The

Holy Roman Empire (HRE; German: Heiliges Römisches Reich (HRR), Latin: Imperium

Romanum Sacrum (IRS), Italian: Sacro Romano Impero (SRI)) was a German empire that existed from 962 to 1806

in Central Europe. It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern

period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes. In its last centuries, its character

became quite close to a union of territories. The empire's territory was centered on the Kingdom of Germany, and included

neighboring territories, which at its peak included the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of Burgundy. For much of its history,

the Empire consisted of hundreds of smaller sub-units, principalities, duchies, counties, Free Imperial Cities and other domains.

In 962 Otto I was

crowned Holy Roman Emperor (German: Römisch-Deutscher Kaiser), although the Roman imperial title was first restored

to Charlemagne in 800. Otto was the first emperor of the realm who was not a member of the earlier Carolingian dynasty.

The last Holy Roman Emperor was Francis II, who abdicated and dissolved the Empire in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

In a decree following the 1512 Diet of Cologne, the name was officially changed to Holy Roman Empire of the

German Nation (German: Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation, Latin: Imperium Romanum Sacrum Nationis

Germanicæ).

The territories and dominion of the Holy Roman Empire in terms of present-day states comprised Germany

(except Southern Schleswig), Austria (except Burgenland), the Czech Republic, Switzerland and Liechtenstein, the Netherlands,

Belgium, Luxembourg and Slovenia (except Prekmurje), besides significant parts of eastern France (mainly Artois, Alsace, Franche-Comté,

French Flanders, Savoy and Lorraine), northern Italy (mainly Lombardy, Piedmont, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Trentino and South

Tyrol), and western Poland (mainly Silesia, Pomerania and Neumark).

Name

The term sacrum (i.e., "holy" in the sense of

"consecrated") in connection with the medieval Roman Empire was used from 1157, under Frederick I Barbarossa ("Holy

Empire"; the form "Holy Roman Empire" is attested from 1254 onward). The term was added to reflect Frederick's

ambition to dominate Italy and the Papacy. Before 1157, the realm was merely referred to as the Roman Empire.

In a decree following

the 1512 Diet of Cologne, the name was officially changed to Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (German:

Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation, Latin: Imperium Romanum Sacrum Nationis Germanicæ).

This form was first used in a document in 1474.

The Holy Roman Empire was named after the Roman Empire and was considered

its continuation. This is based in the medieval concept of translatio imperii. The French Enlightenment writer Voltaire

remarked sardonically: "This agglomeration which was called and which still calls itself the Holy Roman Empire was neither

holy, nor Roman, nor an empire."

History

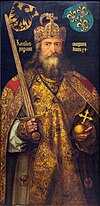

The Holy Roman Empire looked to Charlemagne,

King of the Franks, as its founder, who had been crowned Emperor of the Romans on Christmas Day in 800 by Pope Leo III. The

Western Roman Empire was thus revived (Latin: renovatio Romanorum imperii) by transferring it to the Frankish king.

This translatio imperii remained the basis for the Holy Roman Empire, at least in theory, until its demise in 1806.

The Carolingian imperial

crown was initially disputed among the Carolingian rulers of Western Francia (France) and Eastern Francia (Germany), with

first the western king (Charles the Bald) and then the eastern (Charles the Fat) attaining the prize. However, after the death

of Charles the Fat in 888, the Carolingian Empire broke asunder, never to be restored. According to Regino of Prüm, each

part of the realm elected a "kinglet" from its own "bowels." After the death of Charles the Fat, those

crowned Emperor by the Pope controlled only territories in Italy. The last such Emperor was Berengar I of Italy

who died in 924.

High Middle Ages

Around 900, East Francia saw the reemergence of autonomous stem duchies (Franconia, Bavaria,

Swabia, Saxony and Lotharingia). After the Carolingian king Louis the Child died without issue in 911, East Francia did not

turn to the Carolingian ruler of West Francia to take over the realm but elected one of the dukes, Conrad of Franconia,

as Rex Francorum Orientalum. On his deathbed, Conrad yielded the crown to his main rival, Henry of Saxony (r. 919-36),

who was elected king at the Diet of Fritzlar in 919. Henry reached a truce with the raiding Magyars and in 933 won

a first victory against them in the Battle of Riade.

Henry died in 936 but his descendants, the Liudolfing (or Ottonian)

dynasty, would continue to rule the Eastern kingdom for roughly a century. Henry's designated successor, Otto, was elected

King in Aachen in 936. He overcame a series of revolts-both from an elder brother and from several dukes. After that, the

king managed to control the appointment of dukes and often also employed bishops in administrative affairs.

The Kingdom had no

permanent capital city and the kings travelled from residence to residence (called Kaiserpfalz) to discharge affairs. However,

each king preferred certain places, in Otto's case, the city of Magdeburg. Kingship continued to be transferred by election,

but Kings often had their sons elected during their lifetime, enabling them to keep the crown for their families. This only

changed after the end of the Salian dynasty in the 12th century.

In 955, Otto won a decisive victory over the Magyars in the Battle

of Lechfeld. In 951, Otto came to the aid of Adelaide, the widowed queen of Italy, defeating her enemies. He then married

her and took control over Italy. In 962, Otto was crowned Emperor by the Pope. From then on, the affairs of the

German kingdom were intertwined with that of Italy and the Papacy. Otto's coronation as Emperor made the German kings successors

to the Empire of Charlemagne, which through translatio imperii also made them successors to Ancient Rome.

This also renewed

the conflict with the Eastern Emperor in Constantinople, especially after Otto's son Otto II (r. 967-83) adopted the designation

imperator Romanorum. Still, Otto formed marital ties with the east, when he married the Byzantine princess Theophanu.Their

son, Otto III, focused his attention on Italy and Rome and employed widespread diplomacy but died young in 1002, to

be succeeded by his cousin Henry II, who focused on Germany. When Henry II died in 1024, Conrad II, first of the Salian Dynasty,

was then elected king in 1024 only after some debate among dukes and nobles, which would eventually develop into

the collegiate of Electors.

Investiture Controversy

Kings often employed bishops in administrative

affairs and often determined who would be appointed to ecclesiastical offices. In the wake of the Cluniac Reforms, this involvement

was increasingly seen as inappropriate by the Papacy. The reform-minded Pope Gregory VII was determined to oppose such practices,

leading to the Investiture Controversy with King Henry IV (r. 1056-1106), who repudiated the Pope's interference and persuaded

his bishops to excommunicate the Pope, whom he famously addressed by his born name "Hildebrand", rather than his

divine name "Pope Gregory VII". The Pope, in turn, excommunicated the king, declared him deposed and

dissolved the oaths of loyalty made to Henry. The king found himself with almost no political support and was forced to make

the famous Walk to Canossa in 1077, by which he achieved a lifting of the excommunication at the price of humiliation. Meanwhile,

the German princes had elected another king, Rudolf of Swabia. Henry managed to defeat him but was subsequently confronted

with more uprisings, renewed excommunication and even the rebellion of his sons. It was his second son, Henry V, who managed

to reach an agreement with both the Pope and the bishops in the 1122 Concordat of Worms. The political power of

the Empire was maintained but the conflict had demonstrated the limits of any ruler's power, especially in regard to the

Church, and robbed the king of the sacral status he had previously enjoyed. Both the Pope and the German princes had surfaced

as major players in the political system of the Empire.

Hohenstaufen dynasty

When the Salian

dynasty ended with Henry V's death in 1125, the princes chose not to elect the next of kin, but rather Lothair, the moderately

powerful but already old Duke of Saxony. When he died in 1138, the princes again aimed at checking royal power; accordingly

they did not elect Lothair's favoured heir, his son-in-law Henry the Proud of the Welf family, but Conrad III of the Hohenstaufen

family, close relatives of the Salians, leading to over a century of strife between the two houses. Conrad ousted the Welfs

from their possessions, but after his death in 1152, his nephew Frederick I "Barbarossa" succeeded and made peace

with the Welfs, restoring his cousin Henry the Lion to his-albeit diminished-possessions.

The Hohenstaufen rulers increasingly

lent land to ministerialia, formerly non-free service men, which Frederick hoped would be more reliable than dukes.

Initially used mainly for war services, this new class of people would form the basis for the later knights, another basis

of imperial power. Another important constitutional move at Roncaglia was the establishment of a new peace (Landfrieden)

for all of the Empire, an attempt to (on the one hand) abolish private feuds not only between the many dukes, but on the

other hand a means to tie the Emperor's subordinates to a legal system of jurisdiction and public prosecution of criminal

acts - a predecessor of the modern concept of "rule of law". Another new concept of the time was the systematic

foundation of new cities, both by the Emperor and the local dukes. These were partly caused by the explosion in population,

but also to concentrate economic power at strategic locations, while formerly cities only existed in the shape of either

old Roman foundations or older bishoprics. Cities that were founded in the 12th century include Freiburg, possibly the economic

model for many later cities, and Munich.

Frederick was crowned Emperor in 1155 and emphasised the Empire's "Romanness",

partly in an attempt to justify the Emperor's power independently of the (now strengthened) Pope. An imperial assembly at

the fields of Roncaglia in 1158 reclaimed imperial rights in reference to Justinian's Corpus Juris Civilis. Imperial rights

had been referred to as regalia since the Investiture Controversy, but were enumerated for the first time at Roncaglia

as well. This comprehensive list included public roads, tariffs, coining, collecting punitive fees and the investiture,

the seating and unseating of office holders. These rights were now explicitly rooted in Roman Law, a far-reaching constitutional

act.

Frederick's

policies were mainly aimed at Italy, where he clashed with the increasingly wealthy and free-minded cities of the north,

especially Milan. He also embroiled himself in another conflict with the Papacy by supporting a candidate elected by a minority

against Pope Alexander III (1159-81). Frederick supported a succession of antipopes before finally making peace with Alexander

in 1177. In Germany, the Emperor had repeatedly protected Henry the Lion against complaints by rival princes or cities (especially

in the cases of Munich and Lübeck). Henry's support of Frederick's policies was only lackluster and in a critical situation

during the Italian wars, Henry refused the Emperor's plea for military support. After his return to Germany, an embittered

Frederick opened proceedings against the Duke, resulting in a public ban and the confiscation of all territories.

During the Hohenstaufen

period, German princes facilitated a successful, peaceful eastward settlement of lands previously sparsely inhabited by West

Slavs or uninhabited, by German speaking farmers, traders and craftsmen from the western part of the Empire, both Christians

and Jews. The gradual Germanization of these lands was a complex phenomenon which should not be interpreted in terms of 19th

century nationalism's bias. By the eastward settlement the Empire's influence increased to eventually include Pomerania and

Silesia - also due to intermarriage of the local, still mostly Slavic, rulers with German spouses. Also, the Teutonic Knights

were invited to Prussia by Duke Konrad of Masovia to Christianise the Prussians in 1226. The monastic state of the Teutonic

Order (German: Deutschordensstaat) and its later German successor states of Prussia however never were part of the

Holy Roman Empire.

In 1190, Barbarossa participated in the Third Crusade and died in Asia Minor. Under his son and successor,

Henry VI, the Hohenstaufen dynasty reached its apex. Henry added the Norman kingdom of Sicily to his domains, held English

king Richard the Lionheart captive and aimed to establish a hereditary monarchy, when he died in 1197. As his son, Frederick

II, though already elected king, was still a small child and living in Sicily, German princes chose to elect an adult king,

which resulted in the dual election of Barbarossa's youngest son Philip of Swabia and Henry the Lion's son Otto of Brunswick,

who competed for the crown. Otto prevailed for a while after Philip was murdered in a private squabble in 1208 until he began

to also claim Sicily. Pope Innocent III, who feared the threat posed by a union of the Empire and Sicily, now supported

Sicily's king Frederick II, who marched to Germany and defeated Otto. After his victory, Frederick did not act upon his promise

to keep the two realms separate - though he had made his son Henry king of Sicily before marching on Germany, he still reserved

real political power for himself. This continued after Frederick was crowned Emperor in 1220. Fearing Frederick's concentration

of power, the Pope finally excommunicated the Emperor. Another point was the crusade, which Frederick had promised but repeatedly

postponed. Now, though excommunicated, Frederick led the crusade in 1228, which however ended in negotiations and a temporary

restoration of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The conflict with the Pope endured who later supported the election of an anti-king

in Germany.

Despite

his imperial claims, Frederick's rule was a major turning point towards the disintegration of a central rule in the Empire.

While concentrated on establishing a modern, centralised state in Sicily, he was mostly absent from Germany and issued far-reaching

privileges to Germany's secular and ecclesiastical princes: In the 1220 Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis,

Frederick gave up a number of regalia in favour of the bishops, among them tariffs, coining, and fortification. The

1232 Statutum in favorem principum mostly extended these privileges to secular territories. Although many of these

privileges had existed earlier, they were now granted globally, and once and for all, to allow the German princes to maintain

order north of the Alps while Frederick wanted to concentrate on Italy. The 1232 document marked the first time that the

German dukes were called domini terræ, owners of their lands, a remarkable change in terminology as well.

Interregnum

After the death

of Frederick II in 1250, the German kingdom was divided between his son Conrad IV (died 1254) and the anti-king, William of

Holland (died 1256). Conrad's death was followed by the Interregnum, during which no king could achieve universal recognition

and the princes managed to consolidate their holdings and became even more independent rulers. After 1257, the crown was

contested between Richard of Cornwall, who was supported by the Guelph party, and Alfonso X of Castile, who was recognised

by the Hohenstaufen party but never set foot on German soil. After Richard's death in 1273, the Interregnum ended with unanimous

election of Rudolph I of Habsburg, a minor pro-Staufen count.

Changes in political structure

The 13th century also saw a general structural change in how land was administered, preparing

the shift of political power towards the rising bourgeoisie at the expense of aristocratic feudalism that would characterize

the Late Middle Ages.

Instead of personal duties, money increasingly became the common means to represent economic value

in agriculture. Peasants were increasingly required to pay tribute for their lands. The concept of "property"

began to replace more ancient forms of jurisdiction, although they were still very much tied together. In the territories

(not at the level of the Empire), power became increasingly bundled: Whoever owned the land had jurisdiction, from which

other powers derived. It is important to note, however, that jurisdiction at this time did not include legislation, which

virtually did not exist until well into the 15th century. Court practice heavily relied on traditional customs or rules

described as customary.

It was during this time that the territories began to transform into predecessors of modern states.

The process varied greatly among the various lands and was most advanced in those territories that were most identical to

the lands of the old Germanic tribes, e.g. Bavaria. It was slower in those scattered territories that were founded

through imperial privileges.

Late Middle Ages

The

difficulties in electing the king eventually led to the emergence of a fixed college of Prince-electors (Kurfürsten),

whose composition and procedures were set forth in the Golden Bull of 1356. This development probably best symbolises the

emerging duality between emperor and realm (Kaiser und Reich), which were no longer considered identical. This is

also revealed in the way the post-Hohenstaufen kings attempted to sustain their power. Earlier, the Empire's strength (and

finances) greatly relied on the Empire's own lands, the so-called Reichsgut, which always belonged to the king of

the day and included many Imperial Cities. After the 13th century, the relevance of the Reichsgut faded, even though

some parts of it did remain until the Empire's end in 1806. Instead, the Reichsgut was increasingly pawned to local

dukes, sometimes to raise money for the Empire, but more frequently to reward faithful duty or as an attempt to establish

control over the dukes. The direct governance of the Reichsgut no longer matched the needs of either the king or

the dukes.

Instead,

the kings, beginning with Rudolph I of Habsburg, increasingly relied on the lands of their respective dynasties to support

their power. In contrast with the Reichsgut, which was mostly scattered and difficult to administer, these territories

were relatively compact and thus easier to control. In 1282, Rudolph I thus lent Austria and Styria to his own sons.

With Henry VII, the

House of Luxembourg entered the stage. In 1312, Henry was crowned as the first Holy Roman Emperor since Frederick II. After

him all kings and emperors relied on the lands of their own family (Hausmacht): Louis IV of Wittelsbach (king 1314,

emperor 1328-47) relied on his lands in Bavaria; Charles IV of Luxembourg, the grandson of Henry VII, drew strength from

his own lands in Bohemia. Interestingly, it was thus increasingly in the king's own interest to strengthen the power of

the territories, since the king profited from such a benefit in his own lands as well.

Imperial reform

The "constitution" of the Empire was still largely unsettled at the beginning

of the 15th century. Although some procedures and institutions had been fixed, for example by the Golden Bull of 1356, the

rules of how the king, the electors, and the other dukes should cooperate in the Empire much depended on the personality

of the respective king. It therefore proved somewhat damaging that Sigismund of Luxemburg (king 1410, emperor 1433-37) and

Frederick III of Habsburg (king 1440, emperor 1452-93) neglected the old core lands of the empire and mostly resided in

their own lands. Without the presence of the king, the old institution of the Hoftag, the assembly of the realm's

leading men, deteriorated. The Imperial Diet as a legislative organ of the Empire did not exist at that time. Even

worse, dukes often went into feuds against each other that, more often than not, escalated into local wars.

Simultaneously, the

Church was in a state of crisis too, with wide-reaching effects in the Empire. The conflict between several papal claimants

(two anti-popes and the legitimate Pope) was only resolved at the Council of Constance (1414-18); after 1419, much energy

was spent on fighting the Hussites. The medieval idea of unifying all Christendom into a single political entity, of which

the Church and the Empire were the leading institutions, began to decline.

With these drastic changes, much discussion

emerged in the 15th century about the Empire itself. Rules from the past no longer adequately described the structure of

the time, and a reinforcement of earlier Landfrieden was urgently called for. During this time, the concept of "reform"

emerged, in the original sense of the Latin verb re-formare, to regain an earlier shape that had been lost.

When Frederick III

needed the dukes to finance war against Hungary in 1486 and at the same time had his son, later Maximilian I elected king,

he was presented with the dukes' united demand to participate in an Imperial Court. For the first time, the assembly of

the electors and other dukes was now called the Imperial Diet (German Reichstag) (to be joined by the Imperial Free

Cities later). While Frederick refused, his more conciliatory son finally convened the Diet at Worms in 1495, after his father's

death in 1493. Here, the king and the dukes agreed on four bills, commonly referred to as the Reichsreform (Imperial

Reform): a set of legal acts to give the disintegrating Empire back some structure. Among others, this act produced the Imperial

Circle Estates and the Reichskammergericht (Imperial Chamber Court); structures that would-to a degree-persist until

the end of the Empire in 1806.

However, it took a few more decades until the new regulation was universally accepted and

the new court actually began to function; only in 1512 would the Imperial Circles be finalised. The King also made sure that

his own court, the Reichshofrat, continued to function in parallel to the Reichskammergericht. In this year,

the Empire also received its new title, the Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation ("Holy Roman Empire

of the German Nation").

Reformation and Renaissance

In 1516, Ferdinand II of Aragon, grandfather of the future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V,

died. Due to a combination of (1) the traditions of dynastic succession in Aragon, which permitted maternal inheritance with

no precedence for female rule; (2) the insanity of Charles's mother, Joanna of Castile; and (3) the insistence by his remaining

grandfather, Maximilian I, that he take up his royal titles, Charles initiated his reign in Castile and Aragon, a union which

evolved into Spain, in conjunction with his mother. This ensured for the first time that all the realms of the Iberian peninsula

(save for Portugal) would be united by one monarch under one nascent Spanish crown, with the founding territories retaining

their separate governance codes and laws. In 1519, already reigning as Carlos I in Spain, Charles took up the imperial

title as Karl V. The balance (and imbalance) between these separate inheritances would be defining elements of

his reign, and would ensure that personal union between the Spanish and German crowns would be short-lived. The latter would

end up going to a more junior branch of the Habsburgs in the person of Charles's brother Ferdinand, while the senior branch

continued rule in Spain and in the Burgundian inheritance in the person of Charles's son, Philip II of Spain.

In addition to conflicts

between his Spanish and German inheritances, conflicts of religion would be another source of tension during the reign of

Charles V. Before Charles even began his reign in the Holy Roman Empire, in 1517, Martin Luther initiated what would later

be known as the Reformation. At this time, many local dukes saw it as a chance to oppose the hegemony of Emperor Charles V.

The empire then became fatally divided along religious lines, with the north, the east, and many of the major cities-Strasbourg,

Frankfurt and Nuremberg-becoming Protestant while the southern and western regions largely remained Catholic.

From 1515 to

1523, the Habsburg government in the Netherlands also had to contend with the Frisian peasant rebellion, led first by Pier

Gerlofs Donia and then by his nephew Wijerd Jelckama. The rebels were initially successful, but after a series of defeats,

the remaining leaders were taken and decapitated in 1523. This was a blow for the Holy Roman Empire since many major cities

were sacked and as many as 132 ships sunk (once even 28 in a single battle).

Baroque period

Charles V continued to battle the French and

the Protestant princes in Germany for much of his reign. After his son Philip married Queen Mary of England, it appeared

that France would be completely surrounded by Habsburg domains, but this hope proved unfounded when the marriage produced

no children. In 1555, Paul IV was elected pope and took the side of France, whereupon an exhausted Charles finally gave

up his hopes of a world Christian empire. He abdicated and divided his territories between Philip and Ferdinand of Austria.

The Peace of Augsburg ended the war in Germany and accepted the existence of the Protestant princes, although not Calvinism,

Anabaptism, or Zwingliism.

Germany would enjoy relative peace for the next six decades. On the eastern front, the Turks

continued to loom large as a threat, although war would mean further compromises with the Protestant princes, and so the

Emperor sought to avoid that. In the west, the Rhineland increasingly fell under French influence. After the Dutch revolt

against Spain erupted, the Empire remained neutral. A side effect was the Cologne War, which ravaged much of the upper Rhine.

After Ferdinand died

in 1564, his son Maximilian II became Emperor, and like his father, accepted the existence of Protestantism and the need

for occasional compromise with it. Maximilian was succeeded in 1576 by Rudolf II, a strange man who preferred classical

Greek philosophy to Christianity and lived an isolated existence in Bohemia. He became afraid to act when the Catholic Church

was forcibly reasserting control in Austria and Hungary and the Protestant princes became upset over this. Imperial power

sharply deteriorated by the time of Rudolf's death in 1612. When Bohemians rebelled against the Emperor, the immediate result

was the series of conflicts known as the Thirty Years' War (1618-48), which devastated the Empire. Foreign powers, including

France and Sweden, intervened in the conflict and strengthened those fighting Imperial power, but also seized considerable

territory for themselves. The long conflict so bled the Empire that it never recovered its strength.

At the Battle of

Vienna (1683), the Army of the Holy Roman Empire, led by the Polish King John III Sobieski, decisively defeated a large Turkish

army, ending the western colonial Ottoman advance and leading to the eventual dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire in Europe.

The HRE army was half Polish/Lithuanian Commonwealth forces, mostly cavalry, and half Holy Roman Empire forces (German/Austrian),

mostly infantry. The cavalry charge was the largest in the history of warfare.

The actual end of the empire came

in several steps. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which ended the Thirty Years' War, gave the territories almost complete

sovereignty. The Swiss Confederation, which had already established quasi-independence in 1499, as well as the Northern Netherlands,

left the Empire. Although its constituent states still had some restrictions-in particular, they could not form alliances

against the Emperor - the Empire from this point was a powerless entity, existing in name only. The Habsburg Emperors instead

focused on consolidating their own estates in Austria and elsewhere.

Modern period

By the rise of Louis XIV, the Habsburgs were dependent on the position

as Archdukes of Austria to counter the rise of Prussia, some of whose territories lay inside the Empire. Throughout the 18th

century, the Habsburgs were embroiled in various European conflicts, such as the War of the Spanish Succession, the War of

the Polish Succession and the War of the Austrian Succession. The German dualism between Austria and Prussia dominated the

empire's history after 1740.

From 1792 onwards, revolutionary France was at war with various parts of the Empire intermittently.

The German Mediatisation was the series of mediatisations and secularisations that occurred in 1795-1814, during the latter

part of the era of the French Revolution and then the Napoleonic Era.

Mediatisation was the process of annexing

the lands of one sovereign monarchy to another, often leaving the annexed some rights. Secularisation was the redistribution

to secular states of the secular lands held by an ecclesiastical ruler such as a bishop or an abbot.

The Empire formally

went into dormancy on 6 August 1806 when the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) abdicated,

following a military defeat by the French under Napoleon (see Treaty of Pressburg). Napoleon reorganized much of the Empire

into the Confederation of the Rhine, a French satellite. Francis' House of Habsburg-Lorraine survived the demise of the Empire,

continuing to reign as Emperors of Austria and Kings of Hungary until the Habsburg empire's final dissolution in 1918 in the

aftermath of World War I.

The Napoleonic Confederation of the Rhine was replaced by a new union, the German Confederation,

in 1815, following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. It lasted until 1866 when Prussia founded the North German Confederation,

a forerunner of the German Empire which united the German-speaking territories outside of Austria and Switzerland under

Prussian leadership in 1871. This later served as the predecessor-state of modern Germany.

Institutions

The Holy Roman Empire

was not a highly centralized state like most countries today. Instead, it was divided into dozens-eventually hundreds-of

individual entities governed by kings, dukes, counts, bishops, abbots and other rulers, collectively known as princes. There

were also some areas ruled directly by the Emperor. At no time could the Emperor simply issue decrees and govern autonomously

over the Empire. His power was severely restricted by the various local leaders.

From the High Middle Ages onwards,

the Holy Roman Empire was marked by an uneasy coexistence of the princes of the local territories who were struggling to

take power away from it. To a greater extent than in other medieval kingdoms such as France and England, the Emperors were

unable to gain much control over the lands that they formally owned. Instead, to secure their own position from the threat

of being deposed, Emperors were forced to grant more and more autonomy to local rulers, both nobles and bishops. This process

began in the 11th century with the Investiture Controversy and was more or less concluded with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia.

Several Emperors attempted to reverse this steady dissemination of their authority, but were thwarted both by the papacy and

by the princes of the Empire.

Imperial estates

The number of territories in the Empire was considerable, rising to approximately 300 at the time

of the Peace of Westphalia. Many of these Kleinstaaten ("little states") covered no more than a few square

miles, or included several non-contiguous pieces, so the Empire was often called a Flickenteppich ("patchwork

carpet").

An

entity was considered a Reichsstand (imperial estate) if, according to feudal law, it had no authority above it except

the Holy Roman Emperor himself. The imperial estates comprised:

- Territories ruled by a hereditary nobleman, such as a prince, archduke,

duke, or count.

- Territories in which

secular authority was held by a clerical dignitary, such as an archbishop, bishop, or abbot. Such a cleric was a prince of

the church. In the common case of a prince-bishop, this temporal territory (called a prince-bishopric) frequently overlapped

with his often-larger ecclesiastical diocese, giving the bishop both civil and clerical powers. Examples include the three

prince-archbishoprics: Cologne, Trier, and Mainz.

- Free

imperial cities, which were subject only to the jurisdiction of the emperor.

For a list of Reichsstände in 1792,

see List of Reichstag participants (1792).

King of the Romans

A prospective Emperor had first to be elected King of the Romans (Latin: Rex romanorum;

German: römischer König). German kings had been elected since the 9th century; at that point they were

chosen by the leaders of the five most important tribes (the Salian Franks of Lorraine, Ripuarian Franks of Franconia, Saxons,

Bavarians and Swabians). In the Holy Roman Empire, the main dukes and bishops of the kingdom elected the King of the Romans.

In 1356, Emperor Charles IV issued the Golden Bull, which limited the electors to seven: the Count Palatine of the Rhine,

the King of Bohemia, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg and the archbishops of Cologne, Mainz, and Trier. During

the Thirty Years' War, the Duke of Bavaria was given the right to vote as the eighth elector. A candidate for election would

be expected to offer concessions of land or money to the electors in order to secure their vote.

After being elected,

the King of the Romans could theoretically claim the title of "Emperor" only after being crowned by the Pope. In

many cases, this took several years while the King was held up by other tasks: frequently he first had to resolve conflicts

in rebellious northern Italy, or was in quarrel with the Pope himself. Later Emperors dispensed with the papal coronation

altogether, being content with the styling Emperor-Elect: the last Emperor to be crowned by the Pope was Charles

V in 1530.

The

Emperor had to be a man of good character over 18 years. All four of his grandparents were expected to be of noble blood.

No law required him to be a Catholic, though imperial law assumed that he was. He did not need to be a German (neither Alfonso

X of Castile nor Richard of Cornwall, who contested for the crown in the 13th century, were themselves German). By the 17th

century candidates generally possessed estates within the Empire.

Imperial Diet - Reichstag

The Imperial Diet (Reichstag, or Reichsversammlung)

was the legislative body of the Holy Roman Empire and theoretically superior to the emperor himself. It was divided into

three classes. The first class, the Council of Electors, consisted of the electors, or the princes who could vote for King

of the Romans. The second class, the Council of Princes, consisted of the other princes. The Council of Princes was divided

into two "benches," one for secular rulers and one for ecclesiastical ones. Higher-ranking princes had individual

votes, while lower-ranking princes were grouped into "colleges" by geography. Each college had one vote.

The third class was

the Council of Imperial Cities, which was divided into two colleges: Swabia and the Rhine. The Council of Imperial Cities

was not fully happy with the others; it could not vote on several matters such as the admission of new territories. The

representation of the Free Cities at the Diet had become common since the late Middle Ages. Nevertheless, their participation

was formally acknowledged only as late as in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years' War.

Imperial

courts

The Empire also had two courts: the Reichshofrat (also known in English as the Aulic Council)

at the court of the King/Emperor, and the Reichskammergericht (Imperial Chamber Court), established with the Imperial

Reform of 1495.

Imperial circles

As part of the Imperial Reform, six Imperial

Circles were established in 1500; four more were established in 1512. These were regional groupings of most (though not

all) of the various states of the Empire for the purposes of defence, imperial taxation, supervision of coining, peace-keeping

functions and public security. Each circle had its own parliament, known as a Kreistag ("Circle Diet"),

and one or more directors, who coordinated the affairs of the circle. Not all imperial territories were included within the

imperial circles, even after 1512; the Lands of the Bohemian Crown were excluded, as were Switzerland, the imperial fiefs

in northern Italy, the lands of the Imperial Knights, and certain other small territories like the Lordship of Jever.

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor (German:

Römisch-Deutscher Kaiser, or "Roman-German Emperor" Latin: Imperator Romanus

Sacer) is a term used by historians to denote a medieval ruler who had also received the title of "Emperor of the

Romans" from the Pope. After the 16th century, this elected monarch governed the Holy Roman Empire (later called

Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation), a Central European union of territories of the Medieval and Early Modern period.

Imperial

Title

The title of Emperor (Imperator) carried with it an important role as protector

of the Catholic Church. As the papacy's power grew during the Middle Ages, Popes and emperors came into conflict over church

administration. The best-known and bitterest conflict was that known as the Investiture Controversy, fought during the 11th

century between Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII.

After Charlemagne was crowned Roman Emperor by the Pope, his successors

maintained the title until the death of Berengar I of Italy in 924. No pope appointed an emperor again until the coronation

of Otto the Great in 962. Otto is considered the first Holy Roman Emperor, although Charlemagne is also accounted by some

to be the first. Under Otto and his successors, much of the former Carolingian kingdom of Eastern Francia became the Holy

Roman Empire. The various German princes elected one of their peers as King of the Germans, after which he would

be crowned as emperor by the Pope. After Charles V's coronation, all succeeding emperors were legally emperors-elect

due to the lack of papal coronation, but for all practical purposes they were simply called emperors.

The term "sacrum"

(i.e. "holy") in connection with the medieval Roman Empire was first used in 1157 under Frederick I Barbarossa.

Even though Charlemagne was the first to receive papal coronation as Emperor of the Romans, Otto I is considered the

first Holy Roman Emperor in historiography. Charles V was the last Holy Roman Emperor to be crowned by the Pope. The

final Holy Roman Emperor-elect, Francis II, abdicated in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars that saw the Empire's final

dissolution.

The

standard designation of the Holy Roman Emperor was "August Emperor of the Romans" (Romanorum Imperator Augustus).

When Charlemagne was crowned in 800, his was styled as "most serene Augustus, crowned by God, great and pacific

emperor, governing the Roman Empire," thus constituting the elements of "Holy" and "Roman" in the

imperial title. The word Holy had never been used as part of that title in official documents.

The word Roman

was a reflection of the translatio imperii (transfer of rule) principle that regarded the (Germanic) Holy

Roman Emperors as the inheritors of the title of Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, a title left unclaimed in the West after

the death of Julius Nepos in 480.

Succession

Successions to the kingship were controlled

by a variety of complicated factors. Elections meant the kingship of Germany was only partially hereditary, unlike the kingship

of France, although sovereignty frequently remained in a dynasty until there were no more male successors. Some scholars

suggest that the task of the elections was really to solve conflicts only when the dynastic rule was unclear, yet the process

meant that the prime candidate had to make concessions, by which the voters were kept on side, which were known as Wahlkapitulationen

(election capitulations).

The Electoral council was set at seven princes (three archbishops and four secular princes)

by the Golden Bull of 1356. It remained so until 1648, when the settlement of the Thirty Years' War required the addition

of a new elector to maintain the precarious balance between Protestant and Catholic factions in the Empire. Another elector

was added in 1690, and the whole college was reshuffled in 1803, a mere three years before the dissolution of the Empire.

After 1438, the Kings

remained in the house of Habsburg and Habsburg-Lorraine, with the brief exception of Charles VII, who was a Wittelsbach. Maximilian

I (Emperor 1508-1519) and his successors no longer travelled to Rome to be crowned as Emperor by the Pope. Therefore, they

could not technically claim the title Emperor of the Romans, but were mere "Emperors-elect of the Romans", as

Maximilian named himself in 1508 with papal approval. This title was in fact used (Erwählter Römischer Kaiser),

but it was somewhat forgotten that the word "erwählt" (elect) was a restriction. Of all his successors, only

Charles V, the immediate one, received a papal coronation. Before that date in 1530, he was called Emperor-elect too.

List

of Emperors

This list includes

all emperors of the Holy Roman Empire, whether or not they styled themselves Holy Roman Emperor. There are some gaps

in the tally. For example, Henry the Fowler was King of Germany but not Emperor; Emperor Henry II was numbered as his successor

as German King. The Guideschi follow the numeration for the Duchy of Spoleto.

Emperors before Otto the

Great

Traditional historiography claimed a continuity between the Carolingian Empire and the Holy Roman

Empire. This is rejected by some modern historians, who date the foundation of the Holy Roman Empire to 962. The rulers who

were crowned as Emperors in the West before 962 were as follows:

Carolingian dynasty

| Image | Name |

Life | Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Coin |

| Charles I

(Charlemagne) | 2

April 742

28 January 814 |

25 December 800 | 28 January 814 | |  |

| Louis I |

778 20 June 840 | 5 October 816 | 20 June 840 | son

of Emperor Charles I |  |

| Lothair I |

795 29 September 855 | 5 April 823 | 29 September 855 | son of Emperor Louis I |  |

| Louis II |

825 12 August 875 | 1st Easter 850

2nd 18 May 872 |

12 August 875 | son of Emperor Lothair I |  |

| Charles II |

13 June 823 6 October 877 | 29 December 875 | 6 October 877 | son

of Emperor Louis I |  |

| Charles III |

13 June 839 13 January 888 | 12 February 881 | 13 January 888 | grandson of Emperor Louis I |  |

Guideschi dynasty

| Image |

Name | Life | Coronation | Ceased

to be Emperor | Descent from

Emperor | Coin |

| | Guy |

855 12 December 894 | May 891 | 12 December 894 | great-great grandson of Emperor Charles I | |

| | Lambert |

880 15 October 898 | 30 April 892 | 15 October 898 | son of Emperor Guy | |

Carolingian dynasty

| Image |

Name | Life | Coronation | Ceased

to be Emperor | Descent from

Emperor | Coin |

| Arnulph |

850 8 December 899 | 22 February 896 | 8 December 899 | nephew of Charles III

and

great-grandson of Emperor Louis I | |

Bosonid dynasty

| Image |

Name | Life | Coronation | Ceased

to be Emperor | Descent from

Emperor | Coin |

| | Louis

III | 880 28 June 928 | 22 February 901 | 21 July 905 | grandson

of Emperor Louis II | |

Unruoching

dynasty

| Image | Name | Life | Coronation |

Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Coin |

| |

Berengar | 845 7 April 924 | December

915 | 7 April 924 |

grandson of Emperor Louis I |

|

There was no emperor in the west between 924 and 962.

Ottonian dynasty

| Image | Name | Life |

Election | Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Seal |

| 1 |

| Otto I |

23 November 912 7 May 973 | |

2 February 962 | 7 May 973 | perhaps great-great-great grandson of Emperor Louis I[citation

needed] |  |

| 2 |

| Otto II |

955 7 December 983 | 961 | 25 December 967 | 7 December 983 | son

of Emperor Otto I | |

| 3 |

| Otto III |

980 23 January 1002 | June 983 | 21 May 996 | 23 January 1002 | son

of Emperor Otto II |  |

| 4 |

| Henry II

| 6 May 973 13 July 1024 | 7 June 1002 | 14 February 1014 | 13

July 1024 | second-cousin

of Emperor Otto III

and

great-great-great grandson of Emperor Louis I |

|

Salian

dynasty

| Image |

Name | Life | Election | Coronation |

Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Seal |

| 5 |  | Conrad II

| 990 4 June 1039 | 1024 | 26

March 1027 | 4 June 1039 |

great-great-grandson of Emperor Otto I |

|

| 6 |  | Henry III |

29 October 1017 5 October 1056 | 1028 | 25 December 1046 | 5 October 1056 | son

of Emperor Conrad II |  |

| 7 |

| Henry IV |

11 November 1050 7 August 1106 | 1053 | 31

March 1084 | December

1105 | son of Emperor

Henry III |  |

| 8 |

| Henry V

| 8 November 1086 23 May 1125 | 6 January 1099 | 13 April 1111 | 23

May 1125 | son of Emperor

Henry IV |  |

Supplinburger dynasty

| Image | Name | Life | Election |

Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Seal |

| 9 |

| Lothair III

| 9 June 1075 4 December 1137 | 1125 | 4 June 1133 | 4 December 1137 | perhaps

9th generation descendant of Emperor Otto I

or

11th generation descendant of Emperor Charles II |

|

Hohenstaufen dynasty

| Image | Name | Life | Election |

Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Arms |

| 10 |

| Frederick I |

1122 10 June 1190 | 4 March 1152 | 18 June 1155 | 10

June 1190 | great-grandson

of Emperor Henry IV |  |

| 11 |

| Henry VI |

November 1165 28 September 1197 | April 1169 | 14 April 1191 | 28 September 1197 | son

of Emperor Frederick I |  |

Welf dynasty

| Image | Name | Life |

Election | Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Arms |

| 12 |

| Otto IV |

1175 or 1176 19 May 1218 | 9 June 1198 | 4 October 1209 | 1215 |

great-grandson of Emperor Lothair III |

|

Hohenstaufen dynasty

| Image | Name | Life | Election |

Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Arms |

| 13 |

| Frederick II |

26 December 1194 13 December 1250 | 1196

1215 re-election | 22 November 1220 | 13 December 1250 | son of Emperor Henry VI |  |

House of Luxembourg

| Image | Name | Life | Election |

Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Arms |

| 14 |

| Henry VII |

1275/1279 24 August 1313 | 1308 | 29 June 1312 | 24 August 1313 | 13th

generation descendant of Emperor Louis III |  |

House of Wittelsbach

| Image | Name | Life | Election |

Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Arms |

| 15 |

| Louis IV |

1 April 1282 11 October 1347 | October 1314 | 17 January 1328 | 11 October 1347 | 6th

generation descendant of Emperor Lothair III and 7th generation descendant of Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor |

|

House of Luxembourg

| Image | Name | Life | Election |

Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Arms |

| 16 |

| Charles IV |

14 May 1316 29 November 1378 | 11 July 1346/

17 June 1349 re-election |

5 April 1355 | 29 November 1378 | grandson of Emperor Henry VII |  |

| 17 |

| Sigismund |

14 February 1368 9 December 1437 | 10 September 1410/

21 July 1411 re-election |

31 May 1433 | 9 December 1437 | son of Emperor Charles IV |  |

House of Habsburg

| Image | Name | Life | Election |

Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from an Emperor | Arms |

| 18 |  | Frederick III |

21 September 1415 19 August 1493 | 1440 | 19 March 1452 | 19 August 1493 | 10th

generation descendant of Emperor Lothair III |  |

| 19 |

| Maximilian I |

22 March 1459 12 January 1519 | 16 February 1486 | |

12 January 1519 | son of Emperor Frederick III |

|

| 20 |

| Charles V |

24 February 1500 21 September 1558 | 28 June 1519 | February 1530 | 16 January 1556 | grandson

of Emperor Maximilian I |  |

| 21 |

| Ferdinand I |

10 March 1503 25 July 1564 | 1531 | | 25 July 1564 | grandson of Emperor Maximilian I |  |

| 22 |

| Maximilian II |

31 July 1527 12 October 1576 | November 1562 | |

12 October 1576 | son of Emperor Ferdinand I |

|

| 23 |

| Rudolph II

| 18 July 1552 20 January 1612 | 1575 | 30 June 1575 | 20 January 1612 | son

of Emperor Maximilian II |  |

| 24 |

| Matthias |

24 February 1557 20 March 1619 | 1612 | 23

January 1612 | 20 March

1619 | son of Emperor

Maximilian II |  |

| 25 |

| Ferdinand II |

9 July 1578 15 February 1637 | 1618 | 10 March 1619 | 15 February 1637 | grandson

of Emperor Ferdinand I |  |

| 26 |

| Ferdinand III |

13 July 1608 2 April 1657 | 1636 | 18

November 1637 | 2 April

1657 | son of Emperor

Ferdinand II |  |

| 27 |

| Leopold I |

9 June 1640 5 May 1705 | July 1658 | 6 March 1657 | 5

May 1705 | son of Emperor

Ferdinand III |  |

| 28 |

| Joseph I |

26 July 1678 17 April 1711 | 6 January 1690 | 1 May 1705 | 17

April 1711 | son of Emperor

Leopold I |  |

| 29 |

| Charles VI |

1 October 1685 20 October 1740 | 12 October 1711 | 22 December 1711 | 20 October 1740 | son

of Emperor Leopold I |  |

House of Wittelsbach

| Image | Name | Life | Election |

Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from Emperor | Arms |

| 30 |

| Charles VII

| 6 August 1697 20 January 1745 | 24 January 1742 | 12 February 1742 | 20 January 1745 | great-great

grandson of Emperor Ferdinand II and 12th generation descendant of Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor |

|

House of Habsburg-Lorraine

| Image | Name | Life | Election |

Coronation | Ceased to be Emperor | Descent from an Emperor | Arms |

| 31 |  | Francis I |

8 December 1708 18 August 1765 | 13 September 1745 | |

18 August 1765 | great grandson of Emperor Ferdinand III |

|

| 32 |

| Joseph II |

13 March 1741 20 February 1790 | after 18 August 1765 | 19 August 1765 | 20 February 1790 | son of Emperor Francis I |

|

| 33 |

| Leopold

II | 1747 to 1792 | | 30 September

1790 | 1 March

1792 | son of Emperor Francis I |  |

| 34 |  |

Francis II | 12 February 1768 2 March 1835 | after 1 March 1792 | 4 March 1792 | 6

August 1806 | son of

Emperor Leopold II |  |

Coronation

The Emperor was crowned in a special ceremony, traditionally performed by the Pope in Rome, using the Imperial Regalia. Without

that coronation, no king, despite exercising all powers, could call himself Emperor. In 1508, Pope Julius II allowed Maximilian

I to use the title of Emperor without coronation in Rome, though the title was qualified as Electus Romanorum Imperator

("elected Emperor of the Romans"). Maximilian's successors adopted the same titulature, usually when they became

the sole ruler of the Holy Roman Empire[citation needed]. Maximilian's first successor Charles V was

the last to be crowned Emperor.

| Emperor | Coronation date | Officiant |

Location |

| Charles I | 25

December 800 | Pope Leo III |

Rome |

| Louis I | Jul/Aug

816 | Pope Stephen V |

Reims |

| Lothair I | 5

April 823 | Pope Paschal I |

Rome |

| Louis II | April

850 | Pope Leo IV |

Rome |

| Charles II | 29

December 875 | Pope John

VIII | Rome |

| Charles III | 12 February 881 | |

| Guy III of Spoleto | May 891 | Pope Stephen V | |

| Lambert II of Spoleto | 30 April 892 | Pope Formosus | Ravenna |

| Arnulf of Carinthia | 22 February 896 | Rome |

| Louis

III | 15 or 22 February 901 |

Pope Benedict IV | Rome |

| Berengar |

December 915 | Pope John X | Rome |

| Otto I | 2 February, 962 | Pope

John XII | |

| Otto II | 25 December, 967 | Pope

John XIII | |

| Otto III | 21 May, 996 | Pope

Gregory V | |

| Henry II | 14 February 1014 | Pope

Benedict VIII | |

| Conrad II | 26 March 1027 | Pope

John XIX | |

| Henry III | 25 December 1046 | Pope

Clement II | |

| Henry IV | 31 March 1084 | Antipope

Clement III | |

| Henry V | 13 April 1111 | Pope

Paschal II | |

| Henry V | 23 March 1117 | Antipope

Gregory VIII | |

| Lothair III | 4 June 1133 | Pope

Innocent II | Basilica of St. John Lateran |

| Frederick I | 18 June 1155 | Pope

Adrian IV | |

| Henry VI | 14 April 1191 | Pope

Celestine III | |

| Otto IV | 4 October 1209 | Pope

Innocent III | |

| Frederick II | 22 November 1220 | Pope Honorius III | |

| Henry VII | 29 June 1312 | Cardinals |

|

| Louis IV | 17

January 1328 | Sciarra Colonna |

|

| Charles IV | 5

April 1355 | Cardinal |

|

| Sigismund | 31

May 1433 | Pope Eugenius IV |

|

| Frederick III | 19

March 1452 | Pope Nicholas V |

|

| Charles V | February

1530 | Pope Clement VII |

Bologna, Italy |