|

Nobility of the World Volume VIII - Poland Szlachta was the noble class in

the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (which were united in 1569 and then became the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth) and the increasingly polonized territories under their control (such as Ducal Prussia or

the Ruthenian lands). The nobility arose in the late Middle Ages. Traditionally, its members were owners of landed

property, often in the form of folwarks. The nobility enjoyed substantial and almost unrivaled political privileges until

the late 18th century. Their sovereignty was ended in 1795 by the Partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Then, until 1918 their legal status was dependent on policies of the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia or

the Habsburg Monarchy. In the Second Polish Republic the privileges of the nobility were

lawfully abolished by the March Constitution in 1921 and have not been re-granted by any later Polish law.

History and

Etymology The

Polish term "szlachta" designates the formalized, hereditary noble class. In official Latin documents the oldCommonwealth hereditary

szlachta is referred to as "nobilitas" and is equivalent to the English nobility. There used to be a widespread

misconception to translate "szlachta" as "gentry", because some nobles were poor. Some were even poorer

than the non-noble gentry that declined with the 'second serfdom' and re-emerged after thePartitions. Some would

even become tenants to the gentry but still kept their constitutional superiority. But it's not wealth or lifestyle (as with

the gentry) but a hereditary legal status of a nobleman that makes you one. A specific nobleman was called a "szlachcic",

and a noblewoman, a "szlachcianka." "Szlachta" derives from the Old German word "slahta" (now

"(Adels) Geschlecht", "(noble) family"), much as many other Polish words pertaining to the nobility derive

from German words - e.g., the Polish "rycerz" ("knight", cognate of the German "Ritter") and

the Polish "herb" ("coat of arms", from the German "Erbe", "heritage"). Poles of the

17th century assumed that "szlachta" was from the German "schlachten" ("to slaughter" or "to

butcher"); also suggestive is the German "Schlacht" ("battle"). Early Polish historians thought the

term may have derived from the name of the legendary proto-Polish chief, Lech, mentioned in Polish and Czech writings. "Šlėkta" is

a derivative from a Polish term used in the Lithuanian language having more or less the same meaning usually

with a negative nuance. Kindred terms that might be applied to an early Polish nobleman were "rycerz" (from German

Ritter, "knight"), the Latin "nobilis" ("noble"; plural: "nobiles") and

"możny" ("magnate", "oligarch"; plural: "możni"). Some powerful Polish nobles

were referred to as "magnates" (Polish singular: "magnat", plural: "magnaci"). It has to be

remembered however, that not all knights were nobles. Today the word szlachta in the Polish language denotes any noble class in the world. In

broadest meaning, it can also denote some non-hereditary honorary knighthoods granted today by some European monarchs. Even

some 19th century non-noble landed gentry would be called szlachta by courtesy or error as they owned manorial estates but

were not noble by birth. In the narrow sense it denotes the old-Commonwealth nobility.

The Origins of Polish Nobility

The Polish

nobility probably derived from a Slavic warrior class, forming a distinct element within the ancient Polonic

tribal groupings. This is uncertain, however, as there is little surviving documentation on the early history of Poland, or

of the movements of the Slavonic people into what became the territory so designated. The szlachta themselves claimed descent

from the Sarmatians (see paragraph 2.2 below) who came to Europe in the 5th century C.E. Around the 14th century,

there was little difference between knights and the szlachta in Poland, apart from legal and economic. Members of the szlachta

had the personal obligation to defend the country (pospolite ruszenie), thereby becoming the kingdom's privileged social class. Concerning the early Polish tribes,

geography contributed to long-standing traditions. The Polish tribes were internalized and organized around a unifying religious

cult, governed by the wiec, an assembly of free tribesmen. Later, when safety required power to be consolidated, an elected

prince was chosen to govern. The tribes were ruled by clans (ród) consisting of people related by blood and descending from a common ancestor,

giving the ród/clan a highly developed sense of solidarity. (See gens.) The starosta (or starszyna)

had judicial and military power over the ród/clan, although this power was often exercised with an assembly of elders.

Strongholds called grόd were built where the religious cult was powerful, where trials were conducted, and

where clans gathered in the face of danger. The opole was the territory occupied by a single tribe. (Manteuffel 1982, p. 44). Before going deeper into the history

of Polish nobility, it is important to note use of the English word "knight", which can be misleading as it leads

to inevitable comparisons with the British gentry. In comparison, the Polish nobility was a "power elite" caste,

not a social class. The paramount principle of Polish nobility was that it was hereditary. Mieszko I of Poland (c. 935 - 25 May 992) utilized

an elite knightly retinue from his army, which he depended upon for success in uniting the Lekhitic tribes and preserving

the unity of his state. Documented proof exists of Mieszko I's successors utilizing such a retinue, too. Another class of knights were granted

land by the prince, allowing them to serve the prince militarily. A Polish nobleman living at this time before the 15th century

was referred to as a "rycerz", very roughly equivalent to the English "knight", the critical difference

being the status of "rycerz" was strictly hereditary; the class of all such individuals was known as the "rycerstwo".

Representing the wealthier families of Poland and itinerant knights from abroad seeking their fortunes, this other class of

rycerstwo, which became the szlachta/nobility ("szlachta" becomes the proper term for Polish nobility beginning

about the 15th century), gradually formed apart from Mieszko I's and his successors' elite retinues. This rycerstwo/nobility

obtained more privileges granting them favored status. They were absolved from particular burdens and obligations under ducal

law, resulting in the belief only rycerstwo (those combining military prowess with high/noble birth) could serve as officials

in state administration. Select rycerstwo were distinguished above the other rycerstwo, because they descended from past tribal dynasties,

or because early Piasts' endowments made them select beneficiaries. These rycerstwo of great wealth were called

możni (Magnates). Socially they were not a distinct class from the rycerstwo they originated from and to which they would

return were their wealth lost. (Manteuffel 1982, pp. 148-149). The Period of Division, A.D., 1138 - A.D., 1314, nearly 200 years of feudal fragmentation,

when Bolesław III divided Poland among his sons, began the social structure allegedly separating great landowning

feudal nobles (możni/Magnates, both ecclesiastical and lay) from the rycerstwo they originated from. The prior social

structure was one of Polish tribes united into the historic Polish nation under a state ruled by the Piast dynasty, this

dynasty appearing circa 850 A.D. Some możni (Magnates) descending from past tribal dynasties regarded themselves as co-proprietors

of Piast realms, even though the Piasts attempted to deprive them of their independence. These możni (Magnates) constantly

sought to undermine princely authority. In Gall Anonym's chronicle, there is noted the nobility's alarm when the Palatine Sieciech

"elevated those of a lower class over those who were noble born" entrusting them with state offices.

The Lithuanian Nobility

In Lithuania

Propria, Samogitia and Prussia, prior to the creation of the Kingdom of Lithuania by Mindaugas,

nobles were called 'bajorai' and the higher nobility 'kunigai' or 'kunigaikščiai' (dukes). They were the established

local leaders and warlords. During the development of the state they gradually became subordinated to higher dukes, and later

to the King of Lithuania. After the Union of Horodło the Lithuanian nobility acquired equal status with the Polish

szlachta, and over time began to become more and more polonized, although they did preserve their national consciousness,

and in most cases recognition of their Lithuanian family roots. In the 16th century some of the Lithuanian nobility erroneously

claimed that they were of Roman extraction, and the Lithuanian language was just a morphed Latin language. The process of polonization took

place over a lengthy period of time. At first only the highest members of the nobility were involved, although gradually a

wider group of the population was affected. The major effects on the lesser Lithuanian nobility took place after various sanctions

were imposed by the Russian Empire such as removing Lithuania from the names of the Gubernyas few years after the November

Uprising. After the January Uprising the sanctions went further, and Russian officials announced that "Lithuanians

are Russians seduced by Poles and Catholicism" and began to intensify russification, and to ban the printing

of books in the Lithuanian language.  The Ruthenian Nobility

In Ruthenia (Ukraine) the

nobility gradually gravitated its loyalty towards the multicultural and multilingualGrand Duchy of Lithuania after the

principalities of Halych and Volhynia became a part of it. Many noble Ruthenian families intermarried

with Lithuanian ones. The Orthodox nobles' rights were nominally equal to those enjoyed by Polish and Lithuanian nobility,

but there was a cultural pressure to convert to Catholicism, that was greatly eased in 1596 by the Union of Brest. See

for example careers of Senator Adam Kisiel and Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki.

Szlachta's Rise to Power Nobles were born into a noble

family, adopted by a noble family (this was abolished in 1633) or ennobled by a king or Sejm for various

reasons (bravery in combat, service to the state, etc. - yet this was the rarest means of gaining noble status). Many nobles

were, in actuality, really usurpers, being commoners, who moved into another part of the country and falsely pretended to

noble status. Hundreds of such false nobles were denounced by Hieronim Nekanda Trepka in his Liber generationis

plebeanorium (or Liber chamorum) in the first half of 16th century. The law forbade non-nobles from owning nobility-estates

and promised the estate to the denouncer. Trepka was an impoverished nobleman who lived a townsman life and collected hundreds

of such stories hoping to take over any of such estates. It doesn't seem he ever succeeded in proving one at the court. Many

sejms issued decrees over the centuries in an attempt to resolve this issue, but with little success. It is unknown what percentage

of the Polish nobility came from the 'lower' orders of society, but most historians agree that nobles of such base origins

formed a 'significant' element of the szlachta. The Polish nobility enjoyed many rights that were not available to the noble classes of

other countries and, typically, each new monarch conceded them further privileges. Those privileges became the basis

of the Golden Liberty in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Despite having a king, Poland was called the nobility'sCommonwealth because the

king was elected by all interested members of hereditary nobility and Poland was considered to be the property of this

class, not of the king or the ruling dynasty. This state of affairs grew up in part because of the extinction of the

male-line descendants of the old royal dynasty (first the Piasts, then the Jagiellons), and the selection by the

nobility of the Polish king from among the dynasty's female-line descendants. Branicki,holding hetman's buława. Poland's successive kings granted

privileges to the nobility at the time of their election to the throne (the privileges being specified in the king-elect's Pacta

conventa) and at other times in exchange for ad hoc permission to raise an extraordinary tax or a pospolite

ruszenie Poland's nobility thus accumulated a growing array of privileges and immunities, In 1355 in Buda King Casimir

III the Great (Kazimierz Wielki) issued the first country-wide privilege for the nobility, in exchange for their agreement

that in the lack of Kazimierz male heirs, the throne would pass to his nephew, Louis I of Hungary. He decreed

that the nobility would no longer be required to pay 'extraordinary'taxes, or pay with their own funds for military expeditions

outside Poland. He also promised that during travels of the royal court, the king and the court would pay for all expenses,

instead of using facilities of local nobility. In 1374 King Louis of Hungary approved the Privilege of Koszyce (Polish:

"przywilej koszycki" or "ugoda koszycka") in Košice in order to guarantee the Polish

throne for his daughter Jadwiga. He broadened the definition of who was a member of the nobility and exempted the entire

class from all but one tax (łanowy, which was limited to 2 groszefrom łan (an old measure of land size)). In

addition, the King's right to raise taxes was abolished; no new taxes could be raised without the agreement of the nobility.

Henceforth, also, district offices (Polish: "urzędy ziemskie") were reserved exclusively for local

nobility, as the Privilege of Koszyce forbade the king to grant official posts and major Polish castles to foreign knights.

Finally, this privilege obliged the King to pay indemnities to nobles injured or taken captive during a war outside

Polish borders. In

1422 King Władysław II Jagiełło by the Privilege of Czerwińsk (Polish: "przywilej

czerwiński") established the inviolability of nobles' property (their estates could not be confiscated except upon

a court verdict) and ceded some jurisdiction over fiscal policy to the Royal Council (later, the Senat),

including the right to mint coinage. In 1430 with the Privileges of Jedlnia, confirmed at Kraków in 1433

(Polish: "przywileje jedlneńsko-krakowskie"), based partially on his earlier Brześć Kujawski privilege

(April 25, 1425), King Władysław II Jagiełło granted the nobility a guarantee against arbitrary arrest,

similar to the English Magna Carta's Habeas corpus, known from its own Latin name as "neminem captivabimus (nisi

jure victum)." Henceforth no member of the nobility could be imprisoned without a warrant from a competent court of justice:

the king could neither punish nor imprison any noble at his whim. King Władysław's quid pro quo for this

boon was the nobles' guarantee that his throne would be inherited by one of his sons (who would be bound to honour the privileges

theretofore granted to the nobility). On May 2, 1447 the same king issued the Wilno Privilege which gave the Lithuanian boyars the

same rights as those possessed by the Polish szlachta. In 1454 King Kazimierz IV Jagiellon granted the Nieszawa Statutes (Polish:

"statuty cerkwicko-nieszawskie"), clarifying the legal basis of voivodship sejmiks (local parliaments).

The king could promulgate new laws, raise taxes, or call for a levée en masse (pospolite ruszenie)

only with the consent of the sejmiks, and the nobility were protected from judicial abuses. The Nieszawa Statutes also curbed

the power of the magnates, as the Sejm (national parliament) received the right to elect many officials, including judges, voivods and castellans.

These privileges were demanded by the szlachta as a compensation for their participation in the Thirteen Years' War. The first "free election"

(Polish: "wolna elekcja") of a king took place in 1492. (To be sure, some earlier Polish kings had been elected

with help from bodies such as that which put Casimir II on the throne, thereby setting a precedent for free elections.)

Only senators voted in the 1492 free election, which was won by Jan I Olbracht. For the duration of the Jagiellonian

Dynasty, only members of that royal family were considered for election; later, there would be no restrictions on the choice

of candidates. In 1493 the national parliament,

the Sejm, began meeting every two years at Piotrków. It comprised two chambers: - a Senate of 81 bishops and other dignitaries; and

- a Chamber of Envoys of 54 envoys (in Polish, "envoy" is "poseł")

representing their respective Lands.

The numbers of senators and envoys later increased. On April 26, 1496 King Jan I Olbracht granted the Privilege of Piotrków (Polish:

"Przywilej piotrkowski", "konstytucja piotrkowska" or "statuty piotrkowskie"), increasing the

nobility's feudal power over serfs. It bound the peasant to the land, as only one son (not the eldest) was

permitted to leave the village; townsfolk (Polish: "mieszczaństwo") were prohibited from owning land; and positions

in the Church hierarchy could be given only to nobles. On 23 October 1501, at Mielnik Polish-Lithuanian Union was reformed at the Union

of Mielnik (Polish: unia mielnicka, unia piotrkowsko-mielnicka). It was there that the tradition of the coronation

Sejm (Polish: "Sejm koronacyjny") was founded. Once again the middle nobility (middle in wealth, not in rank)

attempted to reduce the power of the magnates with a law that made them impeachable before the Senate for malfeasance.

However the Act of Mielno (Polish: Przywilej mielnicki) of 25 October did more to strengthen the magnate dominated Senate

of Poland then the lesser nobility. The nobles were conceded the right to refuse to obey the King or his representatives-in

the Latin, "non praestanda oboedientia"--and to form confederations, an armed rebellion against the king or

state officers if the nobles thought that the law or their legitimate privileges were being infringed. On 3 May 1505 King Aleksander

I Jagiellon granted the Act of "Nihil novi nisi commune consensu" (Latin: "I accept nothing new except

by common consent"). This forbade the king to pass any new law without the consent of the representatives of the nobility,

in Sejm and Senat assembled, and thus greatly strengthened the nobility's political position. Basically, this act transferred

legislative power from the king to the Sejm. This date commonly marks the beginning of the First Rzeczpospolita, the

period of a szlachta-run "Commonwealth". In 1520 the Act of Bydgoszcz granted the Sejm the right to convene every four

years, with or without the king's permission. About that time the "executionist movement" (Polish: "egzekucja

praw"--"execution of the laws") began to take form. Its members would seek to curb the power of the magnates

at the Sejm and to strengthen the power of king and country. In 1562 at the Sejm in Piotrków they would force the magnates

to return many leasedcrown lands to the king, and the king to create a standing army (wojsko kwarciane). One of the most

famous members of this movement was Jan Zamoyski. After his death in 1605, the movement lost its political force. Until the death of Zygmunt II

August, the last king of the Jagiellonian dynasty, monarchs could only be elected from within the royal family.

However, starting from 1573, practically any Polish noble or foreigner of royal blood could become a Polish-Lithuanian monarch.

Every newly elected king was supposed to sign two documents - thePacta conventa ("agreed pacts") - a confirmation

of the king's pre-election promises, and Henrican articles(artykuły henrykowskie, named after the first freely elected

king, Henry of Valois). The latter document served as a virtual Polish constitution and contained the basic laws of the

Commonwealth: - Free election of kings;

- Religious tolerance;

- The Diet to

be gathered every two years;

- Foreign policy controlled

by the Diet;

- A royal advisory council chosen by the

Diet;

- Official posts restricted to Polish and Lithuanian

nobles;

- Taxes and monopolies set up by the Diet only;

- Nobles' right to disobey the king should he break any of these laws.

In 1578 king Stefan Batory created

the Crown Tribunal in order to reduce the enormous pressure on the Royal Court. This placed much of the monarch's

juridical power in the hands of the elected szlachta deputies, further strengthening the nobility class. In 1581 the Crown

Tribunal was joined by a counterpart in Lithuania, theLithuanian Tribunal.  Transformation into AristocracyFor many centuries, wealthy and powerful

members of the szlachta sought to gain legal privileges over their peers. Few szlachta were wealthy enough to be known as

magnates (karmazyni - the "Crimsons", from the crimson colour of their boots). A proper magnate should be able to

trace noble ancestors back for many generations and own at least 20 villages or estates. He should also hold a major office

in the Commonwealth. Some historians estimate the number of magnates as 1% of the number of szlachta. Out of approx. one million szlachta,

tens of thousands of families, only 200-300 persons could be classed as great magnates with country-wide possessions and influence,

and 30-40 of them could be viewed as those with significant impact on Poland's politics. Magnates often received gifts from monarchs, which significantly

increased their wealth. Often, those gifts were only temporary leases, which the magnates never returned (in 16th century,

the anti-magnate opposition among szlachta was known as the ruch egzekucji praw - movement for execution of the laws - which

demanded that all such possessions are returned to their proper owner, the king). One of the most important victories of the magnates was

the late 16th century right to create ordynacja's (similar tomajorats), which ensured that a family which gained wealth

and power could more easily preserve this. Ordynacje's of families of Radziwiłłs, Zamoyskis, Potockis or Lubomirskis often

rivalled the estates of the king and were important power bases for the magnates. Loss of influence by szlachtaThe sovereignty of szlachta was ended in 1795 by the Partitions of Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth. Then, until1918 their legal status dependent on policies of: Russian Empire, Kingdom of Prussia or Habsburg

Monarchy. InSecond Polish Republic the privileges of the nobility were lawfully abolished by the March Constitution in 1921 and

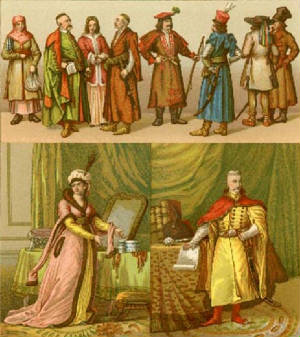

as such not granted by any future Polish law. Szlachta culture The Polish nobility differed in many respects from the nobility of other countries. The

most important difference was that, while in most European countries the nobility lost power as the ruler strove for absolute

monarchy, in Poland the reverse process occurred: the nobility actually gained power at the expense of the king, and the political

system evolved into anoligarchy. Poland's nobility were also more numerous than those of all other European countries, constituting some 10%

- 12% of the total population of historic Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth also some 10% - 12% among ethnic Poleson

ethnic Polish lands (part of Commonwealth), but up to 25% of all Poles worldwide

(szlachta could dispose more of resources to travels and/or conquering), while in some poorer regions (e.g. Mazowsze,

the area centred onWarsaw) nearly 30%. However, according to szlachta comprised around 8% of the total population in 1791

(up from 6.6% in the 16th century), and no more than 16% of the Roman Catholic (mostly ethnically Polish) population. It should

be noted, though, that Polish szlachta usually incorporated most local nobility from the areas that were absorbed by Poland-Lithuania

(Ruthenian boyars, Livonian nobles, etc.) By contrast, the nobilities of other European countries, except for Spain, amounted

to a mere 1-3%, however the era of sovereign rules of Polish nobility ended earlier then in other countries (excluding France)

yet in 1795 (see: Partitions of Poland), since then their legitimation and future fate depended on legislature

and procedures of Russian Empire, Kingdom of Prussia orHabsburg Monarchy. Gradually their privileges were under

further limitations to be completely dissolved byMarch Constitution of Poland in 1921. There were a number of avenues to upward social mobility

and the achievement of nobility. Poland's nobility was not a rigidly exclusive, closed class. Many low-born individuals, including townsfolk, peasants and Jews,

could and did rise in Polish society up to official ennoblement. Thus Poland's noble class was more stable than those

of other countries, and so was spared the societal tensions and eventual disintegration that characterised the French

Revolution. Each szlachcic had enormous influence over the country's politics, in some ways even greater than what is enjoyed

by the citizens of modern democratic countries. Between 1652 and 1791, any nobleman could nullify all the proceedings of a

given sejmsejmik (Commonwealth local parliament) by exercising his individual right of liberum veto (Latin

for "I do not allow"), except in the case of a confederated sejm or confederated sejmik. (Commonwealth

parliament) or All

children of the Polish nobility inherited their noble status from a noble mother and father. Any individual could attain ennoblement

(nobilitacja) for special services to the state. A foreign noble might be naturalised as a Polish noble (Polish: "indygenat")

by the Polish king (later, from 1641, only by a general sejm). In theory at least, all Polish noblemen were social equals. Also in theory they were legal

peers. Those who held 'real power' dignities were more privileged but these dignities were not hereditary. Those who held

honorary dignities were higher in 'ritual' hierarchy but these dignities were also granted for a lifetime. Some tenancies

became hereditary and went with both privilege and titles. Nobles who were not direct barons of the Crown but held land from

other lords were only peers "de iure". The poorest enjoyed the same rights as the wealthiest magnate. The exceptions

were a few symbolically privileged families such as the Radziwiłł, Lubomirski and Czartoryski, who sported

honorary aristocratic titles recognized in Poland or received from foreign courts, such as "Prince" or "Count."

(see also The Princely Houses of Poland). All other szlachta simply addressed each other by their given name or as "Sir

Brother" (Panie bracie) or the feminine equivalent. The other forms of address would be "Illustrious and Magnificent

Lord", "Magnificent Lord", "Generous Lord" or "Noble Lord" (in decreasing order) or simply

"His/Her Grace Lord/Lady XYZ". Hetman Stefan Czarniecki in crimson bekiesza. Holds buława in right hand.

Note crimson boots (buty karmazynowe), a sign of wealth

and high status. The crimson color

worn by wealthy szlachta prompted the magnates' nickname,

"karmazyni" - "the crimson ones." According to their financial standing, the nobility were in common speech divided into: - magnates: the wealthiest class; owners of vast lands, towns, many villages, thousands of

peasants

- middle nobility (średnia szlachta):

owners of one of more villages, often having some official titles or Envoys from the local Land Assemblies to the General

Assembly,

- petty nobility (drobna szlachta), owners

of a part of a village or owning no land at all, often referred to by a variety of colourful Polish terms such as:

- szaraczkowa - grey nobility, from their grey, woollen, uncoloured zupans

- okoliczna - local nobility, similar to zaściankowa

- zagrodowa - from zagroda, a farm, often little different from a peasant's dwelling

- zagonowa - from zagon, a small unit of land measure, hide nobility

- cząstkowa - partial, owners of only part of a single village

- panek - little pan (i.e. lordling), term used in Kaszuby, the Kashubian region, also

one of the legal terms for legally separated lower nobility in late medieval and early modern Poland

- hreczkosiej - buckwheat sowers - those who had to work their fields themselves.

- zaściankowa - from zaścianek, a name for plural nobility settlement, neighbourhood

nobility. Just like hreczkosiej, zaściankowa nobility would have no peasants.

- brukowa - cobble nobility, for those living in towns like townsfolk

- gołota - naked nobility, i.e. the landless. Gołota szlachta would be considered

the 'lowest of the high'.

Note that Polish landed gentry (ziemianie or ziemiaństwo) was composed of any nobility that

owned lands: thus of course the magnates, the middle nobility and that lesser nobility that had at least part of the village.

As manorial lordships were also opened to burgesses of certain privileged royal cities, not all landed gentry had a hereditary

title of nobility. Polish

Heraldry Coats

of arms were very important to the Polish nobility. It is notable, that the Polish heraldic system evolved separately

from its western counterparts and differed in many ways from the heraldry of other European countries. The most notable difference is that,

contrary to other European heraldic systems, most families sharing origin would also share a coat-of-arms. They would also

share arms with families adopted into the clan (these would often have their arms officially altered upon ennoblement). Sometimes

unrelated families would be falsely attributed to the clan on the basis of similarity of arms. Also often noble families claimed

inaccurate clan membership. Logically, the number of coats of arms in this system was rather low and did not exceed 200 in

late Middle Ages (40.000 in late XVIII century). Also, the tradition of differentiating between the coat of arms proper and a lozenge granted

to women did not develop in Poland. Usually men inherited the coat of arms from their fathers. Also, the brisure was

rarely used. Sarmatism The szlachta's prevalent mentality

and ideology were manifested in "Sarmatism", a name derived fromscientifically unproved myth about

szlachta origin from powerful ancient nation of Sarmatians. This belief system became an important part of szlachta culture

and affected all aspects of their lives. It popularised by poets enshrined traditional village life, peace and pacifism; also

oriental-style apparel (the żupan, kontusz, sukmana, pas kontuszowy, delia); and made the scimitar-like szabla,

too, a near-obligatory item of everyday szlachta apparel. Sarmatism served to integrate the multi-ethnic nobility as it created

an almost nationalistic sense of unity and pride in the szlachta's "Golden Liberty" (złota wolność).

Knowledge of Latin was widespread, and most szlachta freely mixed Polish and Latin vocabulary (the latter, "macaronisms"

- from "macaroni") in everyday conversation. In its early, idealistic form, Sarmatism seemed like a salutary cultural movement: it fostered

religious faith, honesty, national pride, courage, equality and freedom. Late Sarmatism turned belief into bigotry, honesty

into political naiveté, pride into arrogance, courage into stubbornness, equality and freedom within the szlachta class

into dissension and anarchy. The Religious Beliefs of The Polish Nobility

Prior to the Reformation, the Polish nobility were mostly either Roman

Catholic or Orthodox with a small group ofMuslims. Many families, however, soon adopted the Reformed faiths.

After the Counter-Reformation, when theRoman Catholic ChurchPoland, the nobility became almost exclusively Catholic,

despite the fact that Roman Catholicism was not the majority religion in Commonwealth (the Catholic and Orthodox churches

each accounted for some 40% of regained power in all citizensJacob Frank joined the ranks

of Jewish-descended Polish gentry. population, with the remaining 20% being Jews or members of Protestant denominations).

In the 18th century, many followers of Jacob Frank joined the ranks of Jewish-descended Polish

gentry. Although Jewish ethnicity wasn't usually a pretext to block or deprive

of noble status, however some laws required religious convert from Judaism to Christianity

(see: Neophyte) to be ennobled.

The Ennoblement In Kingdom

of Poland The

increase of number of Polish nobility by trustworthy ennoblements is proportionally minimal (since XIV

century). In the Kingdom of Poland and later in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, ennoblement (nobilitacja)

meant an individual's joining the szlachta (Polish nobility). At first it was granted by monarch, since late XVI century

by the sejm that gave the ennobled person a coat of arms. Often that person could join an

existing noble szlachta family with their own coat of arms. According to heraldic sources total number of trustworthy

ennoblements issued since XIV century until late XVIII century, is estimated as about 800 (which gives probably average of

about two ennoblements per year, trivia: some above 0.000 000 14 - 0.000 001 of historical population,

compare: historical demography of Poland). Late XVIII century is time of short loosening of ennoblements

policy, which can be explained in terms of sudden collapse of Commonwealth and sudden need of soldiers (see: Partitions

of Poland, King Stanisław August Poniatowski). The Total Number of Ennoblements Estimation according to heraldic sources 1 600 (half o which constitute, performed

in final years of the state collapse "sudden ennoblements" of late XVIII century) is a total

estimated number of all trustworthy ennoblements in history of Kingdom of Poland and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth since

XIV century. Polish Types of Ennoblement - Skartabelat - introduced by pacta conventa of XVII century, ennoblement into

a sort of lower nobility. Skartabels could not hold public offices or be members of the Sejm. After three generations in noble

ranks these families would "mature" to peerage.

- Adopcja

herbowa - old way of ennoblement, popular in XV century, connected with adoption into an existing noble clan by a powerful

lord, abolished in XVII century

Similar

Terms - Indygenat - recognition of foreign

noble status. A foreign noble, after indygenat, received all privileges of a Polish szlachcic. In Polish history, 413 foreign

noble families were recognized. From XVI century this was done by the King and SejmSejm only. (Polish parliament),

since XVII century it was done by

- "secret ennoblement"

of questionable legal status, opposed/not recognized by szlachta; by monarch without

required by law approval of the sejm.

In The Grand Duchy of Lithuania In the late 14th century, in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Vytautas the Great reformed

the Grand Duchy's army: instead of calling all men to arms, he created forces comprising professional warriors-bajorai ("nobles";

see thecognate "boyar"). As there were not enough nobles, Vytautas trained suitable men, relieving them of

labor on the land and of other duties; for their military service to the Grand Duke, they were granted land that

was worked by hired men (veldams). The newly-formed noble families generally took up, as their family names, the Lithuanianpagan given

names of their ennobled ancestors; this was the case with the Goštautai, Radvilos, Astikai, Kęsgailosand

others. These families were granted their coats of armsUnion of Horodlo (1413). under the In 1506, KingSigismund

I the Old confirmed the position of the Lithuanian Council of Lords in state politics and limited entry into

the nobility. The

List of Szlachta The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was a semi-confederal and semi-federal monarchic republic

comprising the Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania, from 1569 until 1795. The head of state was

an electedmonarch. The Commonwealth's dominant social class was the nobility. This article chiefly lists

the nobility'smagnate segment (the wealthier nobility), as they were the most prominent, famous and notable.

These families would receive non-hereditary 'central' and Land dignities and titles under the Commonwealth law that

forbade (with minor exceptions) any hereditary legal distinctions within the peerage. They would later be 'approximated' to

honorary hereditary titles in the Partition period with little real-power privileges but would still be venerated

among the Polish upper class and the rest of the society as 'senatorial', 'palatinal', 'castellanial' or "dignitarial'

families."Szlachta"

is the proper term for Polish nobility beginning about the 15th century. Most powerful members of szlachta were

known as magnates ("magnaci" or the "magnateria" class). A Polish nobleman

who lived earlier is referred to as a "rycerz" ("knight"); the class of all such individuals

is the "rycerstwo" (the "chivalry" class). Most powerful members of "rycerstwo"

were known as "możnowładzcy" (the "moznowładztwo" class). By Family Below is a list of most important Polish noble (szlachta)

families. The families listed are the famous magnatesfamilies - ones that had accumulated great wealth and political

power, generally preserved across several centuries. Please note that this list is not intended to be a comprehensive list

of all szlachta families. For the list of lesser known but still notable Polish noble families, see the corresponding

category. All names are given first in

the singular, then (parenthetically) in the plural. * Chodkiewicz (Chodkiewiczowie)

* Czartoryski (Czartoryscy)

* Lanckoroński (Lanckorońscy)

* Lubomirski (Lubomirscy)

* Mielzynski (Mielzynscy) .

* Ogiński (Ogińscy) * Ostrogski (Ostrogscy)

* Ostroróg (Ostrorogowie)

* Pac (Pacowie)

*

Poniatowski (Poniatowscy)

* Potocki (Potoccy) * Radziwiłł (Radziwiłłowie)

* Sapieha (Sapiehowie)

* Sanguszko (Sanguszkowie)

*

Tarnowski (Tarnowscy) * Tęczyński

(Tęczyńscy)

* Tyszkiewicz (Tyszkiewiczowie)

* Wiśniowiecki (Wiśniowieccy)

* Zamoysk (Zamoyscy) By The Year of Birth Listed below are important members of the szlachta of Poland and

the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, by century and year of birth. In many cases, birth year is uncertain or unknown.

During the Commonwealth, most people-including szlachta-paid little attention to their birthdates. The 15th Century Polish Nobility - Jan "Scibor" Taczanowski, 15th century, voivode of Łęczyca c.

1437

- Peter Hussakowski (Usakowski) 1448, Nobleman

- Jan Tarnowski, 1488-1561, hetman

- Jan Lubrański, 1456-1520, bishop

- Jan Łaski, 1456-1531, primate, archbishop

- Mikołaj

Kamieniecki, 1460-1515, hetman

- Konstanty Ostrogski,

1460-1530, hetman

- Krzysztof Szydłowiecki, 1467-1532,

chancellor

- Michał Gliński, 1470-1534, prince

- Jan Feliks "Szram" Tarnowski, 1471-1507, castellan, voivode

- Jan Stawicki, 1473-1510, voivode, starost of Didnia

- Jan "Ciężki" Tarnowski, 1479-1527, castellan, starost

- Tiedemann Giese, 1480-1560, bishop

- Barbara Kola, 1480-1560

- Jerzy Radziwiłł,

1480-1541, hetman, voivode, castellan, marshal

- Jan Tęczyński, 1485-1553, Court Marshall

- Piotr Gamrat, 1487-1545, bishop

- Stanisław

Kostka, 1487-1555, castellan, podskarbi

- Jan Łaski,

1499-1560, philosopher

- Tomasz Łaźniński,

15th century (or earlier)-?

- Maciej Zamoyski, 15th

century-?

- Jan Zamoyski, 15th century-16th century

- Florian Zamoyski, 15th century-1510

- Barbara Kiszka, 15th century-1513

- Mikołaj

Firlej, 15th century-1526, voivode, hetman

- Andrzej

Tarło, 15th century-1531, chorąży

- Feliks

Zamoyski, 15th century-1535, voivode

- Jan Tarło,

15th century-1550, krajczy, podczaszy, cześnik

- Piotr

Firlej, 15th century-1553, voivode

- Mikołaj Mielecki,

15th century-1585, hetman, voivode

The 16th century Polish Nobility - Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski (ca. 1503-1572) scholar, humanist and theologian

- Mikołaj Rej, 1505-1568, writer

- Stanisław Odrowąż, 1509-1545, castellan, voivode

- Jerzy Jazłowiecki, 1510-1575, hetman

- Marcin Kromer, 1512-1589, Prince-Bishop

- Mikołaj

"the Red" Radziwiłł, 1512-1584, hetman, kanclerz (chancellor)

- Mikołaj "the Black" Radziwiłł, 1515-1565, marshal, chancellor, palatine

- Hieronim Jarosz Sieniawski, 1516-1579, voivode

- Stanisław Zamoyski, 1519-1572, castellan

- Barbara Radziwiłł, 1520-1550, queen

- Jan Firlej, 1521-1574, marshall, starost

- Konstanty

Wasyl Ostrogski, 1526-1608, voivode

- Jan Tarło,

1527-1587, castellan, voivode

- Michał Wiśniowiecki,

1529-1584, castellan

- Jan Kostka, 1529-1581, voivode

- Grzegorz Branicki, c.1534-1595, łowczy of Kraków, starost of Niepołomice

- Zofia Tarnowska, 1534-1570

- Jan Krzysztof Tarnowski, 1537-1567, castellan

- Sebastian

Lubomirski, 1539-1613, castellan

- Zofia Odrowąż,

1540-1580

- Jan Zamoyski, 1542-1605, hetman and chancellor

- Jan Opaliński, 1546-1598

- Mikołaj VII Radziwiłł, 1546-1589, chambelain

- Krzysztof Mikołaj "the Lightning" Radziwiłł, 1547-1603, hetman

- Stanisław Żółkiewski, 1547-1620, hetman, catellan, chancellor

- Mikołaj Krzysztof "the Orphan" Radziwiłł, 1549-1616, voivode

- Marek Sobieski, 1549-1605, voivode

- Stanisław Kostka, 1550-1568, saint

- Jan Tarnowski, 1550-1605, archbishop

- Stanisław

Stadnicki, 1551-1610

- Jan Kiszka, 1552-1592

- Andrzej Leszczyński, 1553-1606, starost of Nakło, voivode of Brześć

Kujawski

- Mikołaj Zebrzydowski, 1553-1620, voivode

- Janusz Ostrogski, 1554-1620, castellan, voivode

- Adam Sędziwój Czarnkowski, 1555-1628, voivode

- Jan Zbigniew Ossoliński, 1555-1628, Kings secretary

- Aleksander Koniecpolski, 1555-1609, voivode

- Jerzy Radziwiłł, 1556-1600, bishop

- Lew

Sapieha, 1557-1633, hetman, voivode

- Stanisław

Krasiński, 1558-1617, voivode

- Jan Karol Chodkiewicz,

1560-1621, hetman

- Katarzyna Ostrogska, 1560-157

- Krystyna Radziwiłł, 1560-1580

- Mikołaj Spytek Ligęza, 1562-1637, castellan

- Zygmunt Tarło, 1562-1628, castellan

- Marcin Kazanowski, 1563/1566-1636, hetman, chancellor, voivode

- Zygmunt Kazanowski, 1563-1634, starost, courth marshall and chamberlain

- Konstanty Wiśniowiecki, 1564-1641, voivode

- Barbara Tarnowska, 1566-1610

- Adam

Wiśniowiecki, 1566-1622

- Jan Szczęsny Herburt,

1567-1616, starost

- Jan Piotr Sapieha, 1569-1611, starosta

uświacki, pułkownik królewski

- Janusz

Skumin Tyszkiewicz, 1570-1642, voivode, writer

- Aleksander

Ostrogski, 1571-1603, voivode

- Daniel Naborowski, 1573-1640,

poet

- Jerzy Zbaraski, 1573-1631, castellan

- Anna Kostka, 1575-1635

- Katarzyna

Kostka, 1575-1648

- Adam Hieronim Sieniawski, 1576-1616,

starost, podczaszy

- Grzegorz IV Radziwiłł,

1578-1613, castellan

- Rafał Leszczyński,

1579-1636, voivode

- Janusz Radziwiłł, 1579-1620,

castellan

- Stanisław "Rewera" Potocki,

1579-1667, hetman

- Aleksander Józef Lisowski,

1580-1616, mercenary commander

- Szymon Okolski, 1580-1653,

historian, priest

- Jakub Sobieski, 1580/88-1646, voivode

- Krzysztof Zbaraski, 1580-1628, koniuszy, ambassador

- Hieronim Morsztyn, 1581-1623, poet

- Jan Opaliński, 1581-1637, voivode of Poznań

- Łukasz Opaliński, 1581-1654, voivode

- Jan Tęczyński, 1581-1637, voivode of Kraków

- Jakub Zadzik, 1582-1642, bishop and chancellor

- Stanisław Lubomirski, 1583-1649

- Zofia

Czeska, 1584-1650, nun

- Piotr Gembicki, 1585-1657,

chancellor

- Zofia Lubomirska, 1585-1612

- Krzysztof II Radziwiłł, 1585-1640, hetman

- Szymon Starowolski, 1585-1650, priest, writer

- Samuel Korecki, 1586-1622

- Piotr

Opaliński, 1586-1624

- Kasper Doenhoff, 1587-1645,

voivode

- Krzysztof Ossoliński, 1587-1645, voivode

- Stefan Pac, 1587-1640, chancellor

- Mikołaj Firlej, 1588-1635, wojewoda sandomierski

- Marina Mniszech, 1588-1614

- Samuel Łaszcz,

1588-1649, starosta, (warchoł means brawler, barrator)

- Albrycht Władysław Radziwiłł, 1589-1636, castellan

- Jan Stanisław Sapieha, 1589-1635, Chancellor of Lithuania from 1621-1635, childless

- Stanisław Koniecpolski, 1590/1594-1646, hetman

- Jakub Sobieski, 1590-1646, voivode

- Janusz Tyszkiewicz Łohojski, 1590-1649, voivode

- Andrzej Bobola, 1591-1657, jesuit, martyr, saint

- Zygmunt Karol Radziwiłł, 1591-1642, voivode

- Zdzisław Jan Zamoyski, 1591-1670, castellan

- Krzysztof

Arciszewski, 1592-1656, General of Artillery

- Mikołaj

Ostroróg, 1593-1651, sejm marshal

- Jan Karol

Tarło, 1593-1645, castellan

- Aleksander Ludwik

Radziwiłł, 1594-1654, voivode

- Tomasz Zamoyski,

1594-1638, voivode, chancellor,

- Bogdan Chmielnicki,

1595-1657, hetman

- Jerzy Ossoliński, 1595-1650,

voivode and chancellor

- Mikołaj Potocki, 1595-1651,

castellan, hetman

- Albrycht Stanisław Radziwiłł,

1595-1656, chancellor

- Stanisław Lanckoroński,

1597-1657, voivode

- Janusz Wiśniowiecki, 1598-1636,

starost, koniuszy

- Adam Kazanowski, 1599-1649

- Stefan Czarniecki, 1599-1665, hetman

- Jan Zamoyski, 16th century-?

- Barbara

Lubomirska, 16th century-?

- Paweł Tarło,

16th century-1565, bishop

- Jan Tarło, 16th century-1571

- Samuel Zborowski, 16th century-1584

- Stanisław Lubomirski, 16th century-1585

- Mikołaj Firlej, 16th century-1588

- Krzysztof

Kosiński, 16th century-1593

- Jan Tęczyński,

16th century-1583, castellan, podkomorzy

- Stanisław

Tarło 16th century-1600, starost

- Mikołaj

Firlej,, 16th century-1601, wojewoda krakowski

- Fiodor

Trubecki, 16th century-1608, prince

- Joachim Lubomirski,

16th century-1610, starost

- Katarzyna Lubomirska, 16th

century-1611

- Jerzy Mniszech. 16th century-1613, voivode

- Michał Wiśniowiecki, 16th century-1616, castellan

- Jan Zamoyski, 16th century-1619, castellan

- Wigund-Jeronym Trubecki, 16th century-1634, prince

- Henryk Firlej, 16th century-1626, bishop

- Krzysztof Wiesiołowski, 16th century-1637, marshal

- Anna Branicka, 16th century-1639

- Aleksander

Korwin Gosiewski, 16th century-1639

- Zofia Krasińska,

16th century-1642

- Katarzyna Potocka, 16th century-1642

- Piotr Trubecki, 16th century-1644, podkomorzy, chamberlain

- Krystyna Lubomirska, 16th century-1645

- Stanisław Kazanowski, 16th century-1648

- Konstancja Ligęza, 16th century-1648

- Krzysztof

Chodkiewicz, 16th century-1652, castellan, voivode

- Jan

Kazimierz Umiastowski, 16th century - 1659, sejm marshal

- Samuel

Twardowski, 16th century (1590s) - 1661, writer

The 17th Century Polish Nobility - Anna Eufrozyna Chodkiewicz, 1600-1631

- Adam

Kisiel, 1600-1653, voivode

- Janusz Kiszka, 1600-1653

- Kazimierz Siemienowicz, 1600-1651, general, scientist

- Katarzyna Ostrogska, 1602-1642

- Prokop Sieniawski, 1602-1626, chorąży

- Marcin

Kalinowski, ca. 1605-1652, field crown hetman, voivode

- Dominik

Aleksander Kazanowski, 1605-1648, voivode

- Andrzej

Leszczyński, 1606-1651, voivode

- Jan Kazimierz

Krasiński, 1607-1669, voivode

- Andrzej Trebicki,

1607-1679, bishop

- Andrzej Leszczyński, 1608-1658,

chancellor and primate

- Jan Paweł Sapieha, 1609-1665,

voivode

- Krzysztof Opaliński, 1611-1655, voivode

- Bogusław Leszczyński, 1612-1659, starost

- Łukasz Opaliński, 1612-1666

- Hieronim Radziejowski, 1612-1667, chancellor

- Janusz Radziwiłł 1612-1655, hetman, voivode

- Jeremi Wiśniowiecki, 1612-1651, voivode

- Kazimierz

Franciszek Czarnkowski, 1613-1656

- Mikołaj Krzysztof

Sapieha, 1613-1639, voivode

- Bogusław Leszczyński,

1614-1659

- Aleksander Michał Lubomirski, 1614-1677

- Jan Kazimierz Chodkiewicz, 1616-1660, castellan of Vilna

- Jerzy Sebastian Lubomirski, 1616-1667

- Władysław Dominik Zasławski, 1616-1656, voivode

- Anna Krystyna Lubomirska, 1618-1667

- Konstancja

Lubomirska, 1618-1646

- Andrzej Potocki, 1618-1663.

voivode

- Aleksander Koniecpolski Junior, 1620-1659,

voivode, starost, chorazy

- Konstanty Jacek Lubomirski,

1620-1663, starost

- Bogusław Radziwiłł,

1620-1669

- Andrzej Maksymilian Fredro, 1620-1679, writer

- Wincenty Korwin Gosiewski, 1620-1662

- Krzysztof Grzymułtowski, 1620-1687, voivode

- Krzysztof Zygmunt Pac, 1621-1684, chancellor

- Wacław

Potocki, 1621-1696, poet, writer

- Adam Hieronim Sieniawski,

1623-1650, starost

- Gryzelda Konstancja Zamoyska, 1623-1672,

princess

- Wincenty Gosiewski, 1625-1662

- Michał Kazimierz Radziwiłł, 1625-1680, hetman, chancellor

- Joanna Barbara Zamoyska, 1626-1653

- Jan "Sobiepan" Zamoyski, 1627-1662, voivode

- Marek Sobieski, 1628-1652, starost

- Jan

III Sobieski, 1629-1696, king

- Stefan Bidziński,

1630-1704, voivode

- Jan Chryzostom Pieniążek,

1630-1712, voivode

- Feliks Kazimierz Potocki, 1630-1702,

hetman

- Jan Wielopolski, 1630-1688, chancellor

- Dymitr Jerzy Wiśniowiecki, 1631-1682, hetman, voivode

- Stanisław Jan Jabłonowski, 1634-1702, hetman

- Jan Chryzostom Pasek, 1636-1701, soldier and writer,

- Jan Kazimierz Sapieha the Younger, ca. 1637/1642-1720, since 1700 held the title of a Duke.

Since 1681 FieldHetman of Lithuania, the following year he also became the voivod of Vilna. In 1682 promoted

to Grand Hetman of Lithuania.

- Marcin Zamoyski, 1637-1689,

voivode

- Józef Karol Lubomirski, 1638-1702,

marshal, koniuszy, starost

- Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki,

1640-1694

- Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki, 1640-1673,

king

- Stanisław Herakliusz Lubomirski, 1642-1702,

marshall, starost

- Jan Karol Opaliński, 1642-1695,

castellan of Poznań, starost

- Stanisław Mateusz

Rzewuski, 1642-1728, voivode

- Marianna Kazanowska,

1643-1687

- Dominik Radziwiłł, 1643-1697,

chancellor

- Katarzyna Sobieska, 1643-1694

- Cecylia Maria Radziwiłł, 1643-1682

- Dominik Mikołaj Radziwiłł, 1643-1697, chancellor

- Teresa Chodkiewicz, 1645-1672

- Mikołaj

Hieronim Sieniawski, 1645-1683, hetman

- Hieronim Augustyn

Lubomirski, 1647-1706, hetman

- Rafał Leszczyński,

1650-1703

- Stanisław Antoni Szczuka, 1652-1710,

chancellor

- Jerzy Dominik Lubomirski, 1654-1727, voivode

- Teresa Lubomirska, 1658-1712

- Anna Jabłonowska, 1660-1727

- Andrzej

Taczanowski, c. 1660-18th century, knight commander 1683 Battle of Vienna

- Teodor Andrzej Potocki, 1664-1738, primate

- Adam Mikołaj Sieniawski, 1666-1726, hetman

- Jakub

Ludwik Sobieski, 1667-1737, crown-prince

- Elżbieta

Lubomirska, 1669-1729

- Karol Stanisław Radziwiłł,

1669-1719, koniuszy, chancellor

- Stanisław Ernest

Denhoff, 1673-1728, hetman

- Stanisław Chomętowski,

1673-1728, hetman

- Florian Pacanowski, 1673-1725, ambassador

- Józef Potocki, 1673-1752, hetman

- Kazimierz Czartoryski, 1674-1741

- Józef

Lubomirski, 1676-1732, voivode

- Franciszek Maksymilian

Ossoliński, 1676-1756, treasurer, zupnik, starost

- Stanisław

Poniatowski, 1676-1762

- Teresa Kunegunda Sobieska,

1676-1730

- Stanisław Leszczyński, 1677-1766,

king

- Aleksander Benedykt Sobieski, 1677-1714, prince

- Tomasz Józef Zamoyski, 1678-1725, starost

- Michał Zdzisław Zamoyski, 1679-1735, voivode

- Jan Fryderyk Sapieha, 1680-1751, Grand Recorder of Lithuania between 1706 and

- 1709, since 1716 the castellan of Troki and after 1735 the Grand Chancellor

of Lithuania

- Konstanty Władysław Sobieski,

1680-1726, prince

- Michał Serwacy Wiśniowiecki,

1680-1744, chancellor, hetman

- Franciszek Bieliński,

1683-1766, marshal, voivode

- Teodor Lubomirski, 1683-1745

- Jan Tarło, 1684-1750, voivode

- Jerzy Ignacy Lubomirski, 1687-1753

- Jan

Klemens Branicki, 1689-1771, magnate, hetman, castellan

- Stefan

Garczyński, voivode of Poznań, writer

- Aleksander

Dominik Lubomirski, 1693-1720

- Marianna Lubomirska,

1693-1729

- Katarzyna Barbara Radziwiłł, 1693-1730

- Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł, 1695-1715, podstoli, starost

- Andrzej Stanisław Załuski, 1695-1758, bishop

- Michał Fryderyk Czartoryski, 1696-1775, castellan, chancellor

- August Aleksander Czartoryski, 1697-1782

- Maria Zofia Sieniawska, 1698-1771, countess

- Jerzy Detloff Fleming, 1699-1771

- Zuzanna

Korwin Gosiewska, 17th century-1660

- Krystyna Lubomirska,

17th century-1669

- Wiktoria Elżbieta Potocka,

17th century-1760

- Aleksander Michał Lubomirski,

17th century-1673

- Stanisław Koniecpolski, 17th

century-1682, voivode

- Jan Wielopolski, 17th century-1688,

castellan, voivode

- Andrzej Potocki, 17th century-1692

- Franciszek Sebastian Lubomirski, 17th century-1699

- Anna Krystyna Lubomirska, 17th century-1701

- Teresa Korwin Gosiewska, 17th century-1708

- Jan Dobrogost Krasiński, 17th century-1717

- Jan

Aleksander Koniecpolski, 17th century-1719, voivode, starosta

- Franciszek Lubomirski, 17th century-1721

- Józef

Potocki, 17th century-1723, starost

- Jan Kazimierz

Sapieha the Elder 17th century-1730, Grand Hetman of Lithuania

- Jan Szembek, 17th century-1731, chancellor

- Franciszek

Wielopolski, 17th century--1732, voivode

- Aleksander

Jan Jabłonowski, 17th century-1733

- Jerzy Aleksander

Lubomirski, 17th century-1735

- Anna Lubomirska, 17th

century-1736

- Jan Lubomirski, 17th century-1736

- Antoni Benedykt Lubomirski, 17th century-1761

- Krystyna Branicka, 17th century-1767

The 18th Century Polish Nobility - Konstancja Czartoryska, 1700-1759

- Michał

Józef Massalski, c. 1700-1768, hetman

- Franciszek

Salezy Potocki, 1700-1772, voivode

- Count Karol Antoni

Usakowski 1750-1825, Count,voivode

- Jan Wielopolski,

1700-1773, voivode

- Michał Kazimierz "Rybeńko"

Radziwiłł, 1702-176, hetman, castellan,

- Maria

Klementyna Sobieska, 1702-1735, crown princess

- Józef

Andrzej Załuski, 1702-1774, bishop

- Maria Leszczyńska,

1703-1768, princess

- Stanisław Lubomirski, 1704-1793,

voivode

- Michał Grocholski, 1705-1765, cześnik

- Wacław Rzewuski, 1705-1779, hetman

- Tomasz Antoni Zamoyski, 1707-1752, voivode

- Marianna Jabłonowska, 1708-1765

- Franciszek

Ferdynant Lubomirski, 1710-1747

- Józef Aleksander

Jabłonowski, 1711-1777, voivode

- Mikołaj

Bazyli Potocki, 1712-1782, starost

- Andrzej Mokronowski,

1713-1784, voivode

- Adam Tarło, 1713-1744, voivode

- Hieronim Florian Radziwiłł, 1715-1760, podczaszy, starost

- Kajetan Sołtyk, 1715-1788, bishop

- Andrzej Zamoyski, 1716-1792, voivode, chancellor

- Jan Jakub Zamoyski, 1716-1790, voivode

- Antoni

Lubomirski, 1718-1782, voivode

- Kazimierz Poniatowski,

1721-1800, podkomorzy

- Rafael Taczanowski, 1721-18th

century, head of the Jesuit Order in Poland

- Jacek

Jezierski, 1722-1805

- Stanisław Lubomirski, 1722-1782,

prince

- Celestyn Czaplic, 1723-1803, podczaszy, podkomorzy,

koniuszy

- Kazimierz Krasiński, 1725-1802

- Piotr Ożarowski, 1725-1794, hetman

- Ignacy Jakub Massalski, 1726-1794, bishop

- Antonina Czartoryska, 1728-1746, princess

- Anna

Luiza Mycielska, 1729-1771

- Franciszek Ksawery Branicki,

1730-1819, magnate, hetman

- Franciszek Grocholski,

1730-1792

- Maria Karolina Lubomirska, 1730-1795

- Izabella Poniatowska, 1730-1801

- Aniela Miączyńska, 1731-?

- Antoni

Barnaba Jabłonowski, 1732-1799

- Tomasz Sołtyk,

1732-1808, castellan

- Stanisław August Poniatowski,

1732-1798, king

- Adam Naruszewicz, 1733-1798, writer,

bishop

- Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski, 1734-1823, prince

- Stanisław Potocki, 1734-1802, starost, krajczy

- Karol Stanisław "Panie Kochanku" Radziwiłł, 1734-1790, prince,

voivode

- Ignacy Krasicki, 1735-1801, bishop, writer

- Tomasz Adam Ostrowski, 1735-1817, castellan

- Andrzej Poniatowski, 1735-1773

- Elżbieta

Czartoryska, 1736-1816

- Stanisław Małachowski,

1736-1809

- Michał Jerzy Poniatowski, 1736-1794,

archbishop

- Józef Mikołaj Radziwiłł,

1736-1813, voivode

- Elżbieta Czartoryska, 1736-1816,

princess

- Jacek Małachowski, 1737-1821

- Tadeusz Franciszek Ogiński, 1737-1783, voivode

- Stanisław Ferdynand Rzewuski, 1737-1786

- Józef Klemens Czartoryski, 1740-1810

- Szymon Marcin Kossakowski, 1741-1794

- Michał

Jerzy Mniszech, 1742-1806, marshal

- Tadeusz Rejtan,

1742-1780

- Seweryn Rzewuski, 1743-1811, hetman

- Michał Hieronim Radziwiłł, 1744-1831

- Maria Ludwika Rzewuska, 1744-1816

- Kazimierz Pułaski, 1745-1779

- Ignacy

Wyssogota Zakrzewski, 1745-1802

- Izabela Fleming, 1746-1835,

countess

- Tadeusz Kościuszko, 1746-1817, general

- Klemens Zamoyski, 1747-1767, starost

- Józef Maksymilian Ossoliński, 1748-1829

- Maciej Radziwiłł, 1749-1800, podkomorzy

- Hugo Kołłątaj, 1750-1812, chancellor

- Roman Ignacy Potocki, 1750-1809

- Józefina

Amalia Mniszech, 1752-1798

- Józef Zajączek,

1752-1826, general

- Stanisław Szczęsny Potocki,

1753-1805, voivode

- Stanisław Sołtyk, 1753-1831

- Ignacy Działyński, 1754-1797, military officer

- Stanisław Poniatowski, 1754-1833

- Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, 1755-1818, Polish general

- Gertruda Komorowska, 1755-1771

- Elżbieta

Lubomirska, 1755-1783, princess

- Stanisław Kostka

Zamoyski, 1755-1856, voivode

- Jan Krasiński, 1756-1790

- Stanisław Kostka Potocki, 1757-1821

- Kazimierz Nestor Sapieha, 1757-1798, artillery general

- Kazimierz Jordan-Rozwadowski, 1757-1836, Polish Patriot

- Józef Kajetan Ossoliński, 1758-1834, castellan

- Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, 1758-1841, writer

- Władysław Franciszek Jabłonowski, 1769-1802

- Hieronim Wincenty Radziwiłł, 1759-1786, podkomorzy

- Dominik Dziewanowski, 1759-1827, Virtuti Militari

- Dorota Barbara Jabłonowska, 1760-1844

- Aleksandra Lubomirska, 1760-1836

- Konstancja

Małgorzata Lubomirska, 1761-1840

- Stanisław

Mokronowski, 1761-1821, general

- Antoni Protazy Potocki,

1761-1801

- Jan Potocki, 1761-1815

- Karol Kniaziewicz, 1762-1842

- Józef Antoni Poniatowski, 1763-1813, prince

- Julia Lubomirska, 1764-1794

- Michał Kleofas

Ogiński, 1765-1833

- Jan Henryk Wołodkowicz,

1765-1825

- Eustachy Erazm Sanguszko, 1768-1844

- Maksymilian Taczanowski, 177?-1852, national revolutionary

- Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, 1770-1861, prince

- Jan Krukowiecki, 1772-1850

- Konstanty

Adam Czartoryski, 1773-1860

- Rajmund Rembliński,

1774-1820

- Antoni Radziwiłł, 1775-1833

- Ludwik Pac, 1778-1835

- Aleksander

Stanisław Potocki, 1778-1845, castellan

- Michał

Gedeon Radziwiłł, 1778-1850

- Klementyna Czartoryska,

1780-1852

- Zofia Czartoryska, 1780-1837

- Antoni Potocki, 1780-1850, castellan

- Jan Kozietulski, 1781-1821

- Wincenty

Krasiński, 1782-1858

- Antoni Jan Ostrowski, 1782-1845,

castellan, general

- Władysław Grzegorz Branicki,

1783-1843

- Alfred Wojciech Potocki, 1785-1862, ochmistrz

of Galicia

- Edward Raczyński, 1786-1845

- Dominik Hieronim Radziwiłł, 1786-1813

- Józefina Maria Czartoryska, 1787-1862

- Artur Potocki, 1787-1832

- Dezydery Chłapowski,

1788-1879, general

- Marie, Countess Walewski, 1789-1817

- Zofia Branicka, 1790-1879

- Władysław Ostrowski, 1790-1869

- Roman

Sołtyk, 1790-1843

- Sir Paweł Edmund

Strzelecki, 1797-1873, explorer

- Anna Zofia Sapieha,

1799-1864

- Konstanty Zamoyski, 1799-1866

- Stanisław Potocki, 18th-century-1760, voivode

- Anna Lubomirska, 18th-century-1763

- Józef Sawa-Caliński, 18th-century-1771

- Aleksander August Zamoyski, 18th-century-1800

- Ludwika Lubomirska, 18th-century-1829

- Józef

Makary Potocki, 18th-century-1829

- Zenon Kazimierz

Wysłouch, 1727-1805,

- chamberlain

of the Brzeskie Voivodeship

The 19th Century Polish Nobility - Roman

Sanguszko, 1800-1881

- Andrzej Artur Zamoyski, 1800-1874

- Ewelina Hańska, 1801-1882

- Władysław Hieronim Sanguszko, 1803-1870

- Aleksander Wielopolski, 1803-1877

- Leon Sapieha,

1803-1878

- Władysław Stanisław Zamoyski,

1803-1868, general, revolutionary

- Przemysław

Potocki, 1805-1847

- Emilia Plater, 1806-1831, revolutionary

- Franciszka Ksawera Brzozowska, 1807-1872

- Delfina Potocka, 1807-1877

- Szymon

Konarski, 1808-1839, revolutionary

- Alexandre Joseph

Count Colonna-Walewski, 1810-1868

- Zdzisław Zamoyski,

1810-1855

- Antoni Patek, 1811-1877

- Agenor Gołuchowski, 1812-1875

- Kazimierz Gzowski, 1813-1898, engineer

- Tomasz

Chołodecki, 1813-1880, political activist

- Alfons

Anton Felix Count Taczanowski, 1815-1867, member of Prussian House of Lords

- Celestyn Chołodecki 1816-1867

- Alfred Józef Potocki, 1817-1889, sejm marshal, prime minister of Austria-Hungary

- Władysław Taczanowski, 1819-1890, zoologist

- Eliza Branicka, 1820-1876, wife of famous poet Zygmunt Krasiński

- Edmund Taczanowski, 1822-1879, general, revolutionary

- Witold Czartoryski, 1824-1865

- Katarzyna Branicka, 1825-1907

- Włodzimierz

Dzieduszycki, 1825-1899

- Wladislaw Taczanowski, 1825-1893

- Jerzy Konstanty Czartoryski, 1828-1912

- Władysław Czartoryski, 1828-1894

- Władysław Umiastowski,1831-1905, marshal of szlachta, count

- Izabella Elżbieta Czartoryska, 1832-1899

- Tomasz Franciszek Zamoyski, 1832-1889

- Maria

Grocholska, 1833-1928

- Mikołaj Światopełk-Mirski,

1833-1898

- Raphael Kalinowski, 1835-1907

- Stanisław Antoni Potocki, 1837-1884

- Stanisław Tarnowski, 1837-1917

- Stefan

Zamoyski, 1837-1899

- Konstanty Kalinowski, 1838-1864,

- Alfonsyna Miączyńska, 1838-1919

- Nester Trubecki, c.1840-1907, prince

- Eustachy

Stanisław Sanguszko, 1842-1903

- Władysław

Krasiński, 1844-1873

- Kasimir Felix Graf Badeni,

1846-1909

- Bolesław Prus, 1847-1912

- Edward Aleksander Raczyński, 1847-1926

- Agenor Maria Gołuchowski, 1849-1921

- Maria Beatrix Krasińska, 1850-1884

- Artur

Władysław Potocki, 1850-1890

- Roman Potocki,

1851-1889, count

- Józef Białynia Chołodecki 1852-1934

- Władysław Zamoyski, 1854-1924

- August Czartoryski, 1858-1893

- Witold

Leon Czartoryski, 1864-1945

- Zdzisław Lubomirski,

1865-1943

- Tadeusz Jordan-Rozwadowski, 1866-1928, Polish

General, chief of staff

- of the Polish Army,

major contributor to victory at the Battle of Warsaw

- Jadwiga

Dzieduszycka, 1867-1941

- Jan Nepomucen Potocki, 1867-1943

- Adam Stefan Sapieha, 1867-1951

- Rodryg Dunin, 1870-1928

- Waclaw Iwaszkiewicz Polish

general in the Polish-Soviet war (1919-1920)

- Maurycy

Klemens Zamoyski, 1871-1939

- Adam Ludwik Czartoryski 1872-1937

- Wacław Sobieski, 1872-1935

- Władysław Zdzisław Zamoyski, 1873-1944

- Paweł Trubecki, 1879-1941, prince

- Maria

Ludwika Krasińska, 1883-1958

- Alfred Niezychowski,

1888-1964

- Samuel Tyszkiewicz, 1889-1954

- Stanisław Bohdan Grabiński, 1891-1930

- Edward Raczyński, 1891-1993, president

- Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, 1895-1966, Polish general

- Jan Franciszek Czartoryski, 1897-1944

- Roman

Jacek Czartoryski, 1898-1958

- Krzysztof Mikołaj

Radziwiłł, 1898-1986

The 20th Century Polish Nobility

Nobility privileges were abolished under the Second Polish Republic (1918-1939).

Nobility obligations are not addressed. This would leave the legal status of nobility as consisting of obligations only (as

they demonstrated in WW2) had the article been not later revoked anyway. - Stefan Adam Zamoyski, 1904-1976

- Elżbieta

Czartoryska, 1905-1989

- Adam Michał Czartoryski,

1906-1998

- Augustyn Józef Czartoryski, 1907-1944

- Antoni Dunin, 1907-1939

- Piotr

Michał Czartoryski, 1909-1993

- Kurnatowski of

Lodzia. Zygmunt Obtained the hereditary

- papal

title of Count from Pope Leo XIII in 1902.

- Jan Zamoyski

(1912-2002), 1912-2002

- Stanisław Albrecht Radziwiłł,

1914-1976

- Włodzimierz Wałoc Trubecki, 1915-1997,

prince

- Professor Pawel Czartoryski, 1924-1999

- Władysław Krzysztof Grabiński, 1925-1944

- Jan Trubecki, 1938, prince

- Adam Karol Czartoryski, 1940

- Adam Zamoyski,

1949

- Hubert Taczanowski, 1960

- Princess Tamara Laura Czartoryska-Borbon, 1978

- Aleksander Kochankrólewski, 1989

- Seweryn Wysłouch, 1900-1968

The Index of Polish Princely Houses Czartoryski h. Pogon Litewska. Dynastic Princely title confirmed in Poland and Lithuania

in 1569, in Hungary in 1442 and 1808, in Austria in 1785 and 1863, in the Kingdom of Poland in 1815,

1819 and 1824. Qualification of Serene Highness accorded in Austria, July 20 1905. Czetwertynski h. Pogon Ruska. The Czetwertynski

family appears in the 1824 list of persons authorised to bear the title of Prince in the Kingdom of Poland. The title was recognised in Rusia

in 1843, 1858, 1860, 1875 and 1886. Drucki-Lubecki h. Druck. The right to the title of Prince was recognised

in Prussia

on December 21 1798, in Russia on January 24 1851 and May 12 1852. Giedroyc

h. Poraj. Princely title received Russian confirmation in 1865, 1866, 1875, 1876, 1878 and 1880. Gulgowski

h. Doliwa Princely and Ducal House of Gulgowski-Doliwa

bear the titles of Prince, Duke and Count of the

Holy Roman Empire

of the German Nation and of the Kingdom of Poland. Titles recognized by King Frederick The Great Patent, dated 13 September

1772 . Jablonowski

h. Prus III. Hereditary title of Prince of the Holy Roman Empire granted by Emperor Charles VII to various members of the family

in 1743 and 1744. Title was recognised in Poland in 1775, in Austria in 1777, 1820 and 1827 and in Russia in 1844. In 1824

the Jablonowskis appeared in the list of families authorised to bear the title of Prince in the Kingdom of Poland. On July 20

1905

the Jablonowskis received confirmation of their right to the qualification of Serene Highness

(originally granted in 1704). Lubomirski h. Szreniawa bez Krzyza. Title of Count of the Holy Roman Empire awarded to Sebastian Lubomirski on July 14 1595. His son

Stanislaw was awarded the hereditary title of Prince of the Holy Roman Empire by Emperor Ferdinand III on March 8

1647. Title was confirmed in Austria on June 6 1786, in Russia on May 21 1863 and March 8 1888. In 1824 the Lubomirskis

appeared in the list of families authorised to bear the title of Prince in the Kingdom of Poland. On July 20 1905 the Lubomirskis were

awarded the qualification of Serene Highness. Massalski h. Massalski. In 1775 the Massalskis were granted the hereditary

title of

Prince by the Polish Sejm (parliament). This branch became extinct on May 9 1794. Various members of the non-titled branch

obtained confirmation of their right to the title of Prince in Russia on September 7 1862, April 7 1864, June 24 1868, January 22 1885 and

March 21 1889 Oginski h. Oginiec. The right of the family to bear the title of Prince was recognised in Austria by Emperor Joseph

II on 17 March 1783, in the Kingdom of Poland by the Senate on 25 March 1821 and in Russia by Czar Alexander II on 3 April 1868. In 1824

the Oginskis appeared in the list of families authorised to bear the title of Prince in the Kingdom of Poland. Ossolinski h. Topor. Various titular grants: Jerzy Ossolinski obtained

the hereditary

title of Prince from Pope Urban VIII on 23 December 1633, the non-hereditary title of Prince of the Holy Roman

Empire from Emperor Ferdinand II on 20 January 1634. The hereditary title became extinct upon the death of Jerzy's only son.

Franciszek-Maximilian Ossolinski obtained the title of Duke from King Louis XV of France on 1 January 1736. The title

became extinct in 1790. Michal Ossolinski obtained the right to the hereditary title of Count of Austria from Emperor Joseph

II on 7 July and 9 August 1785. Jozef-Kajetan Ossolinski obtained the hereditary title of Count from Kaiser Frederick-Wilhelm, of Prussia on 15 November

1805 (L.P. 1 October 1806). Wiktor-Maximilian-Josef Ossolinski obtained the hereditary title of Count in Russia on 7 January 1848.

In 1824

the Ossolinskis appeared in the list of families authorised to bear the title of Count of the Kingdom of Poland. Poniatowski

h. Ciolek. In 1764 the brothers of King Stanislaw-Augustus Poniatowski (Kazimierz, Andrzej and Michal) were awarded the hereditary title of Prince of Poland by the Polish

Sejm (parliament). On 10 December 1765 Emperor Joseph II also awarded Andrzej the hereditary title

of Prince in Austria (succession by primogeniture). Karol

and Stanislaw-Michal-Ksawery Poniatowski obtained the

hereditary title of Prince from Austrian Emperor Franz-Josef on 19 November 1850. Poninski h. Lodzia. Various grants: Princely title awarded to Adam

and Calixte Poninski

by the Sejm on 19 April 1773. The descendants of Adam were granted the hereditary title of Prince in Austria on

30 December 1837 and 22 May 1841. Alexsander-Franciszek Poninski was awarded the qualification of Serene Highness by Emperor Franz-Josef on

20 July 1905. Ignacy-Augustus Poninski obtained the Prussian hereditary title of Count on 4 August 1782. This title was later confirmed in Austria on 8 March 1842 and 8 March 1862. Wladyslaw-Augustus obtained the hereditary title of Count in Italy on 24 February 1880. The title became extinct in the following generation. Stanislaw obtained the Prussian hereditary title of Count on 10 Septemer 1840 (sucession by primogeniture with added stipulation that the mother of each heir be noble in her own right). Antoni Poninski obtained the Bavarian title of Count on 18 August 1841. Adolphus Poninski obtained the Papal title of Count from Pope Pius X in 1908. On 25 March 1888 Bronislaw Poninski obtained the non-hereditary title of Count from King Umberto I of Italy. Puzyna

h. Oginiec. The right to bear the title of Prince was recognised by the Kingdom of Poland in a senate decision in 1823, in Russia

on 17 May and 6 June 1910, 3 July and

24 September 1915 and 21 January 1916. In 1824 the Puzynas were

listed among those families authorised to bear the title of Prince in the Kingdom of Poland. Radziwill h. Traby. The Radziwills received confirmation of their right to the

title of Prince of the Holy Roman Empire in 1547; in Poland in 1564/1569; in Austria in 1784 and 1882; in the Kingdom of Poland

in 1824 and in Russia in 1845, 1867 and 1899. The qualification of Serene Highness was accorded in Prussia in 1859 and 1861

and in Austria in 1905. Sanguszko h. Pogon Litweska. The Sanguszko dynasty received confirmation

of the

title of Prince in Poland in 1569; in Austria in 1785, 1833 and 1835 and in Russia in 1858 and 1906. In 1905 the Princes

Sanguszko received the qualification of Serene Highness from Austrian Emperor Franz-Josef. Sapieha h. Lis. Michal-Franciszek

obtained the hereditary title of Prince of the Holy Roman Empire from Emperor Leopold I on 14th September 1700. The title became extinct upon his death

without issue on 19th November 1700. In 1768 all the members of the Sapieha family obtained recognition of the princely title

from the Polish sejm (parliament). In 1824 the Sapieha family appeared in the list of persons authorised to bear the title of Prince

of the Kingdom Poland. The title was also recognised by the Austrians in 1836 and 1840, and in Russia in 1874 and 1901. In 1905 they obtained

the qualification of Serene Highness in Austria. Sulkowski h. Sulima. Title of Count of the Holy Roman Empire obtained

in 1733.

Title of Prince obtained in Bohemia in 1752 (succession by primogenitue). Twelve years later the right of succession was

extended to all descendants. In 1774 the title of Prince of the Holy Roman Empire was recognised in Poland. The Sulkowskis received the Prussian

qualification of Serene Highness in 1819 and the Austrian qualification of Serene Highness in 1905. Woroniecki h. Korybut. In 1824 the Woronieckis were listed amongst those persons authorised to bear the title of Prince of the Kingdom of Poland. The princely title was recognised

in Russia on 28th June 1844 and 5th July 1852. Zajaczek h. Swinka. On 17th April 1818 Joseph Zajaczek (29th March 1752-13th February

1845) obtained the hereditary title of Prince of the Kingdom of Poland from Czar Aleksander I. The title became extinct

upon his death without issue.

|