patent" and the "nobles with one parcel" should pay a military contribution. Shortly afterwards, the

same nobles became subject to the tax payable for the "counties". Thenceforward, the nobles who became subject to

taxation were referred to as "nobles paying tax" (Hungarian: taksás nemesek). The Reformation in the Kingdom of Hungary Martin Luther's first adherents in the Kingdom

of Hungary appeared around 1521 among the (mainly) German-speaking citizens of the towns of Transdanubia, Upper Hungary (today

Slovakia) and (from the 1530s) Transylvania (today in Romania). Moreover, some members of German origin of the court of Mary

of Austria, the queen of King Louis II also became the follower of the church reformer's ideas. The nobility, however, endeavoured

to hinder the spreading of the ideas of the Reformation during the first half of the 16th century and the Diets of 1523, 1524

and 1525 enacted specific provisions against its followers. The Lutheran position changed when King Ferdinand I entrusted the defence of the royal fortresses

to mercenaries whose majority had become the adherent of Martin Luther and they were followed by Lutheran preachers. From

the 1530s, more and more "magnates" converted to the Lutheran ideas and the members of the lesser nobility also

followed their example. Sources Bán, Péter (editor): Magyar Történelmi Fogalomtár; Gondolat,

Budapest, 1989;

ISBN 963 282 202 1.

Benda, Kálmán (editor): Magyarország történeti

kronológiája ("The Chronology of the History of Hungary"); Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest,

1981; ISBN 963 05 2661 1.

Bóna, István: A magyarok és Európa a 9-10. században ("The

Magyars and Europe during the 9-10th centuries"); História - MTA Történettudományi Intézete,

2000, Budapest; ISBN 963 8312 67 X.

Bónis, György: Hűbériség és rendiség

a középkori magyar jogban (Vassalage and Feudality in the Medieval Hungarian Law); Osiris Kiadó, 2003,

Budapest; ISBN 963 389 426 3.

Engel, Pál - Kristó, Gyula - Kubinyi, András: Magyarország

története - 1301-1526 (The History of Hungary - 1301-1526); Osiris Kiadó, 1998, Budapest; ISBN 963 379

171 5.

Fügedi, Erik: Ispánok, bárók, kiskirályok (Counts, Barons and Petty Kings); Magvető

Könyvkiadó, 1986, Budapest; ISBN 963 14 0582 6.

Kristó, Gyula (editor): Korai Magyar Történeti

Lexikon - 9-14. század (Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History - 9-14th centuries); Akadémiai Kiadó,

1994, Budapest; ISBN 963 05 6722 9.

Kristó, Gyula: Magyarország története - 895-1301 (The History

of Hungary - 895-1301); Osiris Kiadó, 1998, Budapest; ISBN 963 379 442 0.

László, Gyula: The Magyars

- Their Life and Civilisation; Corvina, 1996; ISBN 963 13 4226 3.

Tóth, Sándor László: Levediától

a Kárpát-medencéig ("From Levedia to the Carpathian Basin"); Szegedi Középkorász

Műhely, 1998, Szeged; ISBN 963 482 175 8. References Kristó, Gyula

(1998). Magyarország története - 895-1301 (The History of Hungary - 895-1301). Budapest: Osiris Kiadó.

p. 47. ISBN 963 379 442 0.

László, Gyula (1996), The Magyars - Their Life and Civilisation, Corvina, p.

195, ISBN 963 13 4226 3

Tóth, Sándor László (1998). Levediától a Kárpát-medencéig

("From Levedia to the Carpathian Basin"). Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. pp. 78-89.

ISBN 963 482 175 8.

of Kéza, Simon (1999), The Deeds of the Hungarians, Central European University Press, p.

177, ISBN 963-9116-31-9

Bóna, István (2000). A magyarok és Európa a 9-10. században

("The Magyars and Europe during the 9-10th centuries"). Budapest: História - MTA Történettudományi

Intézete. pp. 29-65. ISBN 963 8312 67 X.

Fügedi, Erik (1986). Ispánok, bárók, kiskirályok

(Counts, Barons and Petty Kings). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó. pp. 11-27. ISBN 963 14 0582 6.

http://mek.oszk.hu/01300/01396/html/01.htm#1

Kristó, Gyula (editor) (1994). Korai Magyar Történeti Lexikon - 9-14. század (Encyclopedia of

the Early Hungarian History - 9-14th centuries). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 213-214. ISBN 963 05 6722 9.

Bán, Péter (editor) (1989). Magyar történelmi fogalomtár - I. kötet (A-K)(Dictionary

of the Terminology of the Hungarian History - Volume II /A-K/). Budapest: Gondolat. p. 43. ISBN 963 282 203 X.

. p.

102.

Bán, Péter (editor) (1989). Magyar történelmi fogalomtár - II. kötet (L-Zs)

(Dictionary of the Terminology of the Hungarian History - Volume II /L-Zs/). Budapest: Gondolat. p. 53. ISBN 963 282 204 8.

http://mek.oszk.hu/03400/03407/html/78.html

Bónis, György (2003). Hűbériség és

rendiség a középkori magyar jogban (Vassalage and Feudality in the Medieval Hungarian Law). Budapest: Osiris

Kiadó. pp. 147, 154, 157. ISBN 963 389 426 3.

http://mek.oszk.hu/03400/03407/html/73.html

http://mek.oszk.hu/03400/03407/html/81.html

Benda, Kálmán (editor) (1981). Magyarország történeti kronológiája I /A kezdetektől

1526-ig/ ("The Chronology of the History of Hungary - From the beginnings until 1526"). Budapest: Akadémiai

Kiadó. p. 260. ISBN 963 05 2661 1.

John Vitovec (1463: Zagorje county); Emeric Szapolyai (1465: Szepes county);

Nicholas Csupor de Monoszló (1467: Verőce county); John Ernuszt (1467: Turóc county); Nicholas Bánffy

de Alsólendva (1485); Peter and Matthias Geréb (1487); Fügedi, Erik, op. cit. pp. 381-382.

Article

22 of the Act of 1498.

Article 16 of the Act of 1514

Article 25 of the Act of 1514

Benda, Kálmán

(editor) (1982). Magyarország történeti kronológiája II /1526-1848/ ("The Chronology

of the History of Hungary - 1526-1848"). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 361. ISBN 963 05 2662 X.

Articles

5 and 6 of the Act of 1595

Article 54 of the Act of 1523, Article 4 of the Act of 1525

Karácsony, János

(1985). Magyarország egyháztörténete főbb vonásaiban 970-től 1900-ig (The Major

Features of the Church History of Hungary from 970 until 1900). Budapest: Könyvértékesítő Vállalat.

p. 106. ISBN 963 02 3434 3.

|