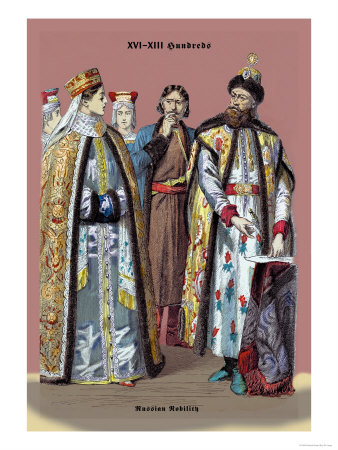

Nobility of the World

Volume VIII - Russia

The Russian nobility (Russian: Дворянство

Dvoryanstvo) arose in the 14th century and essentially governed Russia until the October Revolution of 1917. The Russian word

for nobility, Dvoryanstvo (дворянство), derives from the Russian

word dvor (двор), meaning the Court of a prince or duke (kniaz) and later, of the tsar. A noble was

called dvoryanin (pl. dvoryane). As in other countries, nobility was a status, a social category, but not a title.

The History of the Nobility

of Russia

The nobility

arose in the 12th and 13th centuries as the lowest part of the feudal military class, which composed the court of a prince

or an important boyar. From the 14th century land ownership by nobles increased, and by the 17th century it composed the bulk

of feudal lords and constituted the majority of landowners. They made Landed army (Russian: поместное

войско) - the basic military force of Muscovy. Peter the Great finalized the status of

the nobility, while abolishing the boyar title.

From 1782, a kind of uniform was introduced for civilian nobles called uniform of civilian service or simply

civilian uniform. The uniform prescribed colors that depended on the territory. The uniform was required at the places of

service, at the Court, and at other important public places. The privileges of the nobility were fixed and were legally codified

in 1785 in the Charter to the Gentry. The Charter introduced an organization of the nobility: every province (guberniya) and

district (uyezd) had an Assembly of Nobility. The chair of an Assembly was called Province/District Marshal of Nobility.

By 1805, the various ranks of the

nobility had become confused, as is apparent in War and Peace. Here, we see counts who are wealthier and more important than

princes. We see many noble families whose wealth has been dissipated, partly through lack of primogeniture and partly through

extravagance and poor estate management. We see young noblemen serving in the Army, but we see none who acquire new landed

estates that way. (This refers to the era of the Napoleonic Wars. Tolstoy reported some improvement afterwards: some nobles

paid more attention to estate management, and some, like Andrey Bolkonsky, freed their serfs even before the tsar did so in

1861.

After the peasant reform

of 1861 the economic position of the nobility was weakened. The influence of nobility was further reduced by the new law statutes

of 1864, under which their right of electing law officers was repealed. The reform of the police in 1862 limited the landowners

authority locally, and creation of all-estate Zemstvo local government did away with exclusive influence of nobility in local

self-government.

After the

October Revolution of 1917 all classes of nobility were legally abolished. Many members of the Russian nobility who fled Russia

after the Bolshevik Revolution played a significant role in the White Emigre communities that settled in Europe, in North

America, and in other parts of the world. In the 1920s and 1930s, several Russian nobility associations were established outside

Russia, including groups in France, Belgium, and the United States. In New York, the Russian Nobility Association in America

was founded in 1938. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, there has been a growing interest among Russians in the role

that the Russian nobility has played in the historical and cultural development of Russia.

The Acquisition of Nobility

There were several methods by which nobility might

be acquired. One of them was the acquisition of nobility by military service. Between 1722 and 1845 hereditary nobility was

given for long military service at officer rank, for civil service at the rank of Collegiate Assessor and with any

order of the Russian Empire. Between 1845 and 1856 nobility

was bestowed for long service at the rank of Major and State Counsellor, to all holders of the Order of Saint George and

the Order of Saint Vladimir, and with the first degrees of other orders. Between 1856 and 1900, nobility was given to

those rising to the rank of Colonel, captain of the first rank, and Actual State Counsellor. The qualification of nobility

was further restricted between 1900 and 1917 - only someone rewarded with the order of Saint Vladimir of the third

class (or higher) could become a hereditary noble.

The Privileges of the Russian Nobility

Russian nobility possessed the following privileges:

- The right of possession of populated estates (until 1861), including virtual ownership of

the serfs who worked on the estates.

- Freedom

from required military service (1762-1874; later an all-estate compulsory military service was introduced)

- Freedom from zemstvo duties (until the second half of 19th century)

- The right to enter privileged educational institutions (Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum, School

of Jurisprudence andPage Corps)

- Freedom from corporal

punishment.

- The right to have a coat of arms,

introduced by the end of the 17th century.

The Russian Nobility - The Legal Aspects

and Historical Status

Under the Imperial regime, Russia was governed primarily, if not

exclusively, by statutory law, i.e., by duly enacted laws and regulations which were incorporated in the 16 volumes of the

Complete Code of Laws of the Russian Empire. Accordingly, all matters pertaining to one's personal status were also subject

to certain statutory provisions which could be amended, supplemented or repealed not otherwise than under the rules of legislative

procedure. Under Russian Imperial law, viz. on the strength of Section 2 of the Statutes on Ranks, vol. IX, Compl. Code of

Laws, the entire population was divided into four classes:

1. Nobility;

2. Clergy;

3. Urban residents;

4. Rural residents.

The rights, privileges and duties of each of these

groups were strictly defined in the respective parts of the said Statutes. Section 15 of the latter sets forth the following

definition of the term "Nobility": The status of nobility is the consequence of the quality and virtues of those

commanders who, having distinguished themselves in ancient times by meritorious acts, and having thereby attributed to their

services the quality of distinction, conveyed to their descendants a noble rank.

Such having been the legislator's conception of nobility, it is not

surprising that the Imperial Government should have invariably protected and preserved the rights and privileges of this class.

This official attitude was most strikingly expressed in the so-called "Granting Edict" (Jalovannaya Gramota) of

Empress Catherine II of April 21, 1785* (Compl. Coll. Of Laws 16187) which not only confirmed, but substantially increased

the favors and exceptions bestowed on the nobles by virtue of the manifesto of Emperor Peter III, of February 18, 1762.

In this connection it should be noted that Empress

Catherine II paid particular attention to the consolidation of the juridical status of persons belonging to the hereditary

nobility by conferring their rank upon their children of both sexes (art. 37 Statutes on Ranks). Moreover, the daughter of

a hereditary nobleman, marrying a commoner, was not deprived of her nobility station (art. 48 same Statutes).

*All dates

are according to old style, i.e., 11 days behind in the 18th century; 12 days behind in the 19th century and 13 days in the

20th century. It is also significant that, in the way of exception of the general procedural rules, court decisions, by venture

of which persons of noble birth were to be deprived of their special privileges, could not take effect without His Majesty's

sanction (Ibidem, articles 80 and 81). At the same time Imperial legislation, seeking to prevent the possibility of the extinction

of noble, especially eminent families, as a result of the cessation of their male descendants, used to encourage the petitions

for conveying such family names to male blood relatives even in side lines.

In the Russian hereditary nobility there were families that bore titles

of princes, counts and barons. Such titles were either: (a) hereditary; or (b) granted by the Czar in recognition of exceptional

services rendered to the State; or (c) acquired by adoption of a male by a titled nobleman; or (d) by the transfer, under

a procedure provided by the law, to a noble family of a title belonging to another family related to a former by blood. Here

only the latter method of acquisition of a title (d) by hereditary nobleman shall be dealt with.

Section 79 of the Statutes on Ranks above referred to reads: A nobleman,

who has neither sons nor male relatives bearing the same family name, shall have the right to petition for the transfer of

the said family name, together with the escutcheon and title assigned thereto, to some of his male relatives, or the husband

of a female relative who prior to her marriage bore the transferor's family name. With respect to petitions of this kind the

regulations appended hereto shall be complied with.

On the strength of article 4 of the Appendix to the said section 79, only males belonging to the

hereditary nobility were entitled to submit petitions for the transfer to their family names the names and titles of other

noble families, while article 5 of the same Appendix provided that such transfers could be effected only to persons of male

sex who also belong to hereditary nobility, and not prior to their having reached full age (21 years).

The procedure of submitting such petitions was

described in article 12 of the said Appendix, which provides: The petition for the transfer of a family name shall be addressed,

during the life time of the petitioner, to His Majesty, and it shall be accompanied by the respective certificates: 1. the

effect that the person accepting the family name has given his consent thereto, and 2. to the effect that all other requisite

conditions, provided in articles 1-11 of this Appendix, have been complied with.

Article 13 of the same Appendix reads: The transfer of family names,

escutcheons and titles shall be made not otherwise than with His Majesty's consent, upon the examination of the petition therefore,

in a duly established manner, by the Department of Heraldry of the Ruling Senate, and subsequently, by the First Department

of the State Council.

Summing

up the statutory provisions above referred to, it shall be observed that under the laws of Imperial Russia, the following

were the requisite conditions for the transfer of a nobleman's family name to a person of male sex mentioned in Section 79

of Volume IX of the Complete Code:

1.

that the prospective male transferor, belonging to hereditary nobility, has no sons or male relatives bearing his name;

2. that the transferee be a male belonging to hereditary

nobility;

3. that the transferee

be of full age (21 years);

4.

that the transferee give his consent to the transfer to him of the transferor's family name;

5. that the prospective transferor's petition be addressed to His Majesty;

6. that the said petition, together with respective

certificates, be preliminarily examined and be found factually correct and valid, first, by the Department of Heraldry of

the Ruling Senate, and secondly, by the First Department of the State Council; and

7. that His Majesty give His Imperial approval of such a transfer.

Turning to the question whether in pre-revolutionary

Russia the family name of a nobleman's relative in the female line could be transferred to the said person of noble birth,

it should, in the first place, be borne in mind that even with respect to the succession of the Russian Imperial Throne the

principle excluding persons of female sex therefore was never unconditionally acknowledged or rigidly complied with.

It will be recalled that the Salic law, from which

the said discriminatory practice was derived, has framed the following rule: Of Salic land no portion shall come to a woman;

but the whole of the inheritance of the land shall come to the male sex. (Chapter LIX, paragraph 5). In Russia, however, the

following historical incident, standing in direct conflict with the above Salic dictum, may be cited. In 1730, after the death

of Emperor Peter II, male descendants of Peter the Great ceased to exist. In view of this situation his daughter Empress Elizaveta

Petrovna proclaimed her nephew Peter-Ulrich, her sister Anna Petrovna's son, the wife of Duke Charles-Friedrich of Holstein,

heir to the Russian Throne; Peter-Ulrich, assuming the name of Peter Fedorovich, married Princess Sophia-Augusta of Anhalt,

who became known as Ekaterina Alexeevna, the future Empress Catherine II. Of this marriage in 1754, a son Paul was born. Meanwhile,

in 1762, upon the death of Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, her sister's son Peter II Fedorovich ascended the Russian Throne.

And even after the enactment on April 5, 1797,

of the basic Statute on Imperial Succession, while that right was preferably granted to persons of male sex, nevertheless

on the strength of articles 27 and 30 of the Fundamental Laws, the possibility of the female line succeeding to the Throne

was specifically anticipated. At this point it may be interesting to mention the fact that in Western Europe, too, the transition

of Royal succession to female lines, because of the extinction of male descendants, is a common phenomenon, and in such cases

the Royal dynasty assumed a new name.

The

example of Great Britain is particularly characteristic, since from 1837 up to the present time, i.e., in the course of only

one century, the ruling dynasty has changed its name three times: In 1839 Victoria, the only daughter of the Duke of Kent,

the fourth son of King George III, having married Prince Albert of Saxen-Coburg-Gotha, and being the last descendant in her

line, transferred the name of her husband to her heirs, which name, however, in 1971, was changed to that of Windsor. At present,

in view of the fact that once more a woman has succeeded to the British Throne, the ruling dynasty has acquired the name of

Mountbatten after the name of Queen Elizabeth's II husband, the Duke Philip.

The example of Spain is equally noteworthy. That country, up to the revolution of

1831, was ruled by the Bourbons. Alfonso XII (1874-1885), the father of the last King Alfonso XIII (1902-1931), ascended the

Throne on the ground that his mother was the last descendant in the Hapsburg-Bourbon royal family, and thus the succession

passed into the female line.

As

regards the transfer by Russian nobles of their family names, titles and escutchcheons, same, as stated, could be effected

only by persons of the male sex. However, in the law there was no interdiction to transfer nobility family names, whether

titled or not titled, from female to male lines. As a matter of fact such transfers, of course with His Majesty's consent,

occurred quite often. The first instance of this kind took place during the reign of Peter the Great (1689-1725) when Prince

Droutzkoy-Solokinsky assumed also the name of his father-in-law Romeiko-Gourko.

By virtue of an Imperial ukaz of April 8, 1798, Senator N. I. Lodijensky was granted

the right to assume the family name and title of the Princess Ramodanovsky's, his ancestors in the female line, and to bear

and in the future hereditarily the name of Prince Ramodanovsky-Lodijensky. (Comp. Karnovich, Family Names and Titles in Russia

p. 94, St. Petersburg, 1886, in Russian).

Thus, as early as in the XVIIIth Century, the practice of substitution of one family name by another related

with the former in the female line was legally sanctioned. In the course of the XIXth and XXth Centuries such transfers were

numerous. It suffices here to cite but a few examples.

A. On June 11, 1885, by virtue of an Imperially sanctioned opinion of the State Council, Count

Felix Soumarokov-Elston was authorized to assume the name and title of his father-in-law, Prince Nikolai Borisovich Youssoupov

on condition that the combined name of Prince Youssoupov Count Soumarokov-Elston be borne exclusively by his, Felix Soumarokov's

Elston, senior male descendent.

B.

On the 29th day of April 1902, by virtue of an Imperially sanctioned opinion of the State Council Baron P. P. Mestmacher transferred

his family name and title to his nephew V. V. Budde, a Lieutenant in the Grenadier horse guard, and he was ordered hence forth

to call himself Baron Mestmacher-Budde;

C.

On June 10, 1854, by virtue of an Imperially sanctioned opinion of the State Council, Major-General Prince A. F. Golitzin

was authorized to add to his name that of his grandfather on the maternal side, Prince Prozorovsky.

D. The title of Count conferred upon the well-known

Caucasian General Evdokimov, was conveyed to his wife's niece's husband Dolivo-Dobrovolsky.

E. The Family name of Mavrin was added to that of Glinka.

F. Prince S. D. Abamelek was granted the Imperial

permission to add to his name that of his father-in-law Lazarev and to bear henceforth the name of Prince Abamelek-Lazarev.

G. Maslov received His Majesty's permission, to

add to his name the family name and title of his mother, nee Princess Odoyevsky, "in view of the extinction of the latter's

line." H. His Majesty granted the petition of N. A. Demidov for adding to his name that of Prince Lopoukhin, his grandson's

uncle in the female line.

I.

Count Shouvalov was permitted to add to his name that of Prince Woronzow, his grandfather on the maternal side.

J. On May 19, 1872, by virtue of an Imperial ukaze

the sole great grandson, by the daughter of the late Acting Privy Councilor Count Michael Speransky, the Prince Michael R.

Cantacuzene, was grated permission to add to his name and title, the title and the family name of Count Speransky and to be

called hereafter Prince Cantacuzene, Count Speransky.

Of such instances a long list could be complied. It might, however, be stated that among Russian

family names, bearing the titles of princes and counts, as recorded by the Department of Heraldry of the Ruling Senate (ed.

1914), 80 represented those to which other family names and titles, derived from female lines, were added. But even the latter

number should be increased since instances of such transfers did take place after the year 1914. Their exact number cannot

be ascertained at the present time because of the lack of authentic documentation. These lawful Imperially sanctioned changes

in the family names of the Russian nobility in pre-revolutionary Russia must be strictly distinguished from arbitrary changes,

subject to few formalities, practiced in some other countries, not excluding the United States.

France in particular is a country boasting of a large number of titles,

such as "vicomte", "prince", "duc", "marquis", etc., with no pretense of legal or

historical justification. Moreover, their bearers -a thing inconceivable in Imperial Russia - have purchased the nobility

status, as well as titles, from the Kings or even from the Popes.

The practice of usurping French titles came into vogue especially as a result of the so-called

"Great" Revolution of 1789-1799. It is known, for instance, that the real name of the ancestors of the poet Lamartine

was "Alamartine" which was later arbitrarily changed to "Lamartine", and after a while the title of "vicomte"

was added. Likewise Balzac appropriated to himself the status of nobility, and began to call himself Honore de Balzac, with

no excuse whatsoever, so that one of his biographers, Antoine Buch, justly labeled him "usurpatuer de noblesse".

Well-known British historian F. M. Thompson in his latest book, "Napoleon Bonaparte", (Oxford University Press,

New York, 1952, page 121) states that Napoleon, during his time as an Emperor (nine years), created new peerages in the amount

of 3,457 people. The new titles of nobility were distributed as follows:

31 Dukes

452 Counts

1,500

Barons

1,474 Chevaliers

Moreover, these titles "if supplanted by sufficient

income varying from 10,000 pounds for Princes and 150 pounds for a Chevalier became hereditary." Aside from that, he

created many titles of Princes, which were given mostly to the Generals for military services. Thus, Napoleon created 4,000

titles during nine years of his reign-five times more than all the Russian Emperors bestowed during 300 years of their reigns!

In comparison, in old Russia, according to the "List of Titled families and persons of the Imperial Russia" (see

the Edition of the Department of Heraldry of the Ruling Senate, St. Petersburg, 1892), there were altogether 762 titled names

of which 178 were princely names. The 762 titles belonged to persons of Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, Georgian, Tartar, Lithuanian,

and other origins).

In England,

on the other hand, peerage appears to be, in a large measure, a semi-political institution; many members thereof having been

created ad hoc. Harold Nicolson, in his book, King George The Fifth, has made the following significant admission: Queen Anne

it seemed had in 1712 created twelve new peers in order to avert opposition to the Peace of Utrecht; but that had been a very

small number and very long ago. William IV, in 1832, had, after much wriggling, promised Lord Grey to create eighty new Peers

in order to secure the passage of the Reform Bills.

And turning to more recent times, the same author posed this question: How could the King (George

V) be certain that, in yielding to Mr. Asquith's solicitations, in promising to create as many as 500 new Peers, he would

be accurately interpreting the considered wishes of the nation? These few examples demonstrate the fact that in some Western

countries the nobility status as well as titles were, and are being, acquired in a manner quite different from that which,

traditionally, prevailed in pre-revolutionary Russia, where these matters were subject to scrupulous legislative provisions

and most formal procedure. This is the reason why in Russia, with her population of almost 200,000,000, the number of titled

families, in the way of percentage, was the smallest of any other country.

It now remains to review briefly the present-day legal status of the Russian nobles

residing outside of the Russia, and the method in which they may effect transfers to their names those of related families,

whether in male or female lines. The Provisional Government, which succeeded the Imperial Government, did not change the laws

of the Russian Empire concerning the rights of personal and hereditary noblemen to family names, titles and escutcheons. After

the coup d'йtat of February 27, 1917, the Provisional Government, by virtue of its decree of May 13, 1917, granted the

power of ratifying the escutcheons of private persons, which was formerly vested in the Emperor, to the Department of Heraldry

of the Ruling Senate, which body did actually approve sixty escutcheons pursuant to petitions filed prior to the revolution.

Among such escutcheons was one of the titled family of the Count Dmitriev-Manonov.

As a result of the Communist revolution some 4,000,000 people, mostly

belonging to the educated classes, were swept out of Russia. The bulk of these refugees eventually settled in Western Europe

and in America. Meanwhile by the decree of the Central Executive Committee of the Workers' and Peasants' Government of November

12, 1917 (Coll. En. 1917, No. 3, Sect. 31) all ranks and titles were abolished in Russia and by the decrees of the Soviet

of People's Commissars of November 24, 1917 (Coll. En. 1917, No. 4, Sect. 50) and of December 14, 1917, No. 9, Sect. 123)

the Ruling Senate and the State Council, respectively, were abolished.

The aforementioned Soviet decrees have not, and cannot have, an extra-territorial

effect, and those Russians who have left Russia and refuse to submit to the Soviet Government are not, and cannot be, bound

by whatever legislation that Government chooses to enact. In particular, the Russian йmigrйs may well disregard

the Soviet decree of November 13, 1917, abolishing all ranks and titles.

Hence, there arises the question in what manner the Russians of noble descent, residing

outside the Russia, can exercise the rights, which they enjoyed under the provisions of Sect. 79 of Vol. IX of the Code of

Laws of the Russian Empire. In our opinion the method and procedure of the transfer of Russian family names should follow

as closely as possible the statutory provisions thereon contained in the said Code of Laws.

Inasmuch as both the Ruling Senate, with its Department of Heraldry,

and the State Council are non-existent, their functions in connection with the verification of the applications for the transfer

of family names, titles and escutcheons should be assumed by the Genealogical Committee of the Russian Nobility Association

in France or in the United States, and if the claims of the applicants therefore should be found factually correct and valid,

such applications should then be submitted for approval to the living Head of the Russian Imperial House, being Her Imperial

Highness The Grand Duchess Maria Wladimirovna of Russia, de jure Empress Maria I of All The Russias, Head of The Imperial

House and Family of Holy Russia.

The Princes of The Russian Empire

The list of

the Russian princely families that were still extant in 1700:

Riurikovichi

- from the House of Chernigov:

- Odoevsky

- Massalski

- Eletsky

- Bariatinsky

- Obolenski

- Repnin

- Dolgorukov

- Shcherbatov

- Myshetsky

- Oginski

- Volkonsky

- Gorchakov

- from

the House of Galicia:

- Drutskoy-Sokolinsky

- Drucki-Lubecki

- Babichev

- Putyatin

- from

the House of Smolensk:

- Vyazemsky

- Kozlovsky

- Korkodinov

- Dashkov

- Kropotkin

- from the House of Yaroslavl:

- Prozorovsky

- Shakhovskoy

- Khvorostinin

- Lvov

- Zasekin

- Troekurov

- Dulov

- from

the House of Rostov-Beloozero:

- Lobanov-Rostovsky

- Kasatkin-Rostovsky

- Shchepin-Rostovsky

- Beloselsky-Belozersky

- Sheleshpansky

- Ukhtomsky

- Vadbolsky

- from the House of Starodub:

- Romodanovsky

- Gundorov

- Gagarin

- Khilkov

Gediminovichi

- Golitsyn

- Kurakin

- Khovansky

- Trubetskoy

- Woroniecki

- Nieswicki

- Volynsky

The Eastern Princes

- Sibirsky

- Cherkassky

- Meshchersky

- Engalychev

- Yusupov

- Urusov

- Kudashev

- Kugushev

- Tenishev

- Dondukov,

etc.

In 1801, the Russian

Emperor recognized a lot of princely families from Georgia. These include: Bagration, Gruzinsky, Imeretinsky, Mukhransky,

Dadianov, Gurielov, Abamelik, Abashidze, Abkhazov, Agiashvili, Amilakhvarov, Amirejibov, Andronikov, Argutinsky, Avalov, Babadyshev,

Baratov, Bebutov, Begtabegov, Chavchavadze, Chelokaev, Cherkezov, Chkheidze, Cholokov, Dadeshkeliani, Davidov, Diasamidze,

Djandierov, Djaparidze, Djavakhov, Djordjadze, Eristavov, Gelovani, Guramov, Gurgenidze, Iashvili, Karalov, Kobulov, Lionidze,

Machabeli, Magalov, Makaev, Mikeladze, Orbeliani, Palavandov, Pavlenov, Ratiev, Rusiev, Saginov, Shalikov, Shervashidze, Sumbatov,

Tarkhanov, Tsertelov, Tsitsianov, Tsulukidze, Tumanov, Vachnadze, Vakhvakhov, Vizirov, Zurabov. The following families obtained

their princely titles from the Emperors of Russia after 1700:

30.5.1707 Menshikov31.7.1711

Kantemir5.4.1797 Bezborodko19.1.1799 Lopukhin8.8.1799

Suvorov29.7.1812 Kutuzov30.8.1814 Saltykov30.8.1815

Barclay de Tolly22.8.1826 Lieven4.9.1831 Paskevich6.12.1831

Kochubey8.11.1832 Osten-Sacken1.1.1839 Vassiltchikov16.4.1841

Tchernyshov10.11.1843 Czetwertynski6.4.1845 Voronzov25.6.1847

Giray21.12.1849 Tarkovsky23.2.1853 Chingiz18.12.1852

Romanovsky26.8.1856 Orlov18.4.1861 Swiatopolk-Mirski19.1.1865 Cantacouzene4.1.1867 Mingrelsky26.6.1875 Mavrocordato5.12.1880

Yurievsky31.3.1884 Sturdza14.8.1886 Persidsky23.11.1892

Dabizha9.6.1893 Muruzi11.8.1896 Gantimurov15.8.1915

Paley

The Counts of the Russian Empire

1706

Sheremetev20.4.1707 Golovkin23.2.1710 Apraxin8.7.1710

Zotov18.2.1721 Bruce7.2.1722 Apraxin II7.5.1724

Tolstoy24.10.1726 De Vieira24.10.1726 Lowenwolde5.1.1727

Skavronsky24.2.1728 Munnich3.1730 Saltykov28.4.1730

Ostermann19.1.1731 Jaguszinski19.1.1732 Saltykov II13.8.1740

Lacy29.3.1740 Bruce II25.4.1742 Efimowski25.4.1742

Hendrikov25.4.1742 Tchernyshov25.4.1742 Bestuzhev16.4.1744

Razumovsky15.7.1744 Ushakov15.7.1744 Rumyantsev5.9.1746

Shuvalov17.2.1760 Buturlin22.9.1762 Orlov22.9.1767

Panin10.7.1775 Potemkin25.9.1789 Suvorov30.10.1790

Saltykov III6.5.1793 Krechetnikov1.1.1795 Fersen1.1.1795

Potemkin II12.11.1796 Bobrinskoy5.4.1797 Voronzov5.4.1797

Bezborodko5.4.1797 Dmitriev-Mamonov5.4.1797 Zavadovsky5.4.1797

Buxhoeveden5.4.1797 Kamensky5.4.1797 Kakhovsky5.4.1797

Gudovich5.4.1797 Mussin-Pushkin9.6.1797 Osten-Sacken8.4.1798

Sievers21.4.1798 Stroganov22.2.1799 Lieven22.2.1799

Pahlen22.2.1799 Kushelev22.2.1799 Rostopchin4.4.1799

Denisov4.4.1799 Kochubey5.5.1799 Arakcheev5.5.1799

Kutaisov15.9.1801 Vasiliev15.9.1801 Tatishchev15.9.1801

Protasov12.12.1809 Gudovich II29.10.1811 Kutuzov29.10.1812

Platov2.5.1813 Miloradovich29.12.1813 Barclay de Tolly29.12.1813 Bennigsen30.8.1816 Tormasov1.7.1817 Lambsdorff19.4.1818

Vyazmitinov12.12.1819 Konovnitsin12.12.1819 Guriev8.4.1821

Osten-Sacken II25.12.1825 Orlov II22.8.1826 Tatishchev II22.8.1826

Tchernyshov II22.8.1826 Kuruta22.8.1826 Pozzo di Borgo22.8.1826 Stroganov25.6.1827 Diebitsch15.3.1828 Paskevich9.6.1829

Tohl1.6.1829 Oppermann22.9.1829 Kankrin6.12.1831

Vassiltchikov8.11.1832 Golenishchev-Kutuzov8.11.1832 Benckendorff1.7.1833

Essen1.7.1833 Levashov25.6.1834 Mordvinov1.7.1835

Novosiltsev1.1.1839 Speransky26.3.1839 Kiselev26.3.1839

Kleinmichel18.4.1842 Bludov19.3.1843 Kossakowski24.12.1843

Przezdiecki1.7.1846 Uvarov1.7.1846 Baranov1.7.1847

Adlerberg19.9.1847 Nikitin2.10.1847 Rudiger3.4.1850

Vronchenko3.4.1850 Perovsky26.8.1852 Muravyov26.8.1856

Berg26.8.1856 Olsufiev26.8.1856 Grabbe26.8.1856

Zakrevsky26.8.1856 Sumarokov26.8.1856 Putyatin20.11.1856

Perovsky II17.4.1859 Evdokimov23.4.1861 Rostovtsev23.4.1861

Lanskoy27.5.1862 Luders17.4.1865 Muravyov II28.10.1866

Lutke18.3.1871 Brunnow1.1.1872 Korff19.3.1873

Miloradovich II29.4.1874 Kotzebue12.12.1877 Ignatiev17.4.1878

Loris-Melikov20.8.1878 Milyutin19.2.1880 Valuiev9.2.1881

Baranzov23.11.1883 Delyanov21.3.1884 Belyovskoy-Zhukovsky20.1.1890 Reutern21.2.1896 Simonich1.1.1902 Solsky18.9.1905

Witte1912 Dmitriev-Mamonov II18.11.1913 Freedericksz29.1.1914

KokovtsevIII.1915 Brasov