Nobility of the World

Volume VIII - Germany

The German nobility (German: Adel) was

the elite hereditary ruling class or aristocratic class in the Holy Roman Empire and what is now Germany. In Germany, nobility

and titles pertaining to it were bestowed on a person by higher sovereigns and then passed down through legitimate children

of a nobleman. Alternatively, unlike men, women could legally become members of nobility by marrying a noble, although they

could not pass it on. Nobility and titles (except for most reigning titles) were always inherited equally by all legitimate

descendants of a nobleman.

The

German nobility as a legally defined class was abolished on August 11, 1919 with the Weimar Constitution, under which all

Germans were made equal before the law, and the legal rights and privileges due to nobility ceased to exist. The German nobility

continues to play an important role in the various European nations that have not abolished the nobility. Most of the European

royal families are descendants of the German nobility. Most famously, close family relations exist between England's House

of Windsor and the Prussian Hohenzollern family, of which the last German emperor Wilhelm II. was a member.

Most, but not all, surnames of the German nobility

were preceded by or at least contained the preposition von, meaning of, and sometimes by zu, which is usually translated as

of when used alone or as in, at, or to. The two were occasionally combined into von und zu, meaning of and at approximately.

In general, the "von" form indicates the place the family originated, while the "zu" form indicates that

they are currently in possession of a certain place, therefore ''von und zu" indicates a family still in possession of

their original feudal holding or residence. Other forms also exist as combinations with the definitive article: e.g. "von

der" or von dem → "vom" ("of the"), zu der → "zur" or zu dem → "zum"

("of the", "in the", "at the"). An example is Count Kasimir von der Recke.

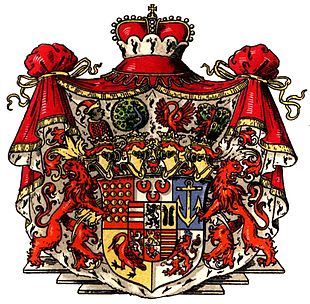

Heraldic arms of the Holy Roman Empire

Siebmachers

Wappenbuch

Although nobility as a class of privileged

status has been abolished in Germany, nobles were allowed to keep their titles, a provision which is still in place today.

Unlike before the Weimar Constitution, however, they have become part of a person's legal surname. Accordingly, the aforementioned

Count Kasimir von der Recke would today legally be called Kasimir Count von der Recke.

Like nobles elsewhere, German nobles were acutely

aware of and proud of their superior social position, and often had disdain for commoners. As shown in Theodor Fontane's novel

Effi Briest, they referred to one another as Geborene, or "those who have been born", while commoners were called

Geworfene, corresponding roughly to "whelped", "calved", or "foaled" in English, and properly

referring only to non-human birth.

Many different states within Imperial Germany had sometimes very strict laws concerning conduct, lineage, and marriage

of nobles. Failure to obey these provisions often resulted in Adelsverlust, or loss of the status of nobility. Until about

the early 19th century, for example, it was commonly forbidden for nobles to marry people "of low birth", i.e. commoners.

Some states exercised the punishment of Adelsverlust also on nobles sentenced to prison or convicted of serious felonies,

on persons engaging in "lowly labor", or for otherwise grave and unbecoming misconduct. This punisment only affected

individuals, not a noble family in its entirety.

Although nobility in its legal significance was abolished in 1919, various different German organizations

perpetuate the noble heritage to this day, and for example decide on matters of lineage as well as chronicling the history

of noble families. German noble families were almost always armigerous, entitled to bear a coat of arms.

The Divisions of German Nobility

Uradel (ancient nobility): Nobility that dates back

to at least the 1500s, and originates from leadership positions during the Migration Period. This contrasts with:

Briefadel

(patent nobility): Nobility by letters patent. The first known such document is from September 30, 1360 for Wyker Frosch in

Mainz.

Hochadel (high nobility): Nobility that was sovereign or had a high

degree of sovereignty. This contrasts with:

Niederer Adel (lower nobility): Nobility that had a lower degree of

sovereignty.

The Titles and

Ranks of German Nobility

These

titles were at one time used by various rulers. The titles Archduke, Duke, Prince, Margrave (and all other -graves), Count,

Count Palatine and Lord were also used by non-sovereign members of some of these families or by noble non-reigning families.

Title (English) Title (German) Territory

(English) Territory (German)

Emperor/Empress Kaiser(in) Empire Kaiserreich, Kaisertum

King/Queen König(in) Kingdom Königreich

Elector/Electress Kurfürst(in) Electorate Kurfürstentum

Archduke/Archduchess Erzherzog(in) Archduchy Erzherzogtum

Grand Duke/Grand

Duchess Großherzog(in) Grand Duchy Großherzogtum

Duke/Duchess Herzog(in) Duchy Herzogtum

Count(ess)

Palatine Pfalzgraf/Pfalzgräfin County Palatine Pfalzgrafschaft

Margrave/Margravine Markgraf/Markgräfin Margraviate,

March Markgrafschaft

Landgrave/Landgravine Landgraf/Landgräfin Landgraviate Landgrafschaft

Burgrave/Burgravine Burggraf/Burggräfin Burgraviate Burggrafschaft

Prince(ss) Fürst(in) Principality Fürstentum

Count(ess)

of the Empire Reichsgraf*/Reichsgräfin County Grafschaft

Altgrave/Altgravine Altgraf/Altgräfin Altgraviate Altgrafschaft

Baron(ess) Freiherr/Freifrau/Freiin* (Allodial)

Barony Freiherrschaft

Lord Herr Lordship Herrschaft

Knight Reichsritter*

The Non-Reigning Titles of Germany

Titles for junior members of Sovereign Families and for Non-Sovereign Families

Title (English) Title (German)

Crown Prince(ss) Kronprinz(essin)

Archduke/Archduchess Erzherzog(in)

Prince(ss) Prinz(essin)

Duke/Duchess Herzog(in)

Prince(ss) Fürst(in)

Margrave/Margravine Markgraf/Markgräfin

Landgrave/Landgravine Landgraf/Landgräfin

Count(ess)

Palatine Pfalzgraf/Pfalzgräfin

Burgrave/Burgravine Burggraf/Burggräfin

Altgrave/Altgravine Altgraf/Altgräfin

Count(ess)

of the Empire Reichsgraf/Reichsgräfin

Baron(ess) of the Empire Reichsfreiherr/Reichsfreifrau/Reichsfreiin

Count(ess) Graf/Gräfin

Baron(ess) Freiherr/Freifrau/Freiin

Lord / Noble

Lord Herr /Edler Herr

Knight (grouped with untitled nobles) Ritter

Noble (Von Halffter) Edler/Edle

Young Lord

(grouped with untitled nobles) Junker

The heirs

to some nobles or sovereigns had special titles of their own prefixed by Erb-, meaning Hereditary. For instance, the heir

to a Grand Duke is titled Erbgroßherzog, meaning Hereditary Grand Duke. A sovereign duke's heir might be titled ErbherzogErbprinz (Hereditary Duke, Hereditary Prince) and a prince's

heir might be titled Erbprinz or Erbgraf (Hereditary Prince, Hereditary Count), also Erbherr. The prefix distinguished the

heir from similarly-titled junior siblings.

Graf is a historical German noble title equal in rank to a count (derived from the Latin Comes, with a

history of its own) or a British earl (an Anglo-Saxon title akin to the Viking title Jarl). A derivation ultimately from the

Greek verb graphein 'to write' may be fanciful: Paul the Deacon wrote in Latin ca 790: "the count of the Bavarians that

they call gravio who governed Bauzanum and other strongholds..." (Historia gentis Langobardorum, V.xxxvi); this may be

read to make the term a Germanic one, but by then using Latin terms was quite common. Since August 1919, in Germany, Graf

and all other titles are considered as a part of the name. The

comital title Graf has of course also been used by German-speakers (as official or vernacular language), also in Austria and

other Habsburg crown lands (mainly Slavic and Hungary), in Liechtenstein and much of Switzerland.

A Graf (Count) ruled over a territory known as

a Grafschaft, literally 'countship' (also rendered as 'county'). The comital titles awarded in the Holy Roman Empire often related to the jurisdiction or domain of responsibility

and represented special concessions of authority or rank. Only the more important titles remained in use until modern times.

Many Counts were titled Graf without any additional qualification. For a list of the titles

of the rank of Count etymologically related to Graf (and for other equivalents) see article Count.

The List of Nobiliary Titles containing the Term Graf

German English Comment/ etymology

Markgraf Margrave (only continental) and

(younger)

Marquess or Marquis Mark: march (border province) + Graf

Landgraf Landgrave Land (country) + Graf

Reichsgraf Count of the Empire Reich i.e., (the Holy Roman) Empire + Graf

Gefürsteter Graf Princely Count German verb

for "to make into a Reichsfürst" + Graf

Pfalzgraf Count Palatine

or Palsgrave (the latter is archaic in English) Pfalz (palatial estate, Palatinate) + Graf

Rheingraf Rhinegrave Rhein (river Rhine) + Graf

Burggraf Burgrave Burg (castle, burgh) + Graf

Altgraf Altgrave Alt (old) + Graf (very rare)

Freigraf Free Count Frei = free (allodial?) + Graf;

both a feudal title of comital rank and a more technical office

Wildgraf Wildgrave Wild (game or wilderness) + Graf

Raugraf Raugrave Rau (raw, uninhabited, wilderness) + Graf

Vizegraf Viscount Vize = vice- (substitute) + Graf

The Title of Reichsgraf, Gefürsteter Graf

A Reichsgraf was a nobleman whose title of count

was conferred or confirmed by the Holy Roman Emperor, and literally meant "count of the (Holy Roman) Empire". Since

the feudal era any count whose territory lay within the Empire, was under the immediate jurisdiction of the Emperor, and exercised

a shared vote in the Reichstag came to be considered a member of the "upper nobility" (Hochadel) in Germany, along

with princes (Fürsten), dukes (Herzöge), electors, and the emperor himself. A count who was not a Reichsgraf was

apt to possess only a "mediate" fief (Afterlehen) - he was subject to an immediate prince of the empire, such as

a duke or elector.

However,

the Holy Roman Emperors also occasionally granted the title of Reichsgraf to subjects and foreigners who did not possess and

were not granted immediate territories -- or, sometimes, any territory at all. Such titles were purely honorific. In English,

Reichsgraf is usually translated simply as count and is combined with a territorial suffix (e.g. Count of Holland, Count Reuss,

or a surname Count Fugger, Count von Browne. But even after the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the Reichsgrafen

retained precedence above other counts in Germany. Those who had been quasi-sovereign until German mediatisation retained,

until 1918, status and privileges pertaining to members of reigning dynasties. A gefürsteter Graf (in English, princely

count) is a Reichsgraf who has been made Reichsgraf by an act of the king, as opposed to one whose ancestors have held this

privilege since the High Middle Ages.

The Notable Reichsgrafen included:

Castell

Fugger

Henneberg

Leiningen

Nassau-Weilburg

Pappenheim

Tyrol

Stolberg

A complete list of Reichsgrafen as of 1792 can be found in the List of Reichstag participants (1792).

The Title of Landgrave

A Landgraf or Landgrave was a nobleman of comital

rank in feudal Germany whose jurisdiction stretched over a sometimes quite considerable territory. The title survived from

the times of the Holy Roman Empire. The status of a landgrave was often associated with sovereign rights and decision-making

greater than those of a simple Graf (Count), but carried no legal prerogatives.

Landgraf occasionally continued in use as the subsidiary title of such nobility as the Grand

Duke of Saxe-Weimar, who functioned as the Landgrave of Thuringia in the first decade of the 20th century; but the title fell

into disuse after World War I. The jurisdiction of a landgrave was a Landgrafschaft landgraviate and the wife of a landgrave

was a Landgräfin or landgravine. Examples: Landgrave of Thuringia, Landgrave of Hesse (later split in Hesse-Kassel and

Hesse-Darmstadt), Landgrave of Leuchtenberg.

The Title of Gefürsteter Landgraf

A combination of Landgraf and Gefürsteter Graf (both above). Example: Leuchtenberg,

later a duchy.

The Title

of Burgrave / Viscount

A

Burggraf, or Burgrave, was a 12th and 13th century military and civil judicial governor of a castle (compare Castellan, Custos,

Keeper) of the town it dominated and of its immediate surrounding countryside. His jurisdiction was a Burggrafschaft, burgraviate.

Later the title became ennobled and hereditary

with its own domain. Example: Burgrave of Nuremberg. It occupies the same relative rank as titles rendered in purist German

by Vizegraf, in Dutch as Burggraaf or in English as Viscou (Latin: Vicecomes), in origin also a deputy of a Count, as the

burgrave dwelt usually in a castle or fortified town. Soon many became hereditary and almost-a-Count, ranking just below the

'full' Counts, but above a Freiherr (Baron). It was also often used as a courtesy title by the heir to a Graf.

The Titles of Rhinegrave, Wildgrave, Raugrave,

Altgrave

Unlike the other

comital titles, the titles of Rhinegrave, Wildgrave (Waldgrave), Raugrave, and Altgrave are not generic titles. Instead, each

is linked to one specific countship. By rank, these unusually named counts are equivalent to other counts.

"Rhinegrave" (German Rheingraf) was the

title of the count of the Rheingau, a county located between Wiesbaden and Lorch on the right bank of the Rhine. Their castle

was known as the Rheingrafenstein. After the Rhinegraves inherited the Wildgraviate (see below) and parts of the Countship

of Salm, they called themselves Wild- and Rhinegraves of Salm.

When the Nahegau (a countship named after the river Nahe) split into two parts in 1113,

the counts of the two parts called themselves Wildgraves and Raugraves, respectively. They were named after the geographic

properties of their territories: Wildgrave (Wildgraf), in Latin comes sylvanus, after Wald ("forest"), Raugrave

(Raugraf), in Latin comes hirsutus, after the rough (i.e., mountainous) terrain.

The first Raugrave was Count Emich I (died 1172). The dynasty died out in the 18th century. The title was taken over

after Elector Palatine Karl Ludwig I purchased the estates, and after 1667 was owned by the children from the Elector's bigamous

(morganatic) second marriage to Karl's wife, Marie Louise von Degenfeld.

Altgrave (German Altgraf, "old count")

was a title used by the counts of Lower Salm to distinguish themselves from the Wild- and Rhinegraves of Upper Salm, since

Lower Salm was the senior branch of the family.

Furthermore, the term -graf occurs in various office titles which

did not attain nobiliary status, but were either held as a sinecure by nobleman or courtiers, or by those who remained functional

officials, such as the Deichgraf (in a polder management organism).

The German Junker

Nobility

A Junker (English

pronunciation: /ˈjʊŋkər/ YOONG-kər, German: [ˈjʊŋkɐ]) was a member of the landed

nobility of Prussia and eastern Germany. These families were mostly part of the German Uradel (very old feudal nobility) and

carried on the colonization and Christianization of the northeastern European territories during the medieval Ostsiedlung.

Today "Junker" is often used as an honorific for untitled German nobility. The abbreviation of Junker is Jkr. and

is most often placed before the given name and academic titles, for example: Jkr. Heinrich von Hohenberg. The female equivalent

Junkfrau (Jkfr.) is used only sporadically. In the past the honorific Jkr. was also used for Barons and Counts.

The Origins of The Junker Nobility

"Junker" in German means "young

lord", and is understood as country squire. It is probably derived from the German words Junger Herr, or Young Lord.

As part of the nobility, many Junker families have particles such as "von" or "zu" before their family

names. In the Middle Ages, a Junker was simply a lesser noble, often poor and politically insignificant. Martin Luther was

given the pseudonym "Junker Jörg" while he lived in Wartburg Castle in 1521. A good number of poor Junkers

took up careers as soldiers and mercenaries. Over the centuries, they rose from disreputable captains of mercenary cutthroats

to influential commanders and landowners in the 19th century, especially in the Kingdom of Prussia.

The Modern influences

Being the bulwark of Hohenzollern Prussia, the

Junkers controlled the Prussian Army, leading in political influence and social status, and owning immense estates, especially

in the north-eastern half of Germany (Brandenburg, Mecklenburg, Pomerania, East Prussia, Saxony, Silesia). Their political

influence extended from the German Empire of 1871-1918 through the Weimar Republic of 1919-1933. It was said that "if

Prussia ruled Germany, the Junkers ruled Prussia, and through it the Empire itself."

They dominated all the higher civil offices and officer corps. Supporting

monarchism and military traditions, they were often reactionary and protectionist; they were often anti-liberal, siding with

the conservative monarchist forces during the Revolution of 1848. Their political interests were served by the German Conservative

Party in the Reichstag and the extraparliamentary Agrarian League. This political class held tremendous power over the industrial

classes and the government. When Chancellor Caprivi reduced the protective duties on imports of grain, these landed magnates

demanded and obtained his dismissal; and in 1902, they brought about a restoration of such duties on foodstuffs as would keep

the prices of their own products at a high level.

The German statesman Otto von Bismarck was a noted Junker, as were President Paul von Hindenburg and Field

Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt. The Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, staged by Adolf Hitler and General Erich Ludendorff was foiled by

commander Otto von Lossow of the local Reichswehr, and the Bavarian Prime Minister Gustav von Kahr. Kahr was later murdered

in the Night of the Long Knives (the Blood Purge) of June 30, 1934. This series of events, as well as a few others, led Hitler

to dislike Junkers in general. However, Hitler mostly ignored the Junkers as a whole during his time in power, taking no action

against them and no action in their favour.

As World War II turned against Nazi Germany and Nazi atrocities were revealed, several Junkers in influential

positions participated in Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg's assassination attempt of 20 July 1944. Fifty-eight were executed

when the plot failed. During the war and subsequent expulsion of Germans from eastern Europe, the majority of the Junkers

were also killed. Only about 15% made it to the Western zone of occupation.

Bodenreform

As landed aristocrats, the Junkers owned most of the arable land in the Prussian and eastern German states.

This was in contrast to the Catholic southern States such as Bavaria, Württemberg or Baden, where land was owned by small

farms, or the mixed agriculture of the western states like Hesse or Westphalia. This gave the Junkers a virtual monopoly on

all agriculture in the German states east of the Elbe river.

After World War II, during the Bodenreform (land reform) in the German Democratic Republic

(GDR), all private property exceeding a certain area was nationalised and redistributed to Landwirtschaftliche Produktionsgenossenschaften

(agricultural cooperatives). As most of these large estates belonged to Junkers, the government promoted their plans with

the slogan "Junkerland in Bauernhand!" ("Junker land into farmers hand").

After German reunification, some Junkers tried to regain their former

estates through civil lawsuits. However, the German courts have upheld the land reforms and rebuffed all claims for compensation.

The last decisive case being the unsuccessful lawsuit of Ernst August, Prince of Hanover, in September 2006, where the federal

courts decided that the prince had no right to compensation. Other families, however, have quietly purchased or leased back

their ancestral homes from the current owners (often the German federal government in its role as trustee).

The Nobility of The Holy Roman

Empire

The Holy Roman

Empire of the German Nation, formally became dormant by a decision of the last Emperor, Francis II, on 6 August 1806, had

already long ceased to be a major political power even though the prestige of the Imperial title conferred immense status

and influence. Indeed, its description as neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire was peculiarly apposite. The Holy Roman,

or German Empire as it should better be described, could justly claim to be the successor of the Western Roman Empire despite

its later foundation. Although the Eastern Empire of Byzantium, which expired in 1453, had enjoyed an unbroken succession

from the time of Constantine the Great, its claim to jurisdiction beyond the boundaries of the western Balkans was never acknowledged.

The Empire of the Germans was founded by Charles

the Great (Charlemagne), whose coronation on Christmas Day 800 gave Papal approval to the unification of France, most of modern

Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, and northern Italy under his rule. Although his male line descendants had

died out within little more than a century, Charlemagne is the ancestor of every existing Christian European ruling or former

ruling dynasty. The only modern survivors of the Empire are the ecclesiastical Princes - the German Archbishops and Bishops

- and the Sovereign Princes of Liechtenstein. With the death of Charlemagne no ruler until Napoleon ever held sway over his

lands and the Imperial title became the legacy of the Germans.

The Emperor, although himself usually an hereditary ruler of one or more states within the

Empire, was elected to office. Nonetheless, several dynasties managed to perpetuate their grip upon the Imperial title. The

surest means of establishing dynastic rule was for the Emperor to insure that his immediate heir was the inevitable choice

of the "Electors" by having him nominated King of the Romans in his own lifetime. Those Princes who, by the early

thirteenth century, had established their claim to the title of Electors of the Empire were the Prince Archbishops of Köln

(Archchancellor of Italy), Trier (Archchancellor of Gaul) and Mainz (Archchancellor of Germany), the King of Bohemia (Imperial

Cup Bearer) the Duke of Saxony (Imperial Marshal), the Count Palatine of the Rhine (Imperial Seneschal), and the MarkGraf

(Margrave in English) of Brandenburg. Their number was formerly codified in an Imperial Bull of 1356 issued by the Emperor

Karl IV (of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia). That this Bull was issued without reference to Papal authority indicates the decline

of Papal power since the Avignon schism. Henry IV's humiliation at Canossa would never be repeated.

The Reformation was the

greatest blow to Imperial power, resulting in increasing Hohenzollern power with the acquisition of the Duchy of Prussia and

the conversion of Church lands into hereditary fiefs. The religious wars of the sixteenth century and the Thirty Years war

in the early seventeenth led to a further diminution of Imperial power, even though the Habsburgs' rule in Bohemia was consolidated.

The number of Electors was increased to eight with the elevation of the Wittelsbach Duchy of Bavaria to the status of Electorate

(giving that family two Electors, the other being the Elector Palatine) in 1648, following the changes wrought by the Thirty

Years war. In 1692 a fourth was added in the person of the Duke of Brunswick-Luneburg-Hannover, who became Elector of Hannover

(united with the British crown in 1714). Shortly before the collapse of the Empire, the Emperor Napoleon imposed his own reorganization

of the German states and four more princes were added to the ranks of the Electors (three lay Electors, Hesse-Cassel, Baden

and Wurtemberg, and one ecclesiastical, the Archbishop of Salzburg - an Austrian Archduke) while the Archbishops of Mainz,

Trier and Köln lost their sovereignty and electoral rank.

From 1438 until 1740 the Imperial Crown was held continually by the Habsburgs, who initially

did not hold an Electoral seat. The German Electors, however, chose the first Habsburg Emperors because most of their hereditary

territories were outside the formal boundaries of the Empire itself. Until the late fifteenth century the Habsburgs still

followed the German practice of dividing their territories between sons so Austria, Styria, Carniola, Carinthia and the Tyrol

- which were later to compose part of the Empire of Austria - were often ruled by different members of the family. In 1437,

Sigismond of Hungary and Bohemia died leaving an only daughter, to be succeeded by his son-in-law Albrecht V (of Habsburg),

Duke of Austria. Albrecht was now elected King of the Romans as Albrecht II but died before the coronation which would have

allowed him to take the Imperial style. While the Crowns of Bohemia and Hungary passed first to his short-lived son and then

to his son-in-law the King of Poland, in 1440 the Electors chose Albrecht's cousin and successor as ruler of Austria, Frederick

V of Styria (first Archduke of Austria in 1458), to be Emperor. The Imperial Crown remained the privilege of the Habsburgs

for the next three hundred years.

Frederick was the last Emperor to be crowned by the Pope in Rome and did much to consolidate the Habsburg possessions.

His great-grandson, the Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) united in his person the Imperial Crown, the hugely wealthy Duchies

of Burgundy and Brabant, the Duchy of Milan, the Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily and the Crown of Spain. The latter's brother

Ferdinand acquired by marriage the Crowns of Hungary and Bohemia in 1526. Unable to rule this vast Empire effectively, Charles

abdicated the Crown of Spain, the Italian possessions and the Burgundian inheritance to his only son, Philip II, in 1556,

and resigned the Imperial Crown to insure its inheritance by his brother Ferdinand, who was the first Habsburg to combine

the Imperial Crowns with those of Austria, Hungary and Bohemia.

The male line of the Habsburgs became extinct with the death of Charles VI in 1740. The

senior line, of Kings of Spain, had died out in the male line with the death of the unfortunate King Charles II in 1700 when

his Spanish possessions passed to his Bourbon great-nephew. The Spanish Netherlands (originally part of the Burgundian territories)

then passed to Austria, while Naples and Sicily were divided, to be temporarily reunited before being reacquired by the Bourbons

in 1734. Charles VI left an only daughter, Maria-Teresa, who had been married off to Francis, Duke of Lorraine, founding the

Habsburg-Lothringen dynasty which ruled in Austria, Hungary and Bohemia until 1918. Francis surrendered Lorraine (an Imperial

fief) to France as the temporary sovereign Duchy of the French King's father-in-law, the former King of Poland, from whom

it passed to France on his death in 1766. After a five year interregnum, during which time the Elector of Bavaria held the

Imperial Crown, Francis was elected Emperor. Following his death his eldest son, Joseph II, succeeded as the first Habsburg-Lothringen

Emperor

The Empire included

not only the territories of the nine Electors, but also more than three hundred small lay and ecclesiastical states whose

numbers fluctuated when male lines died out and families merged or divided. These petty rulers enjoyed limited "sovereignty"

over states which sometimes included no more than a few villages. Many of the Bishoprics governed small territories which

gave them the status of "immediate" [1] Imperial vassals. Some of the larger Abbeys and Convents enjoyed similar

status - their superiors composed the largest number of "elected" rulers, both men and women, Europe has ever seen,

even though only chosen by their fellow religious brothers or sisters. A smaller number of these "immediate" sovereigns

had the right to a seat in the Imperial Diet, a jealously guarded privilege which gave them some say in the legislative and

governmental affairs of the Empire and considerable prestige. In the middle of the seventeenth century there were forty-three

lay members and thirty-three ecclesiastical members of the Diet but their numbers expanded steadily until the Empire's collapse.

The Diet included the Electors, the rulers of the larger Duchies such as Wurtemberg, and Oldenburg, the smaller Saxon states

and Anhalt, and a larger number of Sovereign Princes and Sovereign Counts. Some of the ecclesiastical rulers enjoyed the status

of Princes, others only that of Counts and were ranked accordingly. The High Master of the Teutonic Knights, the Grand Prior

of Germany of the Order of Saint John (Malta), and the Master of the Knights of the Johanniter Order also had seats in the

Diet, ranking as Princes of the Empire.

The titles of Duke, Prince, Count, Baron, Knight and Noble of the Empire were conferred by Imperial patent. The vast

majority of the lower ranks never enjoyed any kind of sovereignty, however, having been elevated on the basis of services

to their superior lord, the Emperor himself, or by right of some territory they owned which was itself subject to an immediate

Imperial vassal. Most such conferrals were made at the request of the superior lord of the beneficiary - an Elector or Duke

perhaps, but the MarkGraf of Brandenburg as King in and then of Prussia was able to confer titles in his own right. Later

the Electors of Bavaria conferred titles as did some of the other greater Princes while many of the rulers of smaller states

had been invested with the right to confer nobility. Imperial Nobility and titles always passed by male succession, most titles

being inherited by all the male descendants and by females until marriage (or religious profession). Noble territories could

pass by female succession but use of the corresponding title would have to be confirmed in a new Imperial patent. Imperial

authority extended also to the Netherlands and Italy, and some of the higher North Italian titles (particularly that of Prince)

and Netherlandish titles were conferred by Imperial grant. The Imperial Viceroys, as rulers of the Netherlands, Milan and

Naples and Sicily also conferred titles but these were not Holy Roman Empire titles and their recipients did not rank as Reichsherren,

Reichsritter, Reichsfreiherr or Reichsgraf

In 1803-06 the principle states of the Empire were (in alphabetical order): (*= mediatized 1806-15) Anhalt-Dessau

(principality, Ducal title assumed 1807) Anhalt-Bernburg (ditto, Duke by Imperial Patent 1806, extinct and inherited by A-B-S)

Anhalt-Bernburg-Schaumburg (ditto, inherited Bernburg duchy, extinct 1863) Anhalt-Köthen (ditto, Ducal title assumed

1807, extinct 1847) Anhalt-Zerbst (actually amalgamated with senior line in 1793) (ditto) *Arenberg (Duchy, Sovereign Duke

of Dulmen 1803-1810) *Auersperg (Principality, Sovereign Count-Prince of Thengen to 1806, sold to Baden 1811) Austria (Archduchy,

then Empire 1804) Baden (Margravate, Grand Duchy in 1806) Bavaria and the Palatinate (the Palatinate was divided between adjacent

states, Electorate later King 1805) . seat in Diet, created Princes 1817) *Bentheim-Bentheim und Benthem-Steinfurt (Counts

with seat in Diet, created Princes 1817) *Bentinck (Counts, sov lords of Knyphausen u. Varel until 1806, recognised as mediatized

1845) Bohemia (Kingdom of, from 1804 the King was also Emperor of Austria) Brandenburg-Ansbach (Margravate, united with Prussia)

Brunswick-Wolfenbuttel (Duchy, extinct 1884, representation passed to Hanover) *Castell-Castell (Counts, created elevated

to Princely status1901) *Castell-Rüdenhausen (County, elevated to Princely status1901)

*Colloredo-Mansfeld (Principality) *Croy (Duchy, mediatized as Duke

of Dulmen in 1803, later acquired by Arenberg) *Dietrichstein zu Nicolsburg (Principality, 1858 titles passed to Mensdorf-Pouilly,

non-mediatised) *Erbach-Fürstenau (County) *Erbach-Erbach (County) *Erbach-Schönburg (County, later elevated to

Princely status) *Esterhazy von Galantha (Princes, mediatized as Count-Princes of Edelstetten 1803) *Fugger zu Kirchburg und

Weissenhorn (County) *Fugger von Glött (County, later elevated to Princely status) *Fugger von Babenhausen (Principality

1803) *Fulda (Principality, ruled by the Prince of Orange, Duke of Nassau) *Furstenberg-Stulingen (Principality) *Furstenberg

(Landgravate, extinct) *Giech (County, extinct 1938) *Harrach zu Rohrau und Thannhausen (County) Hesse (-Kassel) (Electorate

1803) Hesse-Philippsthal (Landgravate) Hesse-Rheinfels-Rothenburg (Landgravate) Hesse-Darmstadt (Landgravate, later Grand

Duchy) Hesse-Homburg (Landgravate) *Hohenlohe-Neuenstein (or Oehringen) (Principality) *Hohenlohe-Langenburg (Principality)

*Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen (Principality) *Hohenlohe-Kirchberg (Principality) *Hohenlohe-Bartenstein-Bartenstein (Principality)

*Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfurst (Principality) *Hohenlohe-Schillingsfurst (Principality, separated 1807) Hohenzollern-Hechingen

(Principality) Hohenzollern-Siegmaringen (Principality) (Schleswig-)Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg (Duchy) (Schleswig-)Holstein-Beck

(Duchy) (Schleswig-)Holstein-Glucksburg (Duchy, later of Schlesvig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glucksberg) (Schleswig-)Holstein-Oldenburg

(Duchy, later Grand Duchy of Oldenburg) *Isenburg-Birstein (Principality) *Isenburg und Budingen zu Philippseich(County, extinct

1920) *Isenburg und Budingen zu Budingen (County, later elevated to Princely status) *Isenburg und Budingen zu Wächtersbach

(County, later elevated to Princely status) *Kaunitz-Rietberg (Principality, extinct 1887) *Khevenhuller-Metsch (Principality)

*Kinsky (Principality) *Königsegg-Aulendorf (County) *Kuefstein (County) Liechtenstein (Principality) [2]Ligne (Principality,

lost Sovereignty in 1803 with sale of Princely-County of Edlestein) *Leiningen-Dachsburg (Principality) *Leiningen-Billigheim

(County, extinct 1900) *Leiningen-Neudenau (County, extinct 19..) *Leiningen-Westerburg-Alt-Leiningen (County, extinct 1929)

*Leyen und zu Hohengeroldseck (Principality, sovereign until 1815) Lippe-Detmold (Principality) *Lobkowicz (Principality)

*Loewenstein-Wertheim-Freudenberg (County, Principality from 1811) *Loewenstein-Wertheim-Rosenburg (Principality) *Looz und

Corswarem (Duchy, mediatized as Princes of Rheina-Wolbeck) Luxemburg (Duchy, later Grand Duchy)

Mecklemburg-Schwerin (Duchy, later Grand Duchy) Mecklemburg-Strelitz

(Duchy, later Grand Duchy) *Metternich-Winneburg (Principality, immediate 1803) Nassau-Usingen und Saarbruck (Duchy) Nassau-Saarbruck

(Duchy) Nassau-Weilburg (Duchy, extinct) Nassau-Diez (Duchy, merged with Weilburg until lost to Prussia 1867, acquired Luxemburg

1890) *Neipperg (County) *Neuwied (Principality, now Wied) *Oettingen-Spielburg (Principality) *Oettingen-Wallerstein (Principality)

*Ortenburg (County) *Palm (Principality) *Pappenheim (County) Platen-Hallermund (County and Lordship) *Plettenberg-Wittem

zu Mietingen (County, extinct 1813) Prussia (Kingdom) *Pückler-Muskau (Principality, extinct) *Pückler und Limpurg

(County, extinct 1892) *Pückler und Limpurg-Sontheim-Gaildorf (County) *Quadt-Wykradt und Isny (County, later elevated

to Princely status) *Rechburg und Rothenlöwen (County) *Rechteren-Limpurg-Speckfeld (County) Reuss-Plauen-Graitz (Principality)

Reuss-Lobenstein (Principality) *Rosenburg (Orsini and Rosenburg, Principality) *Salm-Salm (Principality) Mecklemburg-Schwerin

(Duchy, later Grand Duchy) Mecklemburg-Strelitz (Duchy, later Grand Duchy) *Metternich-Winneburg (Principality, immediate

1803) Nassau-Usingen und Saarbruck (Duchy) Nassau-Saarbruck (Duchy) Nassau-Weilburg (Duchy, extinct) Nassau-Diez (Duchy, merged

with Weilburg until lost to Prussia 1867, acquired Luxemburg 1890) *Neipperg (County) *Neuwied (Principality, now Wied) *Oettingen-Spielburg

(Principality) *Oettingen-Wallerstein (Principality) *Ortenburg (County) *Palm (Principality) *Pappenheim (County) Platen-Hallermund

(County and Lordship) *Plettenberg-Wittem zu Mietingen (County, extinct 1813) Prussia (Kingdom) *Pückler-Muskau (Principality,

extinct) *Pückler und Limpurg (County, extinct 1892) *Pückler und Limpurg-Sontheim-Gaildorf (County) *Quadt-Wykradt

und Isny (County, later elevated to Princely status) *Rechburg und Rothenlöwen (County) *Rechteren-Limpurg-Speckfeld

(County) Reuss-Plauen-Graitz (Principality) Reuss-Lobenstein (Principality) *Rosenburg (Orsini and Rosenburg, Principality)

*Salm-Salm (Principality)

*Sternberg-Manderscheid (County, extinct 1830) *Stolberg-Guedern (Principality, extinct) *Stolberg-Wernigerode

(County, later elevated to Princely status) *Stolberg-Stolberg (County, later elevated to Princely status) *Stolberg-Rossla

(County, later elevated to Princely status) *Thurn und Taxis (Principality) *Toerring-Jetenbach (County, now Toerring) *Toerring-Gutenzell

(County, extinct 1860) *Trauutmansdorf-Weinsburg (Principality) *Waldbott von Bassenheim (County) *Waldburg zu Wolfegg und

Waldsee (Principality) *Waldburg zu Zeil und Trauchburg (Principality) *Waldburg zu Zeil und Lustnau-Hohems (County) *Waldburg

zu Zeil und Wurzach (Principality) *Waldburg zu Zeil und Capustigall (County) *Waldburg zu Zeil und Pins (County) *Waldeck

und Pyrmont (Principality) *Waldeck-Limburg (extinct 1848) *Wallmoden-Gimborn (County, extinct) *Wied(-Runkel) (Principality,

extinct) *Windisch-Graetz (did not acquire this status until 1804, Principality) *Wurmbrand-Stuppach (County) *Wurtemburg

(Duchy, later Kingdom)

During

the years preceding and immediately following the collapse of the Empire there was considerable readjustment of territories

between states - mostly to the benefit of the larger states which were consolidated within contiguous borders - and of the

titles of their rulers. The Electors of Saxony, Wurtemberg and Bavaria became Kings, as did the Elector of Hannover following

the downfall of Napoleon, although as King of Great Britain he already enjoyed the royal style. The Kingdom of Westphalia

was created for Jerome Bonaparte after territories seized from Hannover, Brunswick and various ecclesiastical states on the

right bank of the Rhine but ceased to exist in 1814 when its lands were redistributed - those on the Rhine being given as

a prize to the King of Prussia.

The

Duchies of Mecklemburg-Schwerin, Mecklemburg-Strelitz, the Duchy of Oldenburg, the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar, and the Margravate

of Baden were elevated to the status of Grand Duchies as was the Landgravate of Hesse-Darmstadt. The Grand Duchy of Berg and

Cleves (given first to Murat and his wife Caroline Bonaparte, then Napoleon-Louis, the second son of Hortense de Beauharnais

and Louis Bonaparte), the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt (given first to Emmerich de Dalberg and then Eugène de Beauharnais),

and the Grand Duchy of Wurzburg (given to the Grand Duke of Tuscany as compensation for the loss of his Italian states) were

all created out of former ecclesiastical states or the territories of Napoleon's enemies. Their territories were redistributed

after 1814 and their rulers deposed, while the Grand Duke of Tuscany was restored to Florence. The Duchy of Luxembourg was

raised to the status of Grand Duchy and added to the Kingdom of the United Netherlands (until 1890 when it passed to the Duke

of Nassau), as were the former Austrian Netherlands, until they gained their independence as the Kingdom of the Belgians in

1830. Some states which survived the initial dissolution of the Empire, notably the Duchy of Arenberg which was actually enlarged

after 1806, and the Principality of Leyen, were unable to hold onto sovereignty in 1814, lacking the close family relationships

to the sovereigns of the victorious powers whose influence might have enabled them to hold their thrones.

The Imperial nobility enjoys a more elevated status

than the nobilities of the German successor states and, indeed, of the Italian states. The descendants of Italian Holy Roman

Empire titles have formed an Association to which every male line descendant of someone ennobled by Imperial Patent is entitled

to belong. The Principality of Liechtenstein has also claimed to be able to confirm the succession to Imperial titles and

has confirmed the right of a Spanish nobleman to be heir to such a title, for purposes of the Spanish law requiring the successor

state to confirm that the claimant to a particular title is in fact the heir. Thus there is a remaining jurisdiction, even

though no Imperial titles have been conferred since 1806.